This story is published in partnership with KCET / PBS SoCal.

Sake has existed for thousands of years, first appearing in texts as far back as the third century. The wine has long been used in spiritual Shinto or Buddhist ceremonies and enjoyed at the Imperial Court. One ancient origin story says that young virginal maidens, gathered at shrines, would chew and spit rice kernels into water, the enzymes in their saliva kick-starting the molecular conversion needed to transform the grain into alcohol. Sake has evolved over the centuries, brewer’s secrets passing through the skilled hands of monks and government-appointed masters, to arrive at our table in myriad forms of deliciousness — both modern and traditional. With a rich history and seemingly endless varieties and styles, it’s a shame many oversimplify sake on a menu, corralling it into just two categories: “hot” or “cold.”

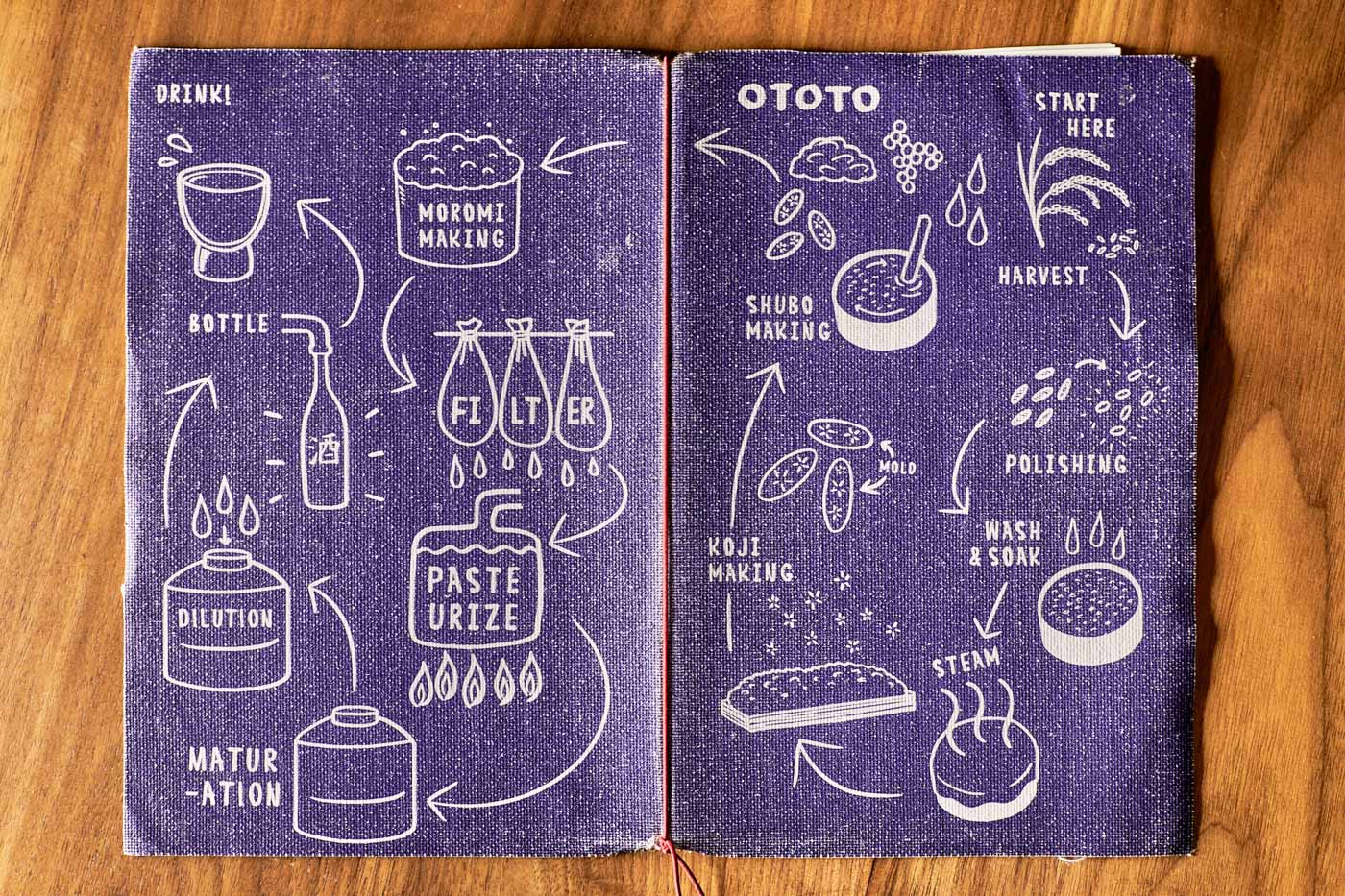

To help introduce and better understand this storied beverage, we turn to Courtney Kaplan, sommelier, sake aficionado and co-owner of restaurants Tsubaki and Ototo in Los Angeles. Kaplan has been quietly revolutionizing the way Angelenos drink sake, making the dauntingly wide world of rice wine fun and approachable.

When first educating staff, Kaplan starts with a basic explanation of the sake brewing process. At their simplest, the steps for creating sake unfold as follows: Take whole, brown rice. Polish the grains to expose the starchy interior. Wash, soak and steam the rice and add koji mold. Make a starter with that koji rice, water, yeast and more steamed rice. Mix the starter with even more rice. Let it ferment into alcohol. Then, filter, pasteurize, dilute and age.

Let’s break down a few of these elements and processes to identify the nuances and techniques that make sake production — and the brewer’s choices along the way — unique.

Rice

Among around the 100 varieties of rice cultivated for sake making, Kaplan identifies the three most commonly used as Yamada Nishiki, Gohyakumangoku and Omachi.

Yamada Nishiki: This is the “king” of sake rice and is the most commonly grown in Japan. Yamada Nishiki special varietal forms the base for many of Japan’s most prized sakes. Although widely farmed, Yamada Nishiki from certain prestigious regions are highly coveted, especially from the grain’s region of origin — Hyōgo Prefecture. Kaplan notes, “it’s a pretty flamboyant style of rice. It makes a fruity, flavor-forward, personality-filled, style of sake.”

Gohyakumangoku: Gohyakumangoku hails from the Niigata Prefecture in Japan, where sake tends to lean light and dry. Kaplan calls gohyakumangoku a “clean, precise, quieter rice,” producing styles that may not be as flashy as their counterparts.

Omachi: Native to the Okayama Prefecture, Omachi is the oldest known variety of heirloom sake rice. Kaplan explains that for a long time, growers preferred not to work with Omachi due to the grass’ height, which can reach up to four feet. A lot of precious product would be lost to the wind. However, Kaplan has noticed an increase in popularity, with brewers proudly mentioning the varietal on the bottle. Omachi contributes to more earthy, herbaceous and savory styles of sake.

Rice Polishing

One of the most important steps on the road to sake making, rice polishing, greatly affects the final outcome in texture, flavor and style. The whole brown rice is milled to remove the layers of outer proteins and fat, revealing its starchy heart. The percentage of rice grain remaining after milling determines the style of sake, with legal polishing requirements to acquire certain labelings (more on this later!).

Water

According to Kaplan, water is one of the most talked about elements when it comes to pride in sake-making, with entire pages of brewery websites devoted to proclaiming the cleanliness and notoriety of their water source. In mountainous regions, breweries often use snowmelt, runoff from famous mountains like Mount Fuji. Kyoto boasts of incredible soft water, pulled from underground. Much of the final beverage is water, which is added along the entire process and used in dilution at the end, therefore extraordinary attention is attached to its origin.

Koji

Rice by itself does not contain fermentable sugars. In comes koji. Scientifically named aspergillus oryzae, koji fungus converts rice starch into simple sugar molecules. The yellow koji used for sake is also responsible for other fermented, umami-intense foods like soy sauce and miso. Once the sake rice is washed, soaked and steamed, a portion of the rice is separated into the koji room, the most precious space in the brewery and often the domain of the most skilled brewmaster. In this temperature- and humidity-controlled room, mold spores are gently added to the rice and closely monitored for growth over the course of a few days. On completion, the rice tastes very sweet.

Yeast

Kaplan explains that very few breweries in Japan will use native yeast, preferring a controlled approach. Most breweries acquire yeast from the Brewing Society of Japan, which isolates and propagates commercial yeast from a wide variety of locations, from famously delicious breweries to exceptional house yeasts. As such, sakes don’t express terroir in the way other alcoholic beverages might.

Shubo

Yet another important step in the process that helps determine what’s in the bottle. There are three main brewing methods still in use today that center around the making of shubo, which is essentially the sake starter batch.

Kimoto: This old-fashioned brewing technique dates back to the 1600s and relies on a very labor-intensive strategy to break down the rice and develop the lactic acid needed to create the ideal environment for fermentation. Brewers place rice, water, and rice that’s been acted on by koji into small tubs. Using poles, two brewers alternate ramming the mixture, methodically breaking up the grain and encouraging the formation of lactic acid which helps prevent spoilage. While the old-school methods can have “earthy, smoky, sometimes practically gamey aromas and flavors,” says Kaplan, kimoto tends to exhibit “creamier, rice-ier” qualities.

Yamahai: The successor to kimoto, the yamahai method was first developed in 1909 when the Suehiro Sake Brewery realized they could warm up the shubo and the rice mixture would dissolve and form lactic acid on its own, eliminating the need for all that exhausting pole ramming. “Another word for kimoto is yama-oroshi,” says Kaplan. “Yamahai means quitting yama-oroshi. It takes longer time-wise, but it’s a lot less labor.” Because the technique requires a longer waiting period for the starter to form — about two weeks — more natural processes can occur such as the introduction of ambient yeasts and bacteria. Because of this, yamahai skews wilder and more acidic, displaying mushroom, toasted nut and savory flavors.

Sokujo: Sokujo is the modern standard for sake, a quick method that relies on commercial lactic acid. The acidic environment protects the brew immediately and there is less opportunity for off-flavors. Because this method offers the most control, sokujo flavor can run the gamut. Unless kimoto or yamahai are on the label, the sake most likely uses this technique.

Moromi

Moromi is the fermenting mash that combines the shubo, rice, koji rice and water. Kaplan notes sake is “the only beverage in the world that is made with multiple parallel fermentations.” As koji continues to grow within the tank, turning more rice into sugar, yeast multiplies and turns that sugar into alcohol.

Maturation

After filtration and pasteurization often comes a short aging period. Generally, the sake sits in a neutral non-porous tank or bottle to settle for a few months, although the length of time varies. Some recommend their sake is drunk immediately, straight from the tank. Kaplan says one woman brewer ages her sake for four years prior to release. Before modern materials, sake was sometimes aged in cedar casks, although not many breweries adopt this pungent, distinctive approach (if looking for it, it’s called Taru Sake).

___

Here comes the fun part — drinking! To guide you along your journey, here are some major categories you might encounter in your local restaurant or bottle shop, along with suggested pairings from Kaplan.

Junmai

The word junmai translates to “pure rice” and is used to identify sakes made solely with rice, water and koji. “Junmai is sort of telling you what it isn’t,” says Kaplan, as the omission of this word points to being a honjozo. There are no legal rice polishing requirements for junmai, but they typically run around 60% to 70% (where the percentage is how much rice is left after milling). Junmai can express a wide range of flavors, but tend to be umami rich, textured, earthy and not heavily fruity or floral.

Pairing: Junmai are super versatile, but goes well with meat and fish coming off the grill, as well as dishes with a lot of dashi. Kaplan suggests for a Western twist, try with roasted chicken or turkey.

Honjozo

Honjozo refers to sake with a small amount of neutral spirit added to help bring out aromatics and flavor. “During [World War II], all sake was required to be honjozo because there were rice shortages and most rice had to be earmarked for feeding the population,” explains Kaplan. “They would use honjozo to stretch the rice that they had.” While it can have the reputation of being the inferior, “unpure” version of sake, Kaplan attests to its quality (and excellent value). Honjozo usually tastes lighter and more aromatic than their un-spiked junmai cousins.

Pairing: Drink honjozo to cut through the fat in fried, crispy foods. At Tsubaki, order the tempura.

Ginjo

Ginjo sakes have a minimum polishing requirement of 60%. All that milling produces a very aromatic, fruity, floral beverage. For the sake novice, Kaplan suggests the ginjo category, a crowd pleaser with its soft, clean finish. One can have either a junmai ginjo or a honjozo ginjo depending on whether alcohol is added prior to filtering, although a honjozo will never call itself out.

Pairing: Ginjo sakes are wonderful when paired with lighter foods like dressed springtime vegetables or sashimi.

Daiginjo

This translates to “big ginjo,” because these super refined sakes have a minimum polishing requirement of 50%, with breweries going as low as 1% (again, this is the amount of rice core left over — that’s basically a grain of sand!). This expensive category tends to be luxuriously flavored, very perfumed, with a velvety texture. Their elegant aromatics make for a great sipping experience alone, as an aperitif, or between courses.

Pairing: Delicately seasoned dishes, like white fish or Kaiseki cuisine. Or alone, for a special occasion.

Namazake

Most sake goes through two rounds of pasteurization. The word nama in Japanese means “raw” or “alive,” and in this context indicates one step of pasteurization has been skipped. Nama nama skips both. According to Kaplan, not only does pasteurization kill yeast and bacteria, it serves to soften acidity and mellow aromatics. In unpasteurized sake “the aromatics are turned up, the acidity is turned up, it has this vibrancy to it. It has a more electric feel,” she says. “Sometimes it will even have a bit of spritz depending on the brewers.” Some old-school sake makers snub nama, feeling its flashiness doesn’t harmonize with food, although the style has newfound popularity among the younger generation — especially with natural wine drinkers.

Pairing: Pizza, tacos and spicy Thai food.

Nigori

Kaplan explains nigori sake often gets mistranslated as “unfiltered.” In fact meaning “cloudy,” this milky-looking beverage is coarsely filtered, leaving more rice particles behind. Those unfermented rice solids contribute to nigori falling on the richer, sweeter side of the spectrum. Texturally trickier to pair with food, Kaplan enjoys experimenting with nigori in cocktails or in desserts like nigori popsicles. She also suggests looking for the lighter usu nigori, which is more hazy than cloudy.

Pairing: Counterbalance the sweetness of nigori with hot, spicy food.

___

Sake can be served at a wide range of temperatures depending on its style. Namas are always presented cold, directly from the fridge. Ginjos also tend to prefer a cooler climate. Warming can burn off some of the lighter, more aromatic compounds, so can therefore emphasize the textural, umami flavors of a junmai. “I think of it almost like a broth, like chicken stock,” says Kaplan. “Drinking that warm enhances the flavor. It unlocks this savory richness.” In general, temperature should max out around 100 to 120 degrees. With that being said, a lot of enjoying sake is experimenting, throwing out the rulebook. There are exceptions, and renegade brewers abound.

It’s poor form in Japanese culture to pour your own sake, so grab a bottle and a friend, serve each other an ochoko full, and toast to tasty, newfound knowledge.

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.