It is late spring in a small field in the inland heart of the Yucatán Peninsula in southern Mexico. What grass is still in the ground is the color of late-season corn. If a part of it remains alive, it must be deep underground. For now, everything else is waiting to be called forward by the imminent arrival of seasonal rains.

It won’t be long now, and everyone and everything hopes that when the rain does finally come, it is not too violent an unleashing.

In the corner of the field, a man dressed in a huipil—a traditional loose white garment—tends to a fire on the edge of his milpa, a traditional Mayan smallholding. The fire is circled by large, irregular limestone rocks, chalky and harsh. As the man fusses over the fire, a score of people stand a few meters away, a murmur under the Ceiba tree—the only shade offered in this acre of ceremony.

At this time of year, shade is a benevolence.

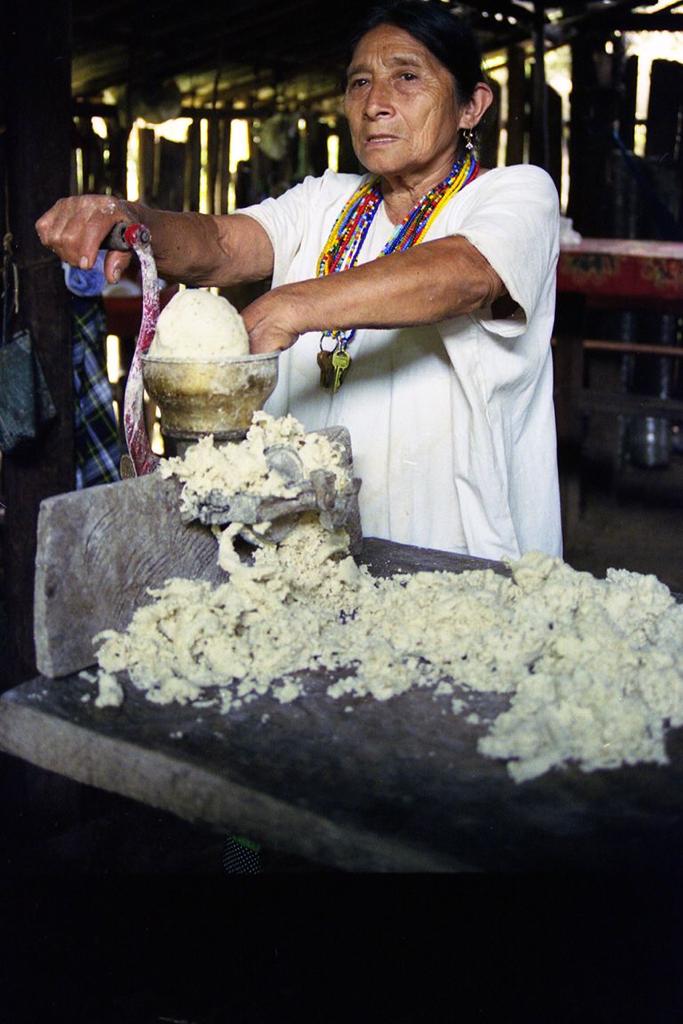

Of those present, a handful are engaged in the work of building the altar for offerings to Yum Chaak, the Mayan deity of rain. The rest busy themselves grinding roasted calabaza seeds for pepita molida—a mixture of ground roasted pumpkin seeds mixed with salt—a ubiquitous dish in Mexico’s deep south, the historic land of the Maya.

Around the fire, it is quiet. There is little to be heard save for the crack of burning branches and a single voice.

This is the voice of Ernesto Haw, the man in white, an elder in his community who has been participating in the ceremony of Cha’a’chaak his entire life.

The voice rises and starts to tell the story of the altar on which they will soon place their offerings. Later in the day, Haw will recount that this is now the sixth decade in which he has participated in this ceremony, calling Yum Chaak for the rains to come.

By the looks of things, the swallows who dive-bomb the path to the milpa this late afternoon agree that water is not far away.

More than anything, perhaps, Haw knows that beyond being a call for seasonal change, the story and the act they are involved in—and with it the ritual preparation and consumption of the tortillas, the pumpkin, the sweet potatoes—reminds those present of who they are. Whatever stresses and strains their days hold, however disparate the intricacies of their individual lives, this ceremony gives them time for respite. Through it, they are able to remember, and to recall that they are, simply put, Mayan. That they are joined together by who they are, their experiences and those of their ancestors before them.

The flowers nearby, the birds, the bees humming are present not simply as the adornment of nature this hot spring day, but as a context people understand just as if an uncle or grandparent were present.

Or, increasingly, absent.

To hear Haw intone, to experience his voice being carried on the lightly gusting wind, is to understand this act is one of survival—not simply of a human body given nourishment and sustenance, but of a people.

___

“In order to resist, we must remember who we are—and remembering is not a passive act. As Indigenous Mayans, the default process today is to cease to be, to die little by little. Only by choosing to be active, in our traditions, in our folklore, in our communities, can we continue to become who we are,” so says Pedro Uc Be, Mayan leader, poet and social and environmental activist at the forefront of the Múuch Xíinbal Indigenous collective.

Uc Be was born in the community of Buctzotz where he was raised working outdoors, tilling the cornfields and stewarding the land. His activism is steeped in the knowledge and emotional import of this upbringing; he has known from a young age how Indigenous communities plant and care for the food they produce, and that the truth of the human relationship with the land lies in the stories we tell of it.

“Our elders are ageing, inevitably, and they are struggling to complete the rites of the ceremonies,” Uc Be laments. “There’s also a lack of interest from the younger generations in the face of the lure of globalization, so knowledge is passing away without being shared. And when knowledge is not being lost, it is being co-opted and cheapened to peddle to tourists.”

Uc Be has dedicated his life to protecting the right to land and territory of the Mayan peoples, now particularly affected by megaprojects like the misnomered Mayan Train (Tren Maya), and multiple seemingly well-intentioned renewable energy ventures which exploit Indigenous land and people.

“We are losing our stories,” he says. “And with it, who we are.”

___

Food has always been central to resistance. It connects people to their culture and constructs identities based on histories of the land. It makes sense, therefore, that food production and preparation is intrinsic to the implications of power and politics. Often, however, the politics of consumption are rendered invisible by the necessity of food to our survival. Its mundanity—the everyday need for sustenance—allows it to slip into the foundations of systems of exclusion.

Indigenous, rural communities are uniquely situated with regards to the production of food; they are generally more in tune with the seasonal rhythms of planting and harvesting, and their land management practices are predicated around stewardship and sustainability. Globalized food production systems, by contrast, select plants for their ability to be produced en masse, creating a market in which traditional methods of planting and harvesting are forced to change in order to compete.

“Meanwhile, communities suffer from increasing iniquity and decreasing food sovereignty,” says Uc Be. “And this is to say nothing of the continued exploitation of land and people at the hands of large infrastructure projects like the so-called Tren Maya, and huge renewables projects which fail to understand the needs of the communities whose lands are being plundered.” The San José Tipceh ejido in the Yucatán Peninsula, for instance, which communally farms 1,468 hectares of public land, is currently fighting a photovoltaic park which will deforest 700 hectares of jungle in order to install 1,228,000 solar panels. The fight to protect Indigenous lands has been ongoing since 2016, although at present, the threat of biodiversity loss, crop damage, and loss of livelihood has failed to forestall the project.

Such unresponsiveness to the needs of the community of San José Tipceh does not bode well for the ongoing battle against the Tren Maya. The Tren Maya is the flagship infrastructural development project of the current Mexican administration, the López Obrador federal government in Mexico—a project that will drive a 932-mile-long line right through the heart of Mexico’s southern jungle. The second largest contiguous tropical forest in the Americas after the Amazon, this tropical forest is already contending with the side effects of logging companies, agriculture and species loss as a result of climate change.

The Tren Maya’s proposed route is due to run through 10 protected nature reserves, including the Calakmul Biosphere reserve. Here, 558 vertebrate species alone rely on protected wildlife corridors for the dispersal of their populations, and as a critical vanguard for their wellbeing. As such, thousands of species of plants, animals and insects—including jaguar, tapir, ocelot and the highly distinctive scarlet macaw—are at an increased risk of extinction, both as a result of the building of the Tren Maya and the ongoing detrimental effects of increased tourism in the area.

Local resistance organizations, alongside the Project on Organization, Development, Education and Research (PODER), have sharply criticized the endeavour, not least because of the biased presentation of information at community consultations, which took place before the completion of the environmental impact assessments. Only 1% of the national population took part in the initial referendums, which were used to demonstrate overwhelming support for the project. Later, when “public” consultations took place, they were closed forums involving only selected members of Mayan communities to participate, and they did not invite open dialogues where Indigenous people disagreed with the proposed plans. Moreover, consultations had little representation by women and the elderly—who are often at the forefront of experiences of displacement and destruction—and some resistance organizations critical of the project were denied access altogether.

“We are continually facing disinformation, bribery, coercion, blackmail, threats and violence—strategies we have seen acted out repeatedly for the last 500 years,” comments Uc Be. “The ideological apparatuses of the state have left communities here in a state of complete vulnerability. These projects erase our land and our way of being. They erase us.”

According to the Yucatán state government, another 24 wind and solar plants are slated for development in the coming years. Land claims for such projects are usually dubious, and because environmental impact reports are typically conducted after permits have been granted, as in the case of the solar park at San José Tipceh, the true extent of potential damage inflicted upon the land remains obfuscated until after land use has been approved, at which point it is too late to indemnify the loss.

This widespread pursuance of renewable energy projects is creating a seedbed of abuses which mimic the historic harms done by the fossil fuel sector. Dispossession, exclusion, half truths, unfair distribution of access to energy and resources—despite protection of the rights of Indigenous groups under ILO Convention 169 (also known as the Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, 1989, which gives Indigenous peoples the right to exercise control over their lands and ways of life), the renewable energy sector is ignoring social equity and human rights, and disregarding communities’ relationships with the land.

“Corporations regard the Mayan interior as a kind of terra nullius [land that is seen to be unoccupied or uninhabited, and therefore available for seizure] for infrastructural megaprojects,” says Jonathan Bonfiglio, Latin America Correspondent for talkRadio. “To them, the people and the culture that is thousands of years old are nothing more than a planning inconvenience. At worst, the traditional owners of the land are seen as uncivilized savages sitting on economically unproductive land—at best, planners in faraway capital cities think bulldozing them from their homes and their past is doing them a favor.”

___

Land losses suffered by Mayan communities over recent years, as well as those that continue to occur, make the ancient rituals more essential than ever. Given the context currently being lived, there is a more pressing need to cleanse the land and its spirit, and for a collective rerooting in cultural food practices.

One of these, the Jets’lu’um ceremony, undertakes exactly this—healing a land in crisis, asking that deities protect the animals and crops on which communities rely.

Jets’lu’um means to tie knots with the winds. It is a beautiful way of referring to the elaborate preparation and consumption of balché wine, crafted from the bark of the tree of the same name, and the honey of the endemic melipona bee. The wine is poured in the corners of a polygonal milpa, and a dough seasoned with pepita molida and wrapped in banana leaves is placed on an ofrenda as an offering to the deities.

The priest’s invocation of the spirits to protect the land indexes an intimate form of agricultural activity which is predicated on gratitude to and for the land. Whatever your beliefs on gods or spirits, this humbling of self in the face of much greater systems stands in stark contrast to the vast dystopian impositions of mass infrastructure planned and agreed on foreign lands.

___

As the Cha’a’chaak ceremony winds to a close, the breeze picks up and the air fills with the earthy, petrichor scent of coming rain. Haw stands and smiles. He is here; his community is with him. They have cooked together and they have shared food. And in doing so, they have renewed their memories and their sense of who they are as a people—the life of their community for another year.

Yum Chaak—they hope—has heard them.

Cultures the world over have long-established traditions, the overwhelming majority of which have their roots in food gathering, preparation and collective consumption. Far from solely being acts of history and memory, these traditions link communities to their land, their environment, their seasons, and to themselves.

Stories are what make us who we are. They remind us of our values when we face existential threat.

Mayans are full of stories. To urban ears, these recountings may seem opaque, lacking in the literal details and recognizable referents which characterize so much of modern discourse. Yet the stories heard where humans are fewer are not singular; they differ from the individuality of contemporary myth by being necessarily collective, infinite, and amount to a kind of protection in identification—a shield. Each story lost is another chink, an incremental weakening, in the armor—which, of course, is also the armor of environmental protection and custodianship.

Ritual, everyday acts of food culture, as well as more elaborate, symbolic seasonal gatherings are generally viewed as celebrations. But in reality, they are the continuing, active, necessary manifestation of the continued generation—survival—of a people.

___

As the sun begins its late-afternoon dip, Haw walks away from the field. He looks down at his bare feet as they touch the earth, and is grateful for the opportunity he has been given, to do all that he can do, and keep the voice of his father singing.

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.