The Booze That Built America

During Prohibition in major cities across the United States, crime bosses set the stage for future generations of organized crime, often at a brutal, bloody expense.

Were they bad men or did they just do bad things?

When we take a second to go beyond the cartoon-like archetype of a 1920s gangster, that slick-suited wise guy finishing off an enemy with the same moral regard he’d maybe finish off a steak, we might see something different. Something that has us question—those of us living in a progressive, post-Prohibition twenty-first century—if could we really say for certain we’d know which side of the law we’d be on.

If the tables were turned and we found ourselves at the cusp of a dry decade, newly immigrated to a country, would we shy away from an opportunity that granted a sense of community, respect and wealth beyond anything our poverty-stricken ancestors might have imagined?

For many of Prohibition’s most notorious figures, that’s exactly the question they found themselves facing.

To be clear, the men who profited most handsomely from Prohibition were not heroes. But they are a fascinating study in the viral effect of capitalism—what happens when a thirsty public is willing to look the other way, and the sinewy crime web such hedonism creates.

Pick any one of America’s most influential cities and, no doubt, you’ll find a fingerprint of Prohibition hidden somewhere along its streets. Understanding what drove these underbelly factions to begin, thrive and eventually crumble can be the subject of a lifetime of study, but even an overview of some of the largest smuggling outfits gives us a glimpse of humanity’s reaction to such unusual circumstances.

THE CHICAGO OUTFIT

The Windy City of the 1920s is synonymous with one man: Alphonse “Al” Capone. Arguably the most famous mobster in the American memory, Capone surprisingly was not the founder of Chicago’s underworld, but a later player who stepped in to reign.

Founding credits more duly go to Giacomo “Big Jim” Colosimo, who at the turn of century had gradually built up power in Chicago through his network of brothels and a pre-mafia extortion calling card known as the “Black Hand.” Predominantly utilized by Sicilian and Italian immigrants, “Black Handers” would send letters to local merchants stamped with a black hand or dagger and demand money under threat of vandalism, pain, or even death if refused. Eventually, the Black Hand came for Colosimo himself, at which point he reached out to his nephew, New York-based Giovanni “Johnny” Torrio, for help.

When the National Prohibition Act passed in 1919, Colosimo wanted no part of the illegal liquor trade, something Torrio was convinced could bring in easy cash. So Colosimo was shot and killed in May of 1921—something most sources claim Torrio was behind. With Big Jim out of the way, Torrio was free to capitalize on the increasing demand for booze. Along with Capone, who later joined from New York, he established the Chicago Crime Syndicate, a lucrative grid of speakeasies and bootleggers on Chicago’s South Side.

It wasn’t long before Chicago’s north—and largely Irish—side felt the competition. Although Torrio had tried to keep peace between various ethnic neighborhoods and gangs therein, the potential profits from Prohibition alcohol were so high that turf wars proved inevitable. Dion (Dean) O’Banion, leader of Chicago’s North Side Gang, had previously struck a deal for a share of Torrio’s profits, but that soon wasn’t enough. As Torrio’s men encroached upon O’Banion’s territory, O’Banion retaliated by arranging for Torrio to walk into a brewery raid led by police, swindling him out of half a million dollars just prior to doing so.

As a result of O’Banion’s double-cross, the Torrio-Capone outfit had him killed. He was shot at his flower shop and although neither Torrio nor Capone were ever charged with his murder, O’Banion associates Hymie Weiss and George “Bugs” Moran wouldn’t forget it. The ensuing Chicago Beer Wars were a direct result of this north against south crusade, during which an attempt on Torrio’s life prompted him to leave Chicago and return to New York. Capone was left in charge.

The transfer of Torrio’s power and profits to Capone was a shakeup within Chicago’s underworld hierarchy, one that routinely ended in street corner shootouts and bloodshed in diners and alleyways. By the end of 1926, over seventy mobsters had been shot, bludgeoned, or stabbed to death; over fifty more would be killed by the end of 1927.

At the same time, Capone was increasingly in the spotlight; a lover of public attention, he regularly called press conferences, gave money to reporters, and referred to himself as a “public benefactor” who simply gave the people what they wanted, i.e. alcohol. Although no witness against Capone could ever be brought to court—a result of the “Chicago Amnesia” effect with which his enforcers were credited—his consolidation of power was evident. His enemies dwindled and political alliances went up.

After a truce was called on the Beer Wars (at Capone’s request), his popularity surged further. It would take new tax laws and a Great Depression to finally bring him down. He died in Miami in 1947 due to complications from chronic syphilis.

THE NEW YORK OUTFIT

“A real G-D crazy place” is what Charles “Lucky” Luciano is once quoted as having said about Chicago. And yet, his New York was far from a sane haven.

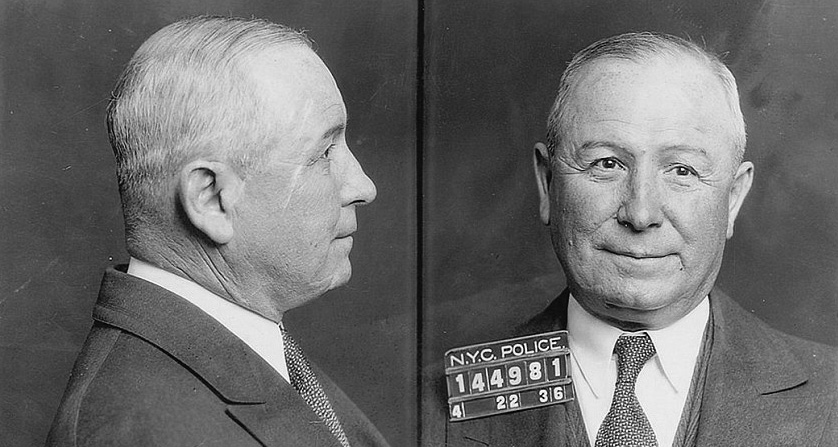

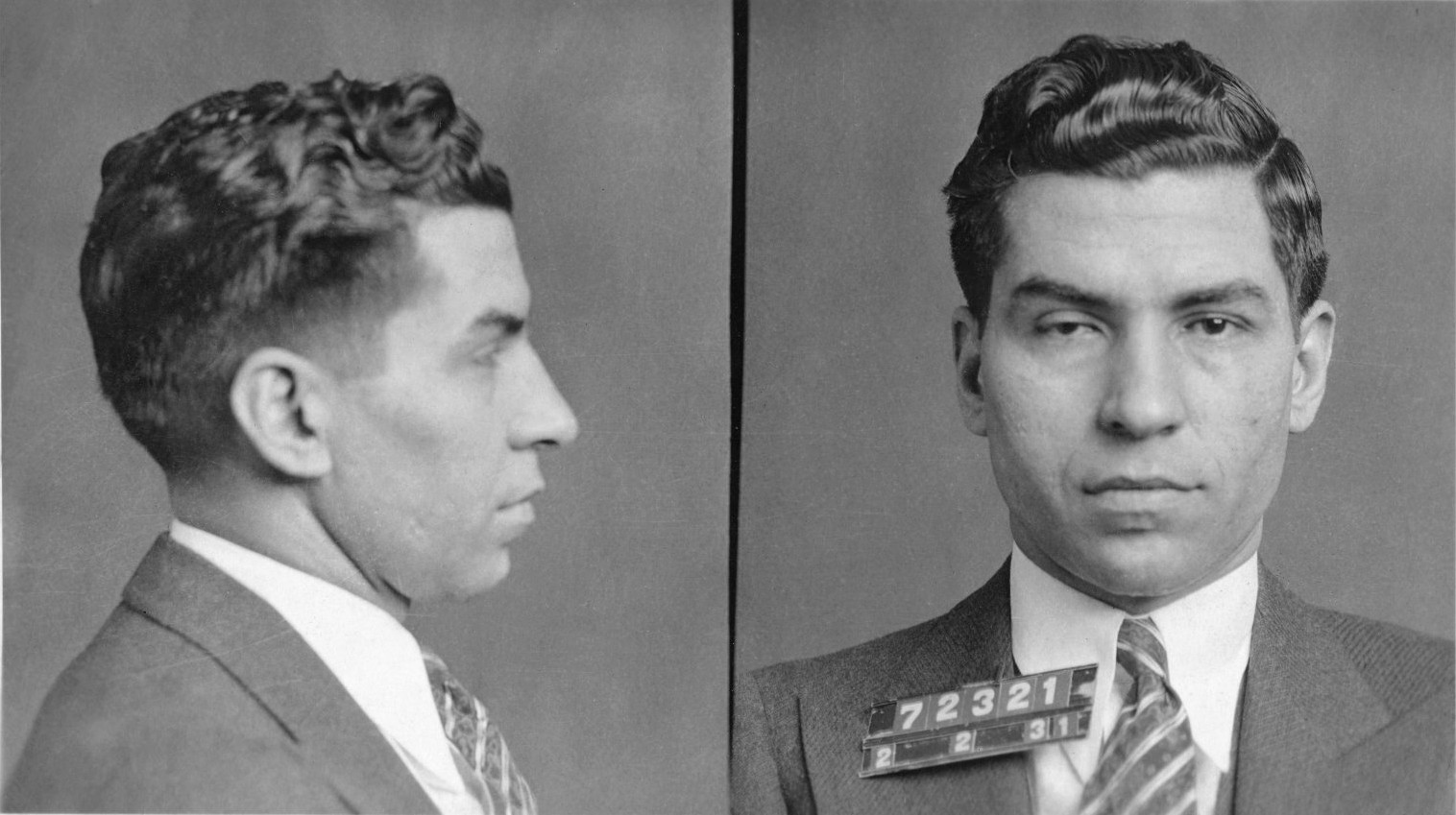

Sicilian-born under the name Salvatore Lucania, Luciano gained notoriety during Prohibition when Manhattan’s Lower East Side, a prime location for receiving liquor floating in from Rum Row, was predominantly controlled by Sicilian and Italian gangs. Having a monopoly on the illegal liquor market meant that among these gangs were continual power grabs and shifting alliances throughout the decade, but eventually Giuseppe “Joe the Boss” Masseria rose to the top.

Luciano later became Masseria’s second-in-command, but not before first mingling with notable Jewish forces including Arnold Rothstein, Meyer Lansky, and Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel—something uncommon for Sicilians to do at the time. All were involved in the bootleg trade with other unsavory spheres mixed in, and all were colleagues in the process. Luciano, though, always had a way of coming out on top.

Luciano’s ability to organize and still remain faithfully uncommitted to any one head except his own could be how he eventually overthrew both Masseria and a later Sicilian boss, Salvatore Maranzano, to become the true capo di tutti capi—boss of the bosses—by the start of the 1930s. As Prohibition ended, it had also spring-loaded Luciano’s influence so he had enough power to create the Commission, a forerunner of the American mafia today, delegating authority to New York’s Five Families and mafia operations throughout the country.

Despite evading capture for alcohol smuggling, bootlegging and murder during Prohibition, Luciano was eventually convicted of forced prostitution in 1936 after Eunice Hunton Carter, New York’s first black female district attorney, suspected a link between prostitution and the underworld. Sentenced to thirty years in prison, Luciano was later released and deported to Italy where he died of a heart attack in 1962.

THE ATLANTIC CITY CONNECTION

Much to the chagrin of its upstanding citizens, Atlantic City in the 1920s earned a reputation for organized crime that was just as prominent—if not more so—than its family-friendly boardwalk.

Enoch “Nucky” Johnson, for one, might take credit for that fame. As city treasurer, Johnson was keenly aware of what made the city money—and it wasn’t soda pop or saltwater taffy. A landing spot for smuggled booze, Atlantic City quickly became a go-to for gangsters, bootleggers and vice-seekers. During Prohibition, Johnson’s paid-for protection enabled speakeasies, brothels and gambling halls to flourish, so much so that the city was the natural choice to host the Atlantic City Conference—more commonly referred to as the “Mobster Convention”—by 1929.

Although details on the convention vary, it’s believed to have been a meeting between influential Prohibition figureheads Capone, Luciano, Lansky and Torrio, among others, to decide how to best handle rising supplier costs from liquor manufacturers abroad. Others sources claim it was an opportunity to discuss how to diversify revenue due to the increasing likelihood that Prohibition would be repealed. Still others argue the convention was actually an intervention to deal with Capone’s rising visibility and violent instability. Regardless of the summit’s specifics, Atlantic City was a gangster magnet. It was a strategic portal for both Chicago and New York, as well as a helpful lifeline to further smuggling in Florida, Cuba, and the Caribbean.

——

Like most things after October 1929, the Great Depression put a heavy break on the reverie of the Roaring Twenties. After Prohibition was repealed and the nation declined into unemployment, homelessness and hunger, there was little tolerance for the fur-wearing, bulletproof-vehicle-driving capos that had secretly come to dominate the economy. New federal initiatives were ushered in to eradicate corruption—and one could say the persistence of organized crime today is the extent to which they were successful.

Prohibition Examined is an ongoing editorial series exploring the origin and history of one of America’s most infamous eras. Read Chapter I and Chapter II.

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.