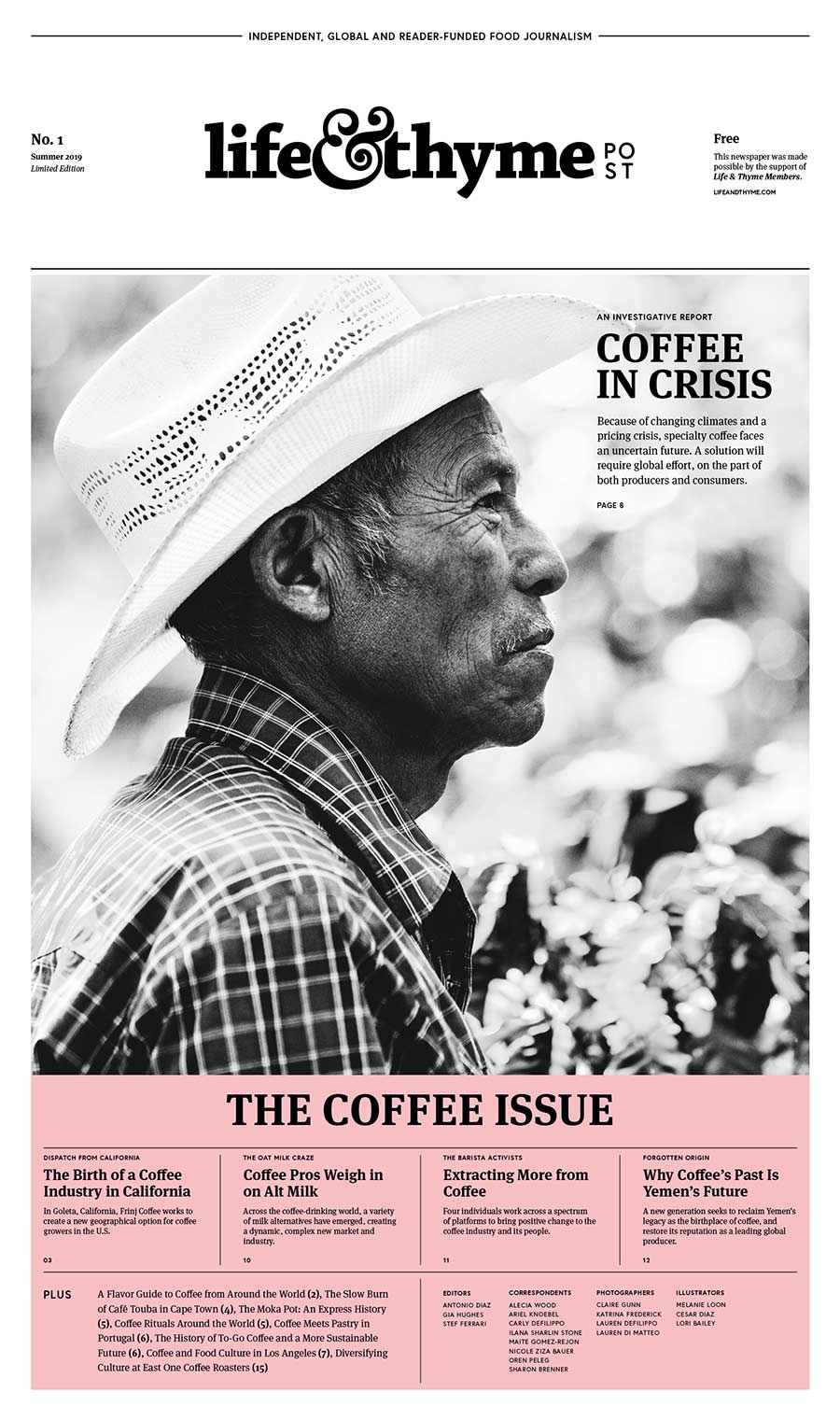

This story can also be found in our inaugural issue of Life & Thyme Post, our limited edition printed newspaper for Life & Thyme members.

Countless cups of coffee are enjoyed all over the world each day. Said to have originated in Ethiopia, trade and migration spread coffee from Africa to Europe, Asia and beyond, with unique regional traditions developing around the sourcing, preparation and enjoyment of this global beverage. It could be a lengthy, slow interlude, like the hours-long coffee ceremonies of Ethiopia that transform green beans into brewed cup via clay pot, or Italy’s ultra-speedy affair, churning out umpteen little espressi at the bar for hasty patrons throughout the day. From coffee industry professionals to local chefs, we spoke with experts to understand how coffee is brewed and served the world over—and why a seemingly simple cup of joe remains such an important ritual, often signalling a moment for connection and pleasure, no matter the time and place.

Sweden

“It’s not a cup of coffee consumed sitting in front of your computer; it’s a small, slow moment,” says Anna Brones, author of Fika: The Art of the Swedish Coffee Break. “Fika can be used as both a noun and a verb. So you can fika, and you can also have a fika. In general, it’s a break from the routine.” You might fika with colleagues, friends or just yourself; you could also enjoy something sweet like a kanelbulle or a kardemummabulle—Sweden’s signature cinnamon or cardamom buns. Traditionally, filter coffee (bryggkaffe) is taken, with cafés offering a refill called a påtår, or “second cup.”

Brones’ favorite element of the Swedish culture of fika is the fact that it brings people together over conversation. “You don’t grab a coffee to go and drink it while driving in your car. You take a break, sit down, and enjoy the moment and the person you’re with. We could all benefit from more regular, small doses of slowness like this in our everyday lives.”

Italy

Coffee punctuates the rhythms of each day in Italy, typically kicking off with a morning brew made at home in the nation’s ubiquitous moka pot, followed by an espresso or three at a café (called a bar in Italian. Caffè means “coffee,” and is the word used to order an espresso) as the hours roll on. “When we meet a friend or go to a neighbor’s house, we always ask, ‘Do you want a coffee?’ Coffee is an excuse to talk, to have a connection with people. It’s very important for Italians,” says Francesco Sanapo, owner of Ditta Artigianale in Florence. While Italy is still quite new to the third wave philosophy, Sanapo’s stylish café is arguably the most important leader in that field there.

Compared to Italy’s bar experience, the mokas that appear in every Italian kitchen are a somewhat slow affair; fill the base with water, put the filter basket on top and place coffee grounds inside, screw the top on and place the moka over direct heat, then wait for the syrupy coffee to fill the top of the brewer. “Do you know the etymology of the word espresso? It means ‘fast.’ We never sit down; the espresso is drunk always at the counter,” says Sanapo of the coffee enjoyed outside the home, adding the traditional Italian blend of arabica and robusta beans makes for an intense, bitter brew. “Coffee for Italians is the most important beverage in our lives. After water, for sure it’s coffee.”

Turkey

The cezve, a small brass or copper pot with a long handle, is definitive of Turkish coffee, which centers on a brewing process where very finely ground coffee is heated with water in the vessel over an open flame. It’s then served unfiltered, often with sweets alongside, with the delicate grounds settling at the base of the cup. “Turkish coffee culture began when the Ottomans first brought coffee and this brewing method back with them from Yemen,” says owner of New Orleans-based Specialty Turkish Coffee, Turgay Yildizli. “It became popularized in the sixteenth century with the opening of the first coffee houses.”

“In Turkey, hospitality is extremely important and coffee became an indispensable part of that,” Yildizli continues. “It became so popular that brown became known as kahverengi, or ‘coffee color.’” The former World Cezve/Ibrik Champion, Yildizli says the word ibrik is often used interchangeably with cezve, and is an Ottoman Turkish word originating from the Farsi word for pouring water.

“Over time and through the expansion of the Ottoman Empire, this brewing method spread over a large region encompassing the Middle East, Turkey, Greece, the Balkans, Russia, and northern Africa,” Yildizli says. “In each region, the method became entwined with the culture and changed to reflect the culture it is a part of. [It can be] different from region to region, city to city, and even family to family.”

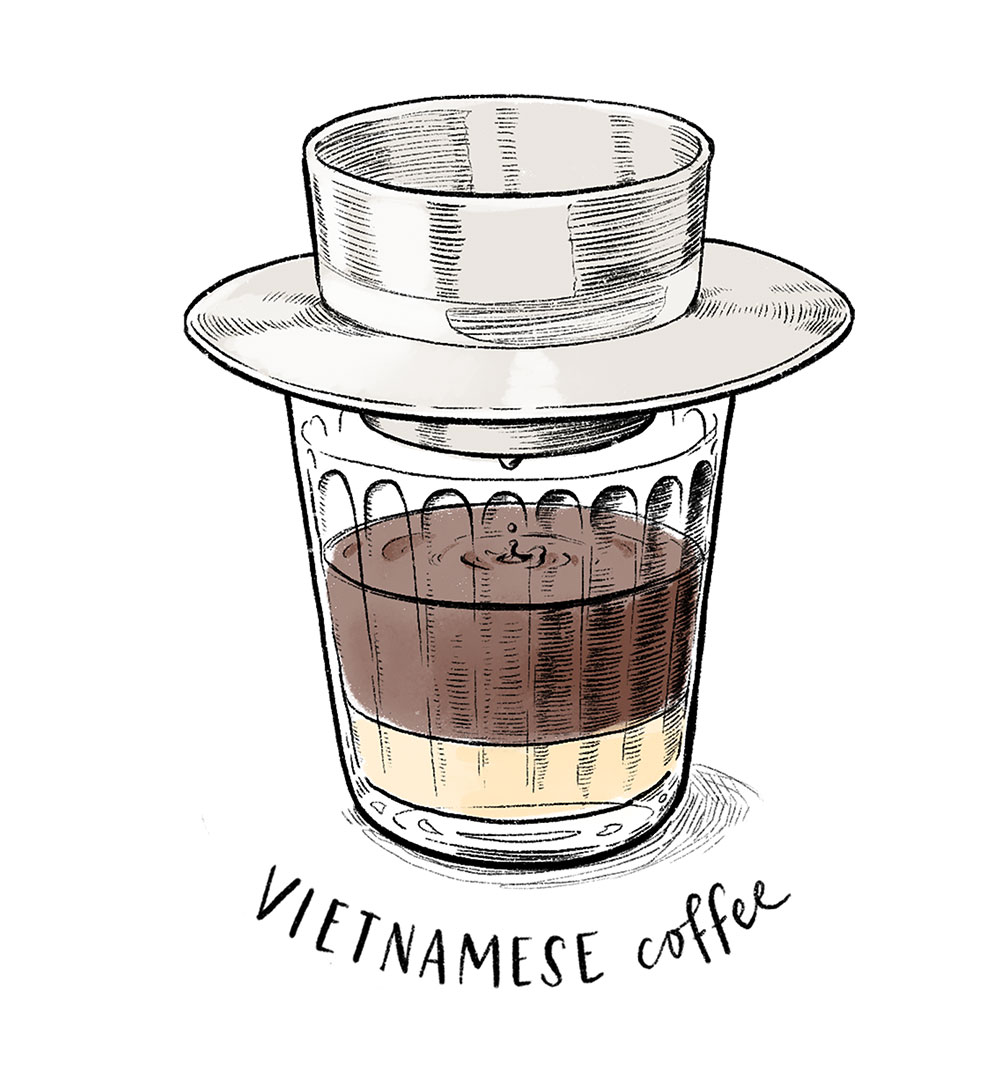

Vietnam

“In Vietnam, people drink coffee all day, many times a day,” says Sahra Nguyen, a first generation Vietnamese-American and founder of Nguyen Coffee Supply—a Brooklyn-based importer and roaster that works with green Vietnamese beans. “It’s how people socialize, how people spend time together. It’s an extension of their homes.” Traditionally, Vietnamese coffee is brewed using a phin, a tin, aluminum or stainless steel filter that’s placed over the top of a glass and filled with coffee. “I’d describe it as the intersection of the gravity method and immersion, because you’re getting an immersion with the grind similar to a French press; and you also pour the hot water into the phin, but it’s not as quick as a pour-over. For many decades, Vietnam had no electricity, so I think it’s very reflective of the country and the culture.” The brew is espresso-like—thick and concentrated—with a strong, robust flavor and nutty, chocolatey notes thanks to the typical use of robusta beans. Nguyen points out that robusta beans have sixty percent less sugar and sixty percent less fat than arabica beans as well as almost twice the caffeine content. She also shares that there are three commonly served coffee styles: cà phê đen (black coffee), cà phê sữa (coffee with condensed milk), and cà phê sữa dá (iced coffee with condensed milk). “Having a glass of cà phê sữa on the sidewalk or in a café with open windows is an integral part of my experience in Vietnam,” says Nguyen. “I couldn’t go a day without at least one cup of it.”

Malaysia

In Malaysia, kopitiam translates to “coffee shop.” These all-day haunts serve breakfast (like kaya butter toast, slathered with coconut-pandan jam), lunch and dinner, plus a selection of coffee styles based on black kopi beans, which are roasted over charcoal with sugar and butter or margarine. “It isn’t a surprise to see babies all the way through great grandparents going to the same kopitiam on the daily,” says Moonlynn Tsai, co-owner and operator of Kopitiam in New York City’s Lower East Side. “Throughout Malaysia and Southeast Asia, most families have their own preferred kopitiam that serves as a casual gathering place. It’s similar to the Cheers bar where everybody knows your name.”

Bringing Malaysian coffee culture to Manhattan, Kopitiam prepares kopi-o (black coffee) by placing the coffee in a sock-like fabric filter that sits atop a metal pitcher, which is then covered with boiling water and left to steep, similar to a pour-over. There’s also bek kopi, or white coffee. “It’s a greener kopi bean pulverized down into an almost powdered form with sugar and evaporated milk added to it. We then pull the coffee, which results in what I like to call a ‘Malaysian latte,’” explains Tsai, noting the drink has a nutty character and creamy taste with a third of the caffeine of other kopi-o based drinks. One of Tsai’s favorites is kopi tarik, which is kopi-o mixed with condensed and evaporated milk. “It pairs so well with the strong and spicy flavors of Malaysian cuisine.”

Mexico

“My parents always have people over; and no matter what time of day it is, they always offer a little bit of coffee, and it has to be café de olla. It’s very traditional Mexican.” Born and raised in Oaxaca in Mexico, Bricia Lopez co-owns Guelaguetza in Los Angeles, where the family-run restaurant serves café de olla according to tradition, brewing the coffee along with cinnamon and brown sugar in a clay pot (olla is the word for an earthen cooking pot). “When you’re Mexican and you go to a Mexican restaurant, and people offer you coffee, you always ask, ‘Oh, but you have café de olla?’ which typically means a sweetened, cinnamony coffee.”

Typically, the heady black coffee is brewed with grated piloncillo—a compressed, raw cane sugar that’s formed into little cones—along with the spice, which is then strained before serving. Lopez says it’s just as common at home as it is at taco stands. “It’s almost like water in a way. People always have café de olla,” she says. “In Mexico and Oaxaca, coffee is drunk in the morning and at night. Before you go to sleep, you drink coffee—which is a crazy thing!”

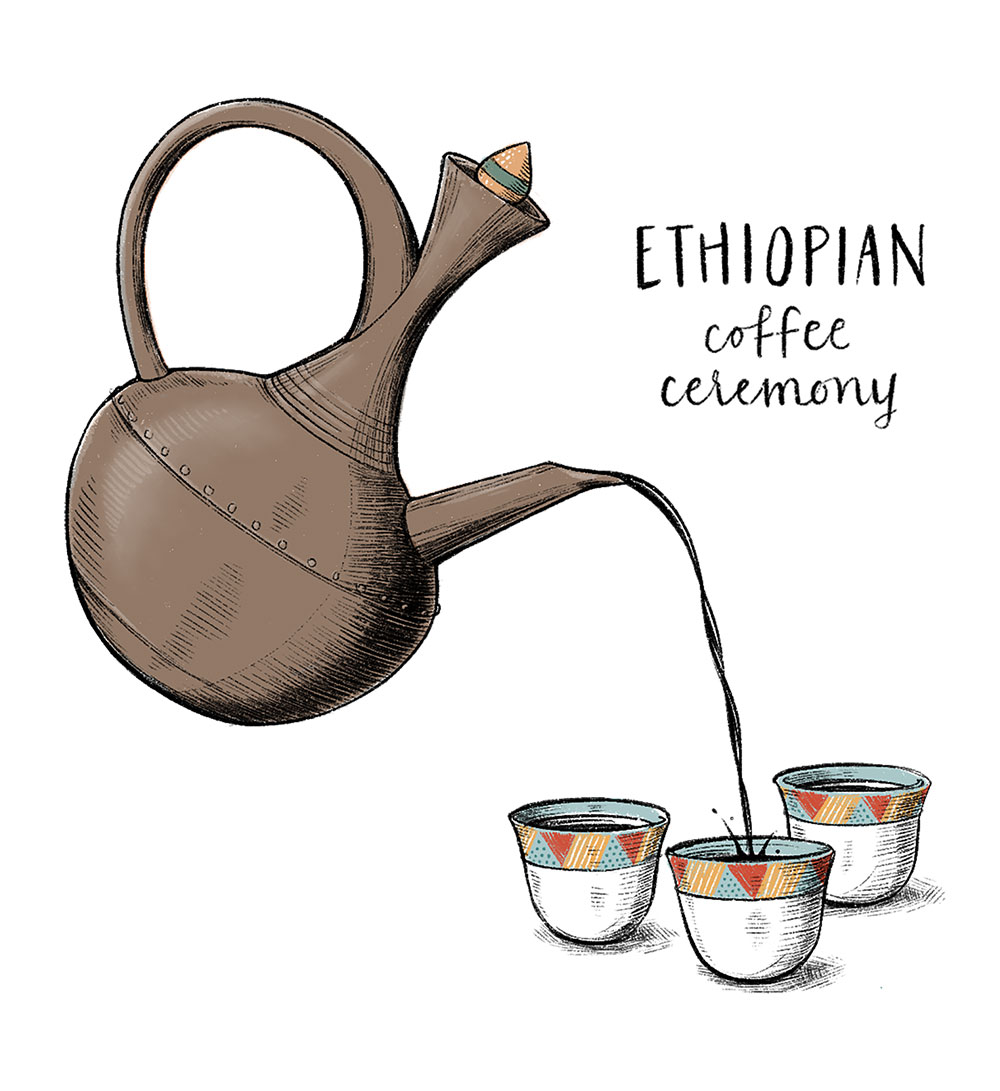

Ethiopia

“We’re one of the biggest coffee producers in the world, but one of the least exporting ones because we’re massively consuming it locally. We wouldn’t survive without coffee,” says Yohanis Gebreyesus, an Ethiopian chef based in Addis Ababa and author of the Ethiopia cookbook. Ethiopia is famous for its elaborate coffee ceremonies, where the beans are roasted, ground and brewed in front of guests using a clay pot called a jebena.

“There are three levels of coffee. The first cup is called abol; it’s the most condensed and the strongest coffee,” explains Gebreyesus. The same grounds are then brewed again with fresh water to make the second round of coffee, tona, and again to make the final round, baraka. Roasted barley and popcorn are often served alongside, and guests can flavor their coffee with sugar, salt, spiced clarified butter—scented with the likes of cardamom and fenugreek—or the fresh herb rue. “When we say buna tetu, it means, ‘Come drink coffee with me.’ It’s become so common that we use that name for all the coffee shops. On a daily basis, there are thousands of these small houses, buna tetu, where coffee from the coffee ceremony is available throughout the day,” says Gebreyesus.

He assures the use of the jebena makes all the difference. “It tastes so much better that I’m unable to drink coffee from a machine. It’s a very round taste—quite bold, a bit sweet, very creamy and nutty. In Ethiopia, every Ethiopian will ask, ‘Is it jebena coffee or machine?’ then make their choice.”

Brazil

Having grown up on a coffee farm in Brazil, Washington Vieira now works directly with Brazilian coffee producers via his U.K.-based import and roasting operation, Santu Coffee. Brazil is the world’s largest producer of coffee, and Vieira says that while the specialty coffee scene is booming there, traditionally it’s an ultra-sweet, bitter filter coffee that’s found across the country. “Everywhere you go, there’s free coffee. If you go to the dentist, you have free coffee. If you go to a gas station to fill your tank, you have free coffee,” he explains.

Brewed with a diluted sugar syrup, the coffee there is a dark roast that’s very finely ground, making for a slow extraction and a full-bodied, bitter flavor. “Bakeries are a common gathering place in Brazil. There aren’t really cafés [there], so it’s the place you go to buy breakfast, bread or milk to take home, and at the same time you have the chance to have a little coffee at the counter, which is a cafezinho,” says Vieira of the small black coffee that’s typically served. “It changes a lot from Rio to São Paolo. In Rio cafezinho is usually black, and in São Paolo it’s served with very hot milk.”

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.