Hospitality Is Resistance in Reem Assil’s Arabiyya

In Arabiyya: Recipes from the Life of an Arab in Diaspora, Reem Assil interweaves the politics of food with a celebration of the Arab table, and reflects on the work it takes to create a more equitable society.

It’s spring in Los Angeles as Reem Assil, the founder of Reem’s California, sits across from me on the patio of a bookstore in Echo Park. Around us, there’s a hum of chatter and the rhythmic flipping of pages as patrons slip between reading and conversation.

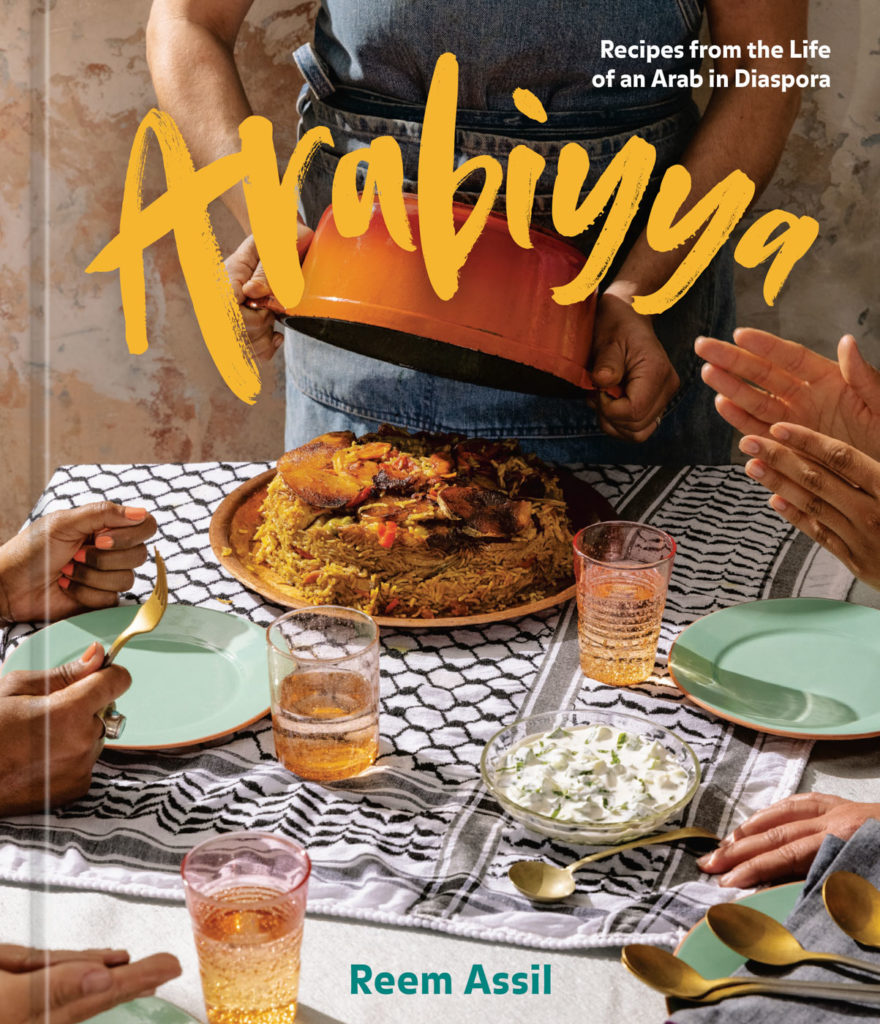

Assil tells me she’s wearing a shirt her son picked out for her between sips of green tea—a tonic for the wear and tear a book tour does to the vocal cords. She’s in town for a series of events around her first cookbook, Arabiyya: Recipes from the Life of an Arab in Diaspora. Ma’louba takes the starring role on the cover, being flipped out of a flame-colored Dutch oven as plates sit empty awaiting a scoop of the tower of rice and vegetables.

While Assil wanted to write a memoir, she was approached early on to write a cookbook. But it wasn’t until 2019 that a proposal was put together.

Arabiyya treads the territory between each, weaving personal accounts between recipes and framing history within the story of her own family. Assil writes with an immediacy, reminding us that the stories she tells are closer to our time than not, and with repercussions that have been codified into society.

In Arabiyya, Assil writes of her upbringing in Waltham, Massachusetts, and picnics with her grandmother in the San Gabriel Valley where they would escape the heat of the San Fernando Valley. She recounts the story of her grandmother’s expulsion from Palestine in 1948 during Nakba, and her mother fleeing Gaza in 1967 only to end up in Lebanon as it was on the precipice of civil war. She composes a love letter to her family, both blood and chosen, careful to not omit their flaws and contradictions, but instead celebrating their complexities as a testament to their humanity.

“We may never get to see our homelands,” Assil tells me as our conversation draws to a close. “But the concept of a free self-determined Arab people, that is a thing.”

I turn that term over in my head, examining the shape the word takes as she says it and the conviction that’s ingrained in its usage before asking Assil what it means to her.

“Self-determined is to have control over my own destiny, to live standing tall in my own dignity,” she says. “To feel connected, to love freely, and to be loved freely. And to feel whole, to live my best life, and not at the expense of anyone else.”

Read our conversation about Reem’s California, Arabiyya and more below:

—

In the title of your cookbook, Arabiyya: Recipes from the Life of an Arab in Diaspora, you use the term “in diaspora.” What does that mean for you to be living in diaspora?

We struggled with that subtitle because often, diaspora is associated with something sad and not to be celebrated. But for me, being in diaspora is like, I’m part of this larger global community of people who come from my lineage. There’s something beautiful about that—the idea that you can create community across borders, across oceans, and we are all connected through these cultural tenets, one of them being Arab hospitality. I wanted to take that and flip it on its head a little bit.

When did you start to approach doing a cookbook? What was that process like for you?

My career kind of catapulted faster than I anticipated. I had been working as a baker and in the industry in various realms with the idea that I wanted to start something. So I joined an incubator program called La Cocina in 2014, and it was there where I started to test my model with one farmers market where I was selling my flatbreads. Within a year and a half, it gained at least local attention in San Francisco.

Then we had our first brick and mortar in 2017. There weren’t a lot of people who were in the scene at that time, really leading with a clear, focused identity of Arab. But also with the social justice aspect of being an Oaklander who’s working in Black and brown communities—so there was something unique about my model.

We had been on Food & Wine’s top 10 restaurants, so some of the more mainstream food publications started picking us up. While that was amazing, it was a little overwhelming because by the end of 2019, I felt like my narrative was getting away from me a little bit.

It’s like I was being packaged as the meteoric rise of Reem Assil—even a brown girl can make it in the industry. I had seen behind the scenes actually how hard it was and how I was struggling. So throughout that time where people were like, “Write a cookbook. Write a cookbook,” I was like, “I’m just learning how to run a restaurant, let alone write a cookbook.” And I had a child somewhere in between there.

But that’s where the impetus came. When I was like, “I need my narrative back a little bit.”

Beyond your own story, in Arabiyya, you share stories of your family that are interwoven with the recipes. With the way we consume recipes now, the recipe itself is often so removed from its roots.

Exactly. And this was not easy. We went back and forth a lot, but I structured the cookbook around my somewhat nonlinear, but somewhat chronological narrative. If you think about it, it’s all the way up from my birth to when I started Reem’s. So I didn’t even get to cover the whole gamut. I stuffed it all into one epilogue, but really, what recipes I chose, and how I structured them, were driven by those five essays.

What was it like revisiting your family history to then turn it into a book?

It was very cathartic for me. There’s just so much I didn’t know about my family history or so much that I kind of knew, but didn’t understand the subtext of. My grandparents’ story, for instance—if you just look at that narrative and then you look at me, you’re like, “Oh my God, the two of them are so much more in me than I realized.” My grandfather (the entrepreneur) and my grandmother (the virtuous) take care of everybody and don’t take no shit.

But it also brought me closer to my parents; as an adolescent, I had a complicated relationship with them. To really see them as human with their own stories, I think it made them feel proud. And I think seeing that I’ve documented our family history in a book makes them feel really proud. It was a special and transformative process for me. And my relationship with my family is closer because of it.

Something I noticed in your book is that for each recipe, you have it in Arabic and in English. Do you think there’s power in the way you speak about things?

Absolutely. Just the fact that people associate hummus most with either Israeli food or Trader Joe’s, there’s a problem. I think there’s intentional and unintentional cutting food off from its lineage, and that’s a dangerous form of ethnic cleansing. For Palestinians, but also for Arabs in this country, it’s a form of oppression, right? To invisibilize us and to not give context. I tried to really bring that home.

I don’t necessarily think about ownership of food, but just origins of food, and the story they tell. And if we knew more about where our food came from and the lineage of that food, our consciousness might shift toward a more human-focused framework.

You can see that lineage in recipes like your rendition of al pastor, where you explore the Arabic roots of a dish that is often seen as Mexican cuisine.

Then when you dive deeper, you might ask: why did the Arabs flee to Mexico? What is their experience now? I’m fascinated by Arabs in diaspora, wherever they are. What was that interaction? The good, the bad and the ugly—all of it is important to know. I think food is more delicious when you know the framework of it. It’s just that much more spiritual.

It’s like when people say food is political. Inherently, it is. But it’s not enough to just stop at “food is political.”

Breaking bread does bring down some of the barriers, but it also leads to uncomfortable conversations. I think that with Arab hospitality, the thing I love about it is it does level the playing field of power. When Arabs are hospitable, they’re genuine. You invite anyone into your home, even your enemies. Even the people who are oppressing you—because your survival is contingent on that. There’s something really pure about that; it’s how we’ve survived generation upon generation. It’s just a virtue.

But beyond that, what is the obligation we have as the ones who come to the table with more power? How do we give that up? How do we sit and listen?

That’s so interesting—hospitality as resistance.

For us, resistance is just the fact that we exist. Existence is resistance, as we say. People use the term coexist. And I’m like, “Well, let us exist first. Then we could coexist.”

This goes beyond the question of Palestine. This goes to, what does it mean to be a restaurant in the middle of a Black and brown community? If you are coming to my restaurant, you are going to be forced to interact with the neighborhood my restaurant is in.

In this country, and especially in this industry, hospitality tends to be transactional and very sterile. In fact, when we were looking at subtitles for the book, we kept saying “hospitality.” And I was like, “That doesn’t sound right. Why am I so opposed to the word hospitality?”

In my restaurant, it’s really an ecosystem and an exchange. It’s an invitation. It’s not just, “I’m giving you this in exchange for this.” It’s like, “No, we’re in this together.” It’s not always about the customer.

The world of fine dining was, very much for me, like that. It’s not the way we do things in Arab culture. It’s very dynamic and usually people are bringing something. We’re here to invite the customer to be a part of this beautiful world we’re creating where anyone can come as they are.

At the end of the book you write about your experience at Dyafa, the San Francisco restaurant you opened in partnership with Daniel Patterson. You write about how you weren’t the chef people had in mind.

When I signed that partnership deal, I just had a baby. I literally opened a busy restaurant two weeks after I had my child. The repeating narrative was this put me on a pedestal as this super mom, but then held me up to the standards of this patriarchal chef and nothing in between. It was a really confusing place to be in. It was not in my nature to be a super mom or be a patriarchal chef. I was like a stranger in no man’s land because all I knew was how to cook my food and talk about my food.

I created this concept that attracted a lot of Arabs in diaspora, in particular. That was a really special thing about Dyafa. The people were coming, Arabs finally had this thing where the world could see their food as elevated, but it was not really much different than the food I was making at Reem’s. That was a real mindfuck, for the lack of a better word, like, “I’m supposed to be elevating this food.” And, “I only know how to cook what I could cook.”

I can do some fun, cute things, but I was getting molded into these Eurocentric methodologies. Then it gave me imposter syndrome about my credentials as a chef. People wanted to romanticize me, but I felt like I had become a token, a spokesperson.

What has the process been like in building a more sustainable workplace at Reem’s? Is that a collaborative process? Is there a struggle to build a workplace within a capitalist system?

It’s been a steep learning curve, to say the least, entering an industry that is so structurally set up against building social justice values. From the cost of food, to the cost of real estate in the Bay Area, if you’re going to be unwavering on the tenets of workers’ rights, then something else has to suffer for it.

For us, it is an opportunity to be creative in other facets of the business. I knew coming into this business I was going to be unwavering about worker wages and sustainability. The way I created my menu, what I chose to spend money on, even the ingredients—we had to be creative about that.

But there’s more to a good workplace than wages. Learning how to democratically run a business that is in a fast-paced environment where you have to constantly pivot and respond to trends because you need to keep your lights on—if you don’t get paid, you can’t pay your workers. It doesn’t leave much time to do that deeper transformative work. And I often joked in the beginning, saying, “I wish a union organizer would just come in and work with my employees to build their leadership, and then they can just tell me collectively what they want and my life would be so much easier.”

It’s so crazy. People are not used to the boss sitting side by side with their workers, asking them what they want. Inevitably, there’s a power dynamic there; I’ve had to grapple with that over the years. The best way, leading up until the pandemic, was to run my business as cooperatively as I could within whatever was feasible.

During those first two days of the shutdown, the onus was all on me, and my workers were demanding answers. And that was really, on the one hand, exciting. I was like, “They’re organizing in a way, even if it’s reactive.” But in the other way, I want them to feel empowered. How do they not feel empowered to help me think through this when I’ve been running the business? And I realize it takes a lot for people to internalize stepping in, that they are powerful and they have agency, regardless of whether you set up democratic structures.

That was something to grapple with for the last two-and-a-half years—I need to actually give up power in order for them to step into their power.

Before the pandemic, we set out a 10-year vision. We said by year 10—that was 2030—Reem’s would be worker-owned. We were going to build this asset, and then I was going to sell it back to the employees. And then I thought to myself, “Well, that sounds a little Columbus. Why should I build it and then give it? Let’s build it together.” Because I know in the tenets of organizing, when you fight for something, you have a stake in it.

Workers are not going to get involved unless there’s something at the end of the road for them. Ownership, to me, was the inevitable answer. They might not get a huge profit share right now, but the act of having a say in a business that inevitably impacts your life is really powerful. We set out to do that in the spring of the first year of the pandemic. We built an apprenticeship program called Sumud, which is the Arabic word for the Palestinian struggle.

We engaged in it for 15 months, myself included, so we democratized the learning. We had it be multilingual so everybody could participate in the language they feel the most comfortable in.

What do you hope for your child’s relationship with their culture?

My child is Pala-pino—he’s a child of the world. I hope he knows all facets of himself, because that’s what makes us whole—to know our roots, to know our lineage, to know our origin stories. I hope my child is a feminist child. I hope he lives in a world where racism and patriarchy are not the norm, but the exception. That he’s multicultural, and that his Arab identity is just as special as all the other identities it intersects with. I hope he knows the foods of his grandparents and likes them.

I just hope he doesn’t feel lost or as estranged as I did. I hope he feels proud and he’s able to carry that to the generation after him.

Photos courtesy of Arabiyya: Recipes from the Life of an Arab in Diaspora by Reem Assil, copyright © 2022. Published by Ten Speed Press, an imprint of Penguin Random House. Photographs copyright © 2022 by Alanna Hale

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.