At the heart of Mayan culture is the belief that everything—people, animals, even objects—possesses a divine life force, or k’uh. Although the Mayans are one of the most widely studied cultures in Latin America, the truth is that most travelers pass through this region without ever grasping any divinity whatsoever.

I, myself, am guilty of such pursuits. You see, for most Americans and tourists, the final two decades of the 20th century aligned this region, and its experience with tourism, far differently from the vision of its ancestors.

With ample supply and demand, labor from this region fueled the resort machine for those seeking to dip their toes into the Caribbean, many for the first time into the world of international travel. Prior to the boom, novice travelers like the newly married or retired took such adventures on cruise lines, rarely departing the confines of the ports of call. But marketers and travel agents stole the zeal from the seas by honing in on the all-inclusive concept, built on rotgut well liquor, nachos and hamburguesas. The results were remarkable, exploding Cancun’s tourism beyond its white sandy beaches to the rest of Quintana Roo, eventually finding its way south to Tulum, thus permeating the historic land of the Mayans.

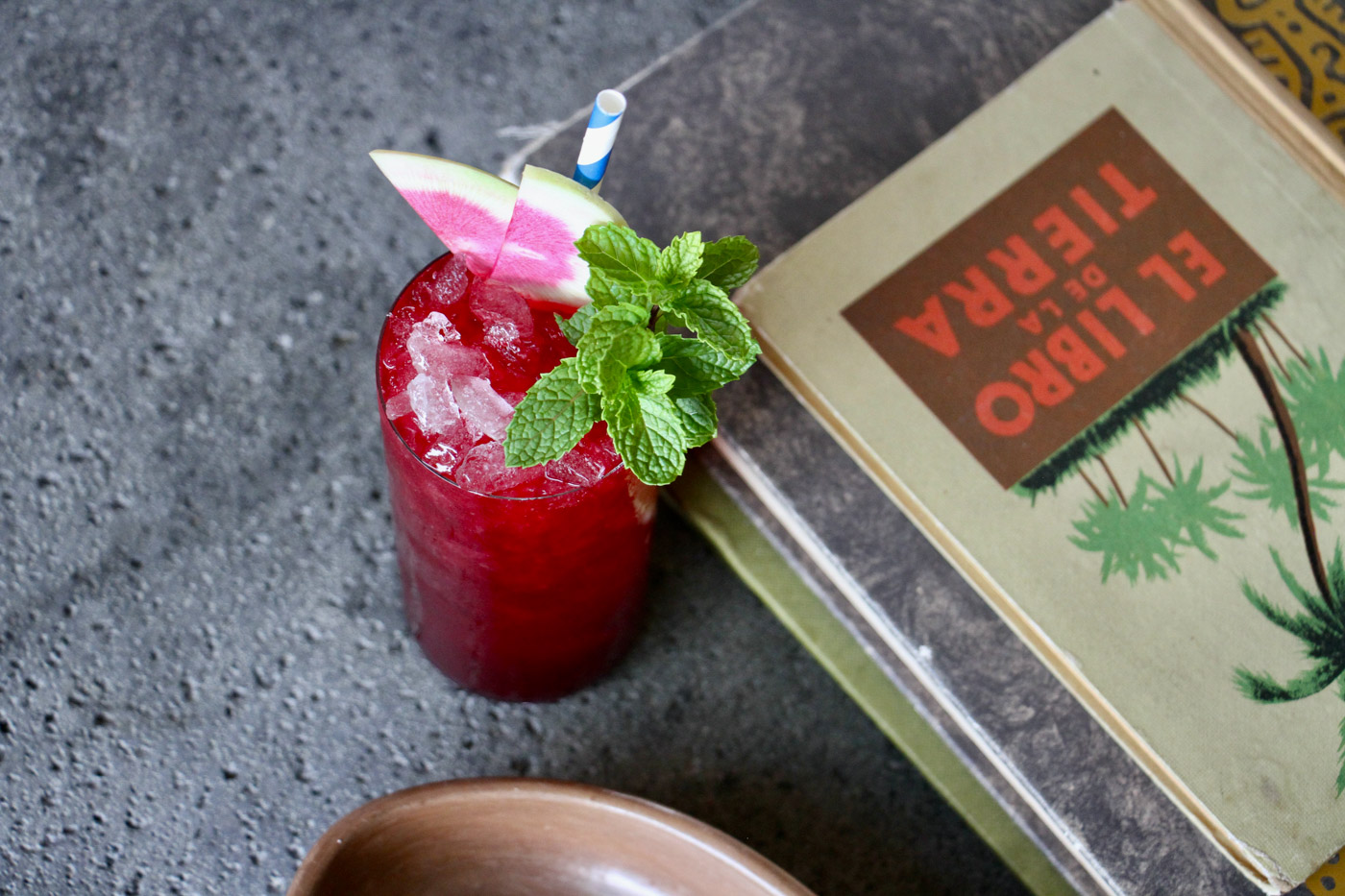

But for Chef Juan Pablo Loza, the Yucatán, as well as the rest of Mexico, remains misunderstood. The chef and I first connect over cocktails at his flagship bar, Zapote, named for the indigenous fruit-bearing evergreen trees that burgeon throughout the region. The concept itself uses all of the sapote tree as a resource—from the fruit for its cocktails, to its wood for the living room-like furniture, as well as its live-fire grills. Loza is no stranger to the cocktail scene, though he’s augmented his stance by partnering with Alberto González and José Luis León, the dynamic duo responsible for Mexico City’s Licorería Limantour, named one of the world’s 50 best bars for the past five consecutive years.

“We intentionally set out to venerate the ingredients of the Yucatán,” Loza tells me as I’m sipping on his manzano creation, a cocktail spiked with sotol, chiles, and the vibrant red-hued beetroot. But not all things go to plan. The Yucatán region is rich in nutrient soil, sunshine and water—producing its own vibrancy to native citrus, herbs and garnishes. Thus, the juices from the local beetroot varied boldly from its sister creation in Mexico City, causing the team to reformulate the drink, as well as the rest of the menu, accordingly based on the vibrant, local terroir.

It is said that if you have a cocktail, you feel like a new person. The problem is, this new man wants another cocktail. And before I even ask, Loza brings me something outside of the standard boundaries of tequila and mezcal. That’s where Roberto Brinkman comes in—his surname is of historic and proper Dutch nomenclature. Loza references this earlier, as much of the world only read the headlines regarding those fleeing the country. What we fail to realize is that Mexico has served as a refuge for immigrants throughout its history, especially during colonialism and following the exile of cultures throughout Europe, the Middle East and Africa.

Brinkman, who has built a career on promoting spirits, including mezcal, has brought his Katún brand of gin to Mayakoba from his home in Mérida. Like Loza, Brinkman is furthering the effort to raise awareness to the local ingredients of the Yucatán, as well as pay homage to his ancestors. The brand name, Katún, for example, refers to the 20-year cycle in the Mayan calendar, known for its predictive premonitions of periods such as fertility, famine or war. It’s a relevant double entendre for an outsider like me, as my intuition opens to the idea that this region is redefining itself as we speak, and perhaps more importantly, as I sip a spirit known less to this region, but authentically and entirely its own.

“I use over 20 elements for the maceration,” Brinkman shares as we stare at a table of local chiles, citrus, herbs and fruits. The combination of local citrus and chiles, specifically, is what makes Brinkman’s creation so unique and exhilarating—it’s the first and only gin from the Yucatán that’s perked and ready for a new kind of re-discovery from this historic region.

We put the Katún to good use with Loza back at the helm pouring his Mayayo creation, what he affectionately refers to as a Yucatán-style gimlet. Aside from the local, heady gin, the native sour orange serves both as a bitter balance not needing any bitters, as well as a garnish. “This fruit has the aroma of a tangerine, acidity of a lime, and the flavor of an orange,” Loza says as he deftly mixes the cocktail from shaker to shaker, using a stream-like pour from above his head to below his waist.

By this time, I’m getting hungry. Perusing the menu, one might sense Zapote’s gastronomy is more founded in Lebanese inspiration than any other influence. “Puebla is known for a heavy influence of Lebanese immigrants who brought tacos arabes, eventually becoming al pastor—but there’s a healthy influence of the Lebanese culture here in the Yucatán as well,” shares Loza. I’m nodding my head as Loza informs me more on my own Lebanese history than I personally know—enjoying the familiar and familial tastes as I manage and shake through his Shakshuka Yucatán, a tomato-habanero spiced stew, topped with a farm fresh egg, pepitas and goat cheese. His buttery and creamy guacahini is perhaps the best amalgamation of beloved guacamole and tahini—an unexpected gastronomic marriage.

I responsibly close my evening just before midnight, waking up to have an afternoon to explore a few of the other six concepts Loza has created in his role as Culinary Operations at Mayakoba. Unlike most other resorts in the area that feature the standard culinary concepts of Italian, French and other classic concepts, Loza has heartedly chosen to represent cuisines authentic or otherwise imported into the Yucatán. I opt to peruse the property on my chain-free rubber-soul bike until I arrive at El Pueblito to indulge in a cold Chela de Playa and tostada of local yellowfin tuna ceviche topped with crispy chicharrón. It’s a welcomed cerveza and dish that is purposeful in place and time. “In Mexico City, I look out my window and I see buildings,” says Loza. “But here, we wanted you to embrace the idea of hacienda, a place of private comfort and solitude.”

The next night, I’m invited to slowly savor Loza’s culinary excellence as he treats his guests to a tasting menu guided solely by ingredients from the Yucatán. The outdoor concept boasts family-style tables amidst an herb garden and a canopy of the honored La Ceiba tree for which it’s named.

“Tonight, we are serving you a fire-charred corn, puréed with coconut milk and accompanied by sustainable shrimp grilled over a live fire,” Loza explains. “There is life before this corn, and then there is life after.”

The corn is excellent. But the life after is the best premonition—perhaps it’s even the start of the next katún, promising the next 20 years will endow this region with the recognition it so earnestly deserves.

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.