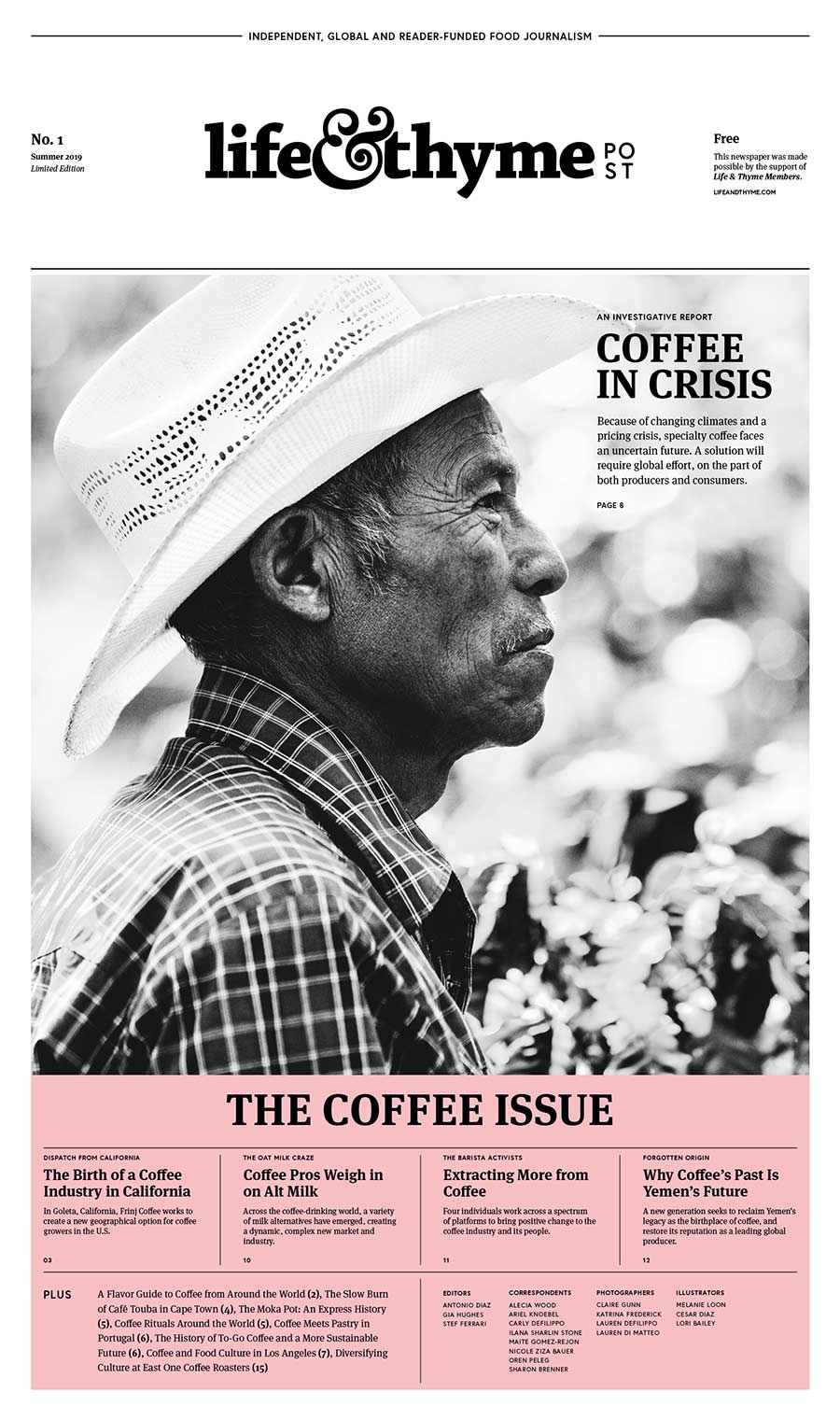

This story can also be found in our inaugural issue of Life & Thyme Post, our limited edition newspaper for Life & Thyme members.

July 24, 2019

Words by Oren Peleg

Photography by Lauren di Matteo

It is late March in Guatemala’s northwestern province of Huehuetenango. The region is mountainous with the sharp peaks of the Sierra Madre de Chiapas cutting through, and mostly arid despite its tropical latitude. Along the Cuilco River valley, dusty oaks and dry shrubs cover the slopes above, edging off patches of dark green coffee trees and the sporadic farmhouse. The dry season has yet to break this year, and the rains have not returned since October.

This persistent lack of rain—one of the most evident symptoms of climate change in the province—has added Huehuetenango to a growing area of land called the Dry Corridor, which snakes up through Panama and into southern Mexico, and which is home to some ten million people who mainly subsist on agriculture.

The United Nations has designated the Dry Corridor as one of the most susceptible regions in the world to the effects of climate change. The area regularly experiences long periods of decreased precipitation—up to forty percent below average—coupled with heatwaves. During other periods, such as El Niño, tropical storms devastate the region with flooding that collapses hillsides, erodes valuable topsoil, and overflows rivers.

Along the side of a two-lane highway about an hour west of Huehuetenango’s largest city, a caravan of trucks park. The predawn chill quickly gives way to the heat of the sun as a team from Chameleon Cold Brew and a few representatives of Anacafé (the Guatemalan national coffee association) set across a wobbly rope-bridge to visit an eight-hectare coffee farm owned by the Sales family.

The coffee grown in Huehuetenango is some of the most sought after coffee in Central America, and the flavor profile matches Chameleon’s specific needs. However, the effects of climate change and the deepening crisis in coffee pricing have left small farms like this one struggling to survive, and with limited resources to cope.

“The problem is sometimes the rains are not coming,” Efrain Sales Geronimo, one of the three Sales brothers who run this farm, tells his visitors. “We have to think about irrigation to help the plants until the rains come.” An irrigation system, one of the most expensive investments these small farmers can make for their land, is part of the potential assistance Chameleon is looking to bring through their partnership with Anacafé.

As we walk up the slope of the Saleses’ plantation, I ask Matt Swenson, Vice President of Coffee and Sustainability for Chameleon, what he looks for on these site tours. “I look at the health of the plants,” he begins. “Ultimately, you’re looking for keys to good practices.”

In 2016, when Swenson joined Chameleon, he knew keeping the company’s supply chain stable meant investing in the farmers and their communities. Since Chameleon sources more coffee from Guatemala than anywhere else in the world, it also meant their biggest investment would be here. “It took us two years to get up and going because we couldn’t find institutional-scale partners we were happy with who we felt could execute the mission,” Swenson says. Upon learning of the infrastructure Anacafé has been building out over the last five decades to help farmers across Guatemala, Chameleon knew it had found its partner.

This day’s farm visit is part of a larger tour of Chameleon’s supply chain in Guatemala, and allows the team to find out from the farmers exactly what they need to continue growing quality coffee and maintain their livelihood. While it’s clear climate change is a major pressure on these farmers and their crops, the solutions are less clear.

It’s this connection between coffee and climate change that James Rising thinks about most. An assistant professor at the London School of Economics’ Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, Rising predicts “there’s going to be a pretty significant shift in where coffee is going to be economically productive across the world. You’re going to see a lot of farmers who historically have been able to have productive or high-quality farms who just aren’t going to be able to do that in another ten or twenty years.”

“They have a startling study out there that says by 2050 global demand for coffee will double, and by 2050 the suitable lands to grow coffee will be reduced by fifty percent,” Swenson says. “That’s simple math; it doesn’t add up.” Long-term adaptation for these coffee farmers may require them to move to higher elevations where cool temperatures remain, but less land is to be found.

In addition to changing weather patterns and reducing the amount of land suitable for coffee’s specific growing requirements, global warming has increased the vulnerability of coffee plants to a host of diseases and pests—primarily coffee leaf rust (a disease caused by the fungus hemileia vastatrix) and the coffee berry borer beetle (also known as broca). Increasing global temperatures have spread the reach of these diseases to areas that were previously too cold.

Beginning in the 2011-2012 harvest season, an outbreak of rust devastated coffee production throughout Central America. The spread of the disease was attributed to climate change, but since eighty percent of coffee producers here are small holders with virtually no resources, the effects were catastrophic. Farmers attempted to grow other crops—corn, potatoes, beans—to generate some replacement income, but drought and rising temperatures left these new crops to fare no better. According to World Coffee Research, by the 2017 season, seventy percent of Central America’s coffee farms were affected with rust, as some countries saw fifty percent of their coffee acreage lost to the disease. The damages from the epidemic totaled $3.2 billion, and lead to 1.7 million workers losing their jobs—many of whom never returned to the farms, forced instead to migrate to other cities or countries for work.

“The current crisis is making it an untenable situation for folks who depended on coffee for their livelihood, and they can no longer do so,” Ric Rhinehart, executive director emeritus of the Specialty Coffee Association, begins. Farming families across Central America are either being separated as they look for new opportunities, or are leaving together for urban centers and countries like the U.S. and Mexico. “That is a real and pressing issue and it’s rising to the level of a substantial humanitarian crisis.”

According to the New Yorker, the United States and Mexico deported ninety-four thousand Guatemalans in 2018, with over half of them coming from Guatemala’s drought-plagued western highlands. As our caravan passes along a backroad returning to Huehuetenango’s provincial capital, our translator points out a large, white house distinct from those around it. We notice more as we continue, some with beautiful blue-tiled roofs, others with a wall encircling them. These homes are paid for by family members who have migrated (likely to the U.S.) and send back remittances to those who stayed, our translator explains. “They don’t have to work anymore,” he continues of those in the white houses. “They get more money than they would make working on a farm.”

Migration has also affected the local schools. Rafael Rafael, a teacher in a small village in Huehuetenango, told the New Yorker that at least five students per term drop out of his twenty-five-student class to migrate with their family. “I don’t like it, but it’s hard to blame them.”

Huehuetenango, like much of western Honduras and El Salvador, has seen average yearly rainfall drop from 165 inches in 1991 to under 110 inches in 2015, while the average temperature has gone up 5ºF over the same period. A recent report by the Kew Royal Botanical Gardens shows a similar change in Ethiopia. The report finds that the country’s average temperature has gone up about half-a-degree Farenheit per decade since 1960, and rains have decreased by fifteen to twenty percent since the mid-1970s. “Coffee is being pushed to the top of the mountain,” Wondyifraw Tefera, an Ethiopian coffee expert tells NPR. But the new coffee-growing lands don’t fully make-up for the lands that are disappearing. Meanwhile, in countries like Peru and Colombia, climate change has increased rainfall in ways that are hurting coffee production.

In 2018, Chameleon began its first community-driven sustainability project in the St. Ignacio region of Peru, where climate change was causing abundant, if unpredictable, bouts of rain. “The coffee is dried in the sun,” Swenson says of the Peruvian farms. Unexpected rainstorms, which can appear within minutes, damage coffee left out to dry, and ruin its quality. “Instead of getting that twenty-cents-a-pound, high-quality premium, [farmers] go the commercial way” for a lower price. The company invested in covers for the farmers’ drying beds, and built a quality grading lab so the community could analyze which improvements were resulting in better quality. A similar project is underway in Tolima, Colombia, with mechanical drying machines.

Back in Guatemala, the Chameleon team visits one of Anacafé’s CERCAFE farms. These rural training centers act as a model for the surrounding communities to demonstrate the best practices Anacafé has developed for coffee farming in each region.

According to Arlam Aguirre, Anacafé’s lead field technician for Huehuetenango, the integration of shade trees and soil barriers has been Anacafé’s main focus in this region. The large fruit trees he is introducing to the coffee farms “help for shade, but also, we want to have profits for the producers while they’re not receiving anything from coffee,” Aguirre explains. “They can sell avocados; they can sell lemons or bananas.”

In its report on Ethiopia, Kew Gardens outlines four main intervention methods for coffee farmers to counter climate change: implementing irrigation systems, tree shade management, terracing land for soil conservation, and mulching—which, according to the report, “not only helps to preserve soil moisture and decrease soil temperature (reducing evapotranspiration), but it can also increase soil fertility, suppress weeds, and improve rainfall penetration into the ground.”

As for where the resources for such improvements should come from, and who should manage them, the report advises that “a coffee governing body should be formed, with the remit of ensuring advocacy and effective governance for coffee sustainability and resilience.”

Chameleon is a proponent of such industry-wide collaborations, and contributes to the World Coffee Research fund alongside large corporations like Starbucks, all the way down to small-scale, specialty roasters. “We can all contribute to this fund to allow the PhDs in coffee and the agronomists who are experts in those fields to do long-term research to battle this,” Swenson says.

A few months after the site visits in Guatemala, I asked Chameleon if any results have come in from the sustainability project in Peru. The covered drying beds and quality lab have already led to a thirty-seven percent growth in high-quality coffee. “That equates to a quarter-million pounds of newly generated specialty coffee out of that lab in year-one,” Swenson says. “To put that in perspective, that’s a hundred-percent increase of our total volume that we’re buying out of that little micro-region.”

“One of the reasons we’re not screaming from the rooftops is because we just have one year of data,” Chris Campbell, Co-Founder of Chameleon Cold-Brew, concludes, meaning the results may swing over the coming years. But the results thus far are encouraging, “so long as you accept the premise that there will be a market for quality over the long haul, and that the market will pay better than commodity prices.”

The sobering reality of the current situation is the countries who consume the most coffee are also the ones who have contributed most to climate change. But the path to large-scale, equitable solutions is not an impossible one; in fact, it’s the only path to sustain coffee in the long-term. Chameleon’s efforts to stabilize the communities of their growers and bring much-needed assistance to them represent what is hopefully an awakening by the wider industry.

Meanwhile, the continued boom of the specialty coffee scene has empowered consumers to educate themselves on where their coffee is from, who is growing it, and what the impact of their decisions is. Ultimately, systemic change won’t be achieved through the efforts of individual players, but through the collaboration of consumers, governments, and the entire coffee industry.

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.