My life revolves around food. The more I consume it, the more it consumes me. I live for my next meal; I dream about things to cook. I turn to the recipes section of the weekend paper before reading anything else. Recipe books tumble from my shelves, cuttings spill from folders and my Instagram feed, Pinterest and bookmarks are pretty much all about food.

Food is the absolute stuff of life; it is the foundation of our relationships and is one of the essential, elemental things that every living creature in the world has in common.

Today, more than ever before, food is everywhere. It is the fashion of the moment and it seems the trend is here to stay, but with such a proliferation of foodie content, it can be overwhelming. While I love to discover new recipes, chefs and ideas, what gives me the greatest thrill of all is to hunker down and read a cookery book. Not just to skim through the pictures and recipes, or to look for some inspiration for dinner, but actually to read it as a piece of literature, a work of art.

This is where we start to sort the wheat from the chaff; good food writing is about so much more than just an ingredients list and a method. The very best should take us on a journey and tell a story, dragging us by our senses into other kitchens, other countries and other worlds. Books and blogs are ten a penny, but truly great food writers are worth their weight in caviar.

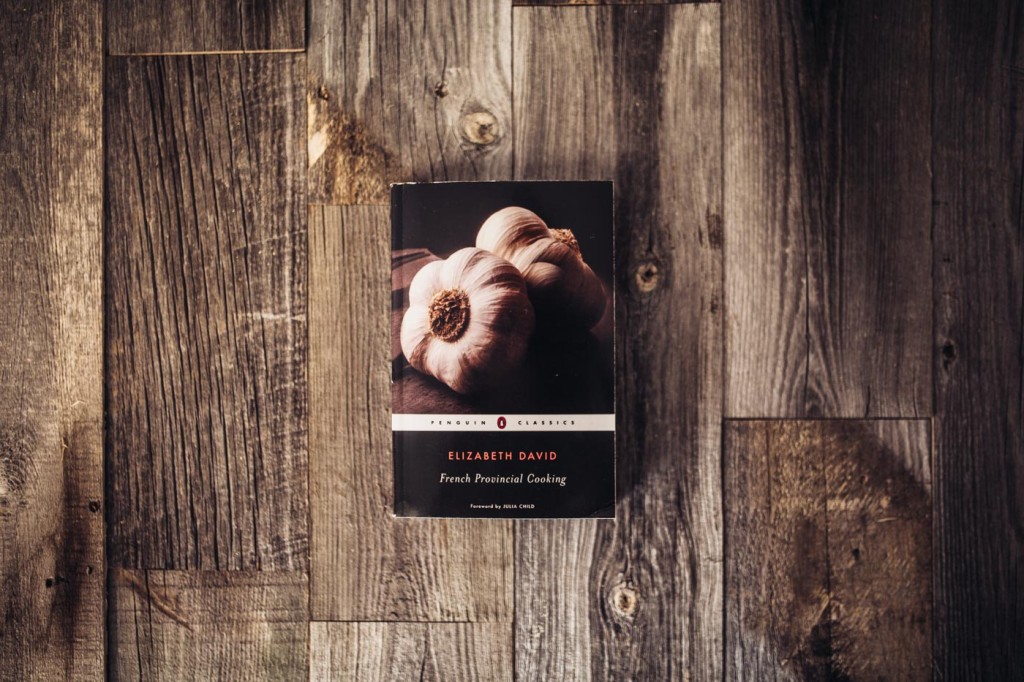

For me, as for so many others, it started with Elizabeth David. I’m not a first generation reader, but I grew up eating her food and hers were some of the first recipes I cooked myself. As my tastes began to develop, it was David who led me into the kitchen. Her writing is authoritative, her instructions matter-of-fact even, but she makes me want to cook. She brought the Mediterranean sun into the kitchens of grey, post-war England and each time I open her books, my kitchen is suffused with that same warm glow, the light still undimmed all these years on. Where today’s books have a photograph to accompany every recipe, hers had none. A picture may be worth a thousand words, but it was through her inimitable narrative alone that David brought to life the scents and colors of a dish, painting for her readers the greatest sensory picture of all. Her description of a market in France transport us to the heart of the scene better than any photograph possibly could:

“At dawn they will be unloading their melons and asparagus, their strawberries and redcurrants and cherries, their apricots and peaches and pears and plums, their green almonds, beans, lettuces, shining new white onions, new potatoes, vast bunches of garlic. By six o’clock the ground will be covered with cageots, the chip vegetable and fruit baskets, making a sea of soft colours and shadowy shapes in the dawn light. The air of the Place is filled with the musky scent of these little early Cavaillon melons, and then you become aware of another powerfully conflicting smell – rich, clove-like, spicy. It is the scent of sweet basil, and it is coming from the far end of the market where a solitary wrinkled old man sits on an upturned basket, scores and scores of basil plants ringed all around him like a protective hedge.”

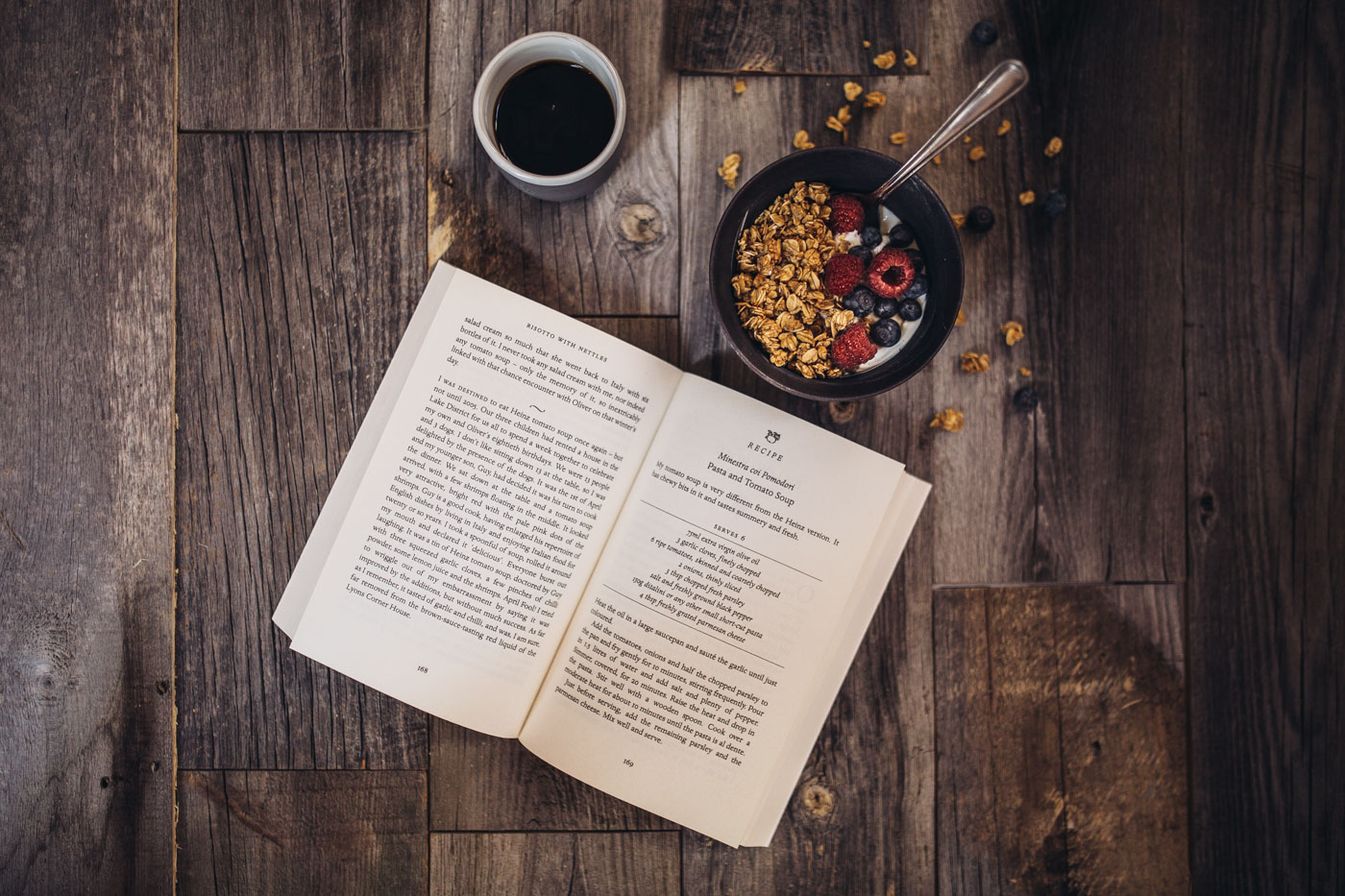

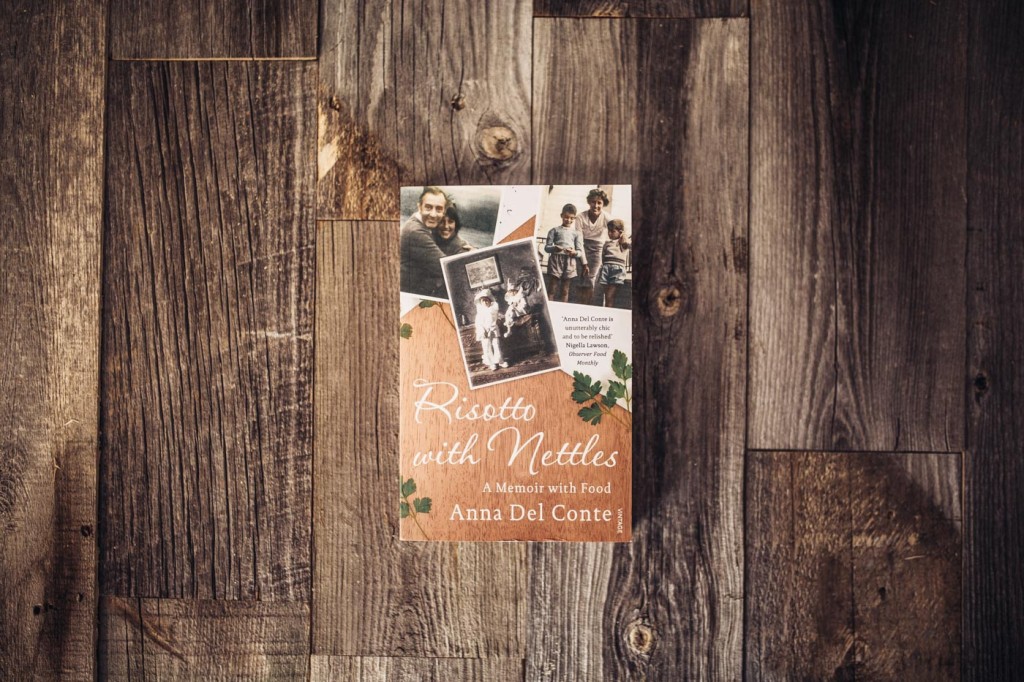

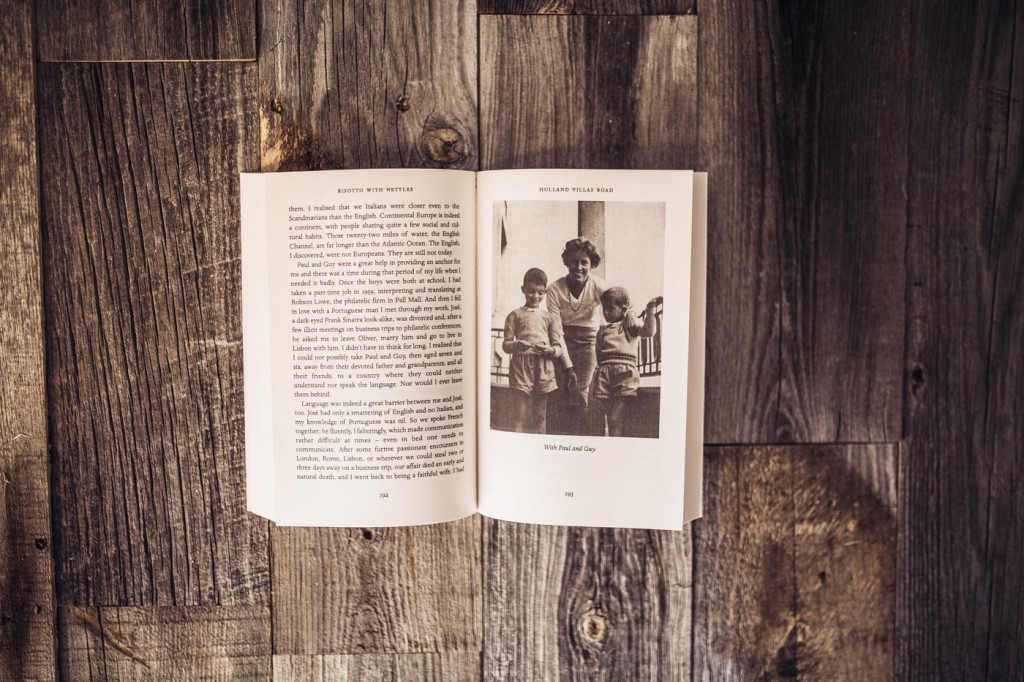

From the same era comes the Anna Del Conte, instrumental in bringing Italian food to Britain. Her memoir Risotto with Nettles tells an honest recollection of a life lived through food, a combination of the bohemian and the refined. She is modest, reflective and as she tells her story––of growing up in Italy, life under Mussolini, imprisonment for anti-fascism, and her career and marriage in Britain––she does it with such personality and sincerity that you feel you are treading the path with her. The great shame is that many of her books are now out of print, though Amaretto, Apple Cake and Artichokes––a recent collection of some of her recipes––is still available. Del Conte’s writing is informative, educative and places food firmly in its context, both historical and social, as well as creatively. Just as Italians learn their craft in the kitchen of mothers and grandmothers, she passes on her knowledge to us. Hers are not just recipes: they are almost encyclopaedic, personally-delivered history lessons given in the kitchen of a chic and knowledgeable Italian.

One of Del Conte’s most loyal disciples is Nigella Lawson, whose books have brought me endless gratification. She knows how to cook and she really knows how to write (and so she should, with a degree from Oxford and a job as deputy literary editor of The Sunday Times age 26). Her recipes contain more than just directions, they are embellished with descriptions which make it feel as though she is looking over your shoulder and guiding you as you cook.

Like Del Conte, each of Lawson’s recipes is preceded by an explanatory note; an anecdote, a story of how the recipe came to be, a little advice or a pithy observation. To look through her books is to take a journey into her mind. Her knowledge and appreciation of food is abundantly clear in her descriptions; she makes use of adjectives like no other and her unique way with words never fails to raise a smile. Nowhere else would you find the words schmaltzy and sprauncy, recipe titles like Chocohotopots and Blakean Fish Pie, or the caution to wear rubber gloves to deal with beetroot “unless you want a touch of the Lady Macbeths.” As I read, I can taste and feel, “the glottally thickening wodge” of chocolate ginger cake, sticky and warm in my throat, and that is her art.

Lawson guides her readers on a journey: through food history, through her past, and through the pleasures of cooking. Hers are books in which I can bury my nose for hours; they are pieces of literature in their own right. She is sensual. She has a true understanding of the way food feels: in our hands and in our mouths; physically, emotionally and spiritually. She also reminds us that cooking should be fun, giving us pleasure to make and in turn to those we feed.

Also from the school of the well-read comes Tamasin Day-Lewis, daughter of the poet Cecil Day-Lewis and sister of actor Daniel, who read English at Cambridge and whose literary intellect shines through in her writing. I cannot help but laugh at her observation of the “toenaily bits” found in stewed apples that haven’t been properly cored and, when I read the following I am transported to another land (via the bakewell tart): “the tart tin returned picked clean as a skull. The cream came out of the silver jug in clots you couldn’t control and began to turn to butter on the slice. The jam oozed and wept.”

Nigel Slater, too, has built his name on the foundations of fluent and easy writing. His style is stripped-back, he writes as he would speak and more to the point, he writes how he feels. The Kitchen Diaries read like a stream of kitchen consciousness; he explains that, “More than a diary, this is a collection of small kitchen celebrations, be it a casual, beer-fueled supper of warm flatbreads with pieces of lamb scattered with toasted pine kernels and bloodred pomegranate seeds or a quiet moment contemplating a bowl of soup and a loaf of bread…What intrigues me about making something to eat is the intimate details, the small, human moments, that make cooking interesting.” The recipes provide the springboard for his imagination, emotions and sensations, taking us with him as he cooks, eats, writes and feels.

We journey, too, with Yotam Ottolenghi, whose food transports us around North Africa and the Middle East, but whose words are equally moving. He muses, “I love the little see-through plastic boxes in which saffron is often sold: they look like miniature treasure chests, encouraging you to treat the golden, jewel-coloured threads within with the reverence they so richly deserve.”

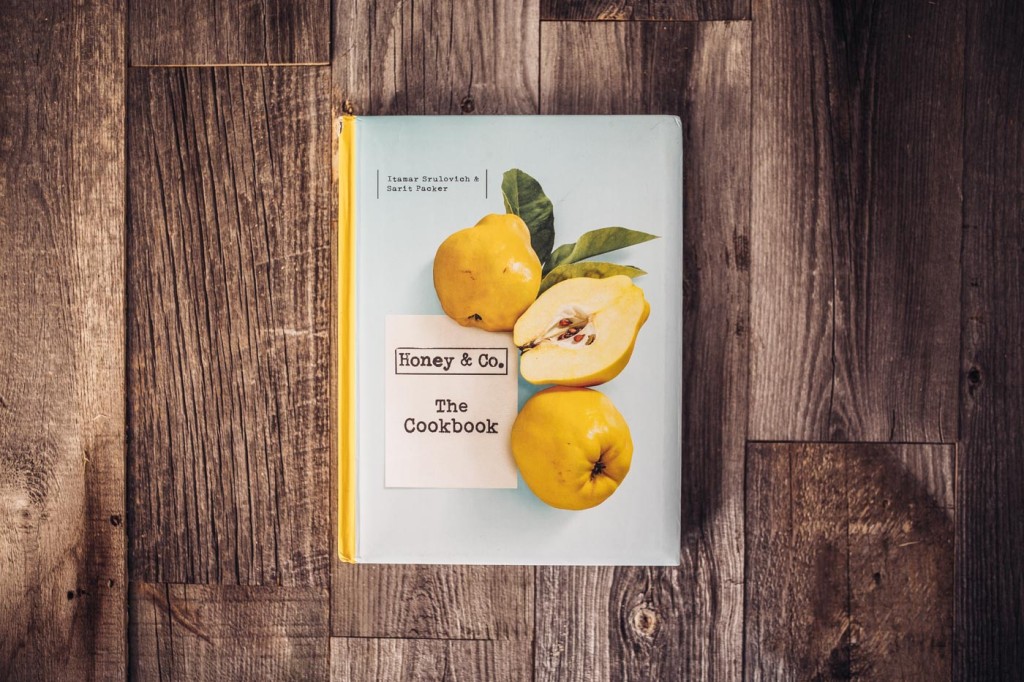

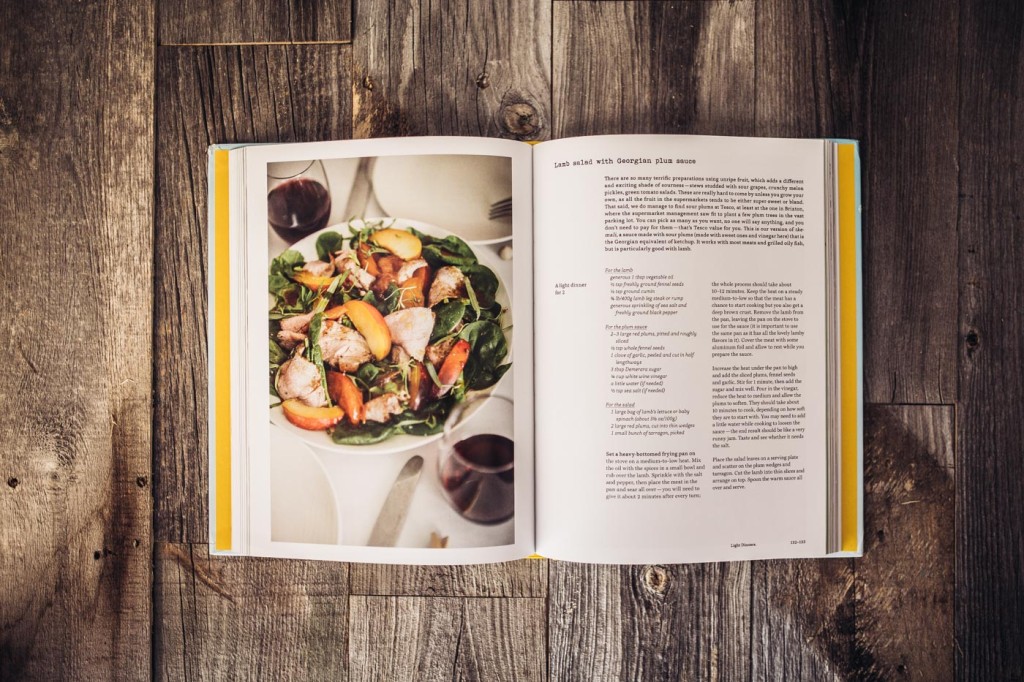

And give me any day the sweet, humble writing of Honey & Co’s Sarit Packer and Itamar Srulovich, whose books are full of little tales, but are nowhere more captivating than when they speak of their love for one another and for food. Through their books is the golden thread of a conversation between the two of them, like lovers catching one another’s glances across the kitchen:

“This cake, like many other things in this book, is tailored to my husband’s taste…Working and living together, there are plenty of things we don’t agree on…however, this dessert is a good place for us to put our differences aside…Itamar says this cheesecake is too sweet for him, but I notice that he always finishes his portion.”

Their books tell light-hearted, modest stories, mostly about the people they have met along the way and who have made their little restaurant into the well-known and loved haven that it is.

I could go on about the joy these cookery writers (and many more) bring me, just as I can endlessly read their books. I love nothing better on a Sunday morning than to get back into bed, steaming mug of tea beside me, and to read and re-read my recipe books.

A rare commodity is the truly great food writer, who expresses and articulates what most of us couldn’t even begin to. This is writing that stops you in your tracks, fires up your imagination and hauls you by the senses into another world. Some days, I don’t even get around to making anything. You can have your detailed instructions, TV shows and stunning photographs; I’ll take the writing every time, because nothing gets deeper into the soul or into the head, heart and mouth of this cook than a masterful way with words.

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.