Olot is a town about thirty-six miles inland from the Mediterranean Sea and a two-hour drive from Barcelona; but as far as Fina Puigdevall is concerned, it may as well be on another planet. A chef her entire life, she was born in the very house—masia, in Catalan—in which her two-Michelin-starred restaurant, Les Cols, operates today. The restaurant opened in 1990, and since then it has garnered international attention—although Puigdevall prefers to keep a low profile. She sticks close to home to do what she knows and loves: cooking food that represents the region she calls home.

Olot is in La Garrotxa, an area of Catalonia that houses a natural park with twenty lava flows, the Santa Margarida volcano, and forty formerly active volcanic cones that once gushed basaltic lava. Geologists estimate the area became volcanically active seven hundred thousand years ago, with the last eruption occurring eleven thousand five hundred years ago. Today, the rich, fertile soil marked with basaltic rock has spurned a cooking movement called cuina volcànica (volcanic cuisine) that has its roots in Olot and is based on exclusively using products grown and made within the volcanic zone. In particular, the region is celebrated for its goat cheese by the same name, buckwheat, endives, chestnuts, river trout, potatoes, Santa Pau beans, truffles, charcuterie, tomatoes, beef, suckling lamb, and ratafia—a sweet, viscous herbal liqueur often enjoyed as a digestif.

Les Cols is renowned in the region for adhering to a strict sourcing philosophy Puigdevall developed known as Kilometer 0 cooking. Most of what ends up on the plate at the restaurant comes from its two gardens and stables—either the one on-site or at Puigdevall’s current home, ten kilometers down the road in the rural village Vall de Bianya. Other products that can’t be sourced there are brought in from local producers. And despite La Garrotxa’s relative proximity to the sea, the only seafood diners will encounter comes from El Fluvià, the river that bisects both the volcanic zone and Olot.

I’ve noticed a special energy during my many visits to Olot and La Garrotxa over the years. The drive from other, larger cities in Catalonia is a climb into the past. As the minutes wear on, the many medieval stone villages become less frequent and more dramatic, like in Castellfollit de la Roca where the whole town is perched on a sheer jagged basalt outcropping. Finally, the A-26 highway crosses El Fluvià and descends into a small valley where the green hills become old volcanoes and the gateway to the Pyrenees truly begins.

There are other manifestations of the valley’s feeling, particularly in its forest, La Fageda de Jordà—which was named for famed Catalan poet Joan Maragall. It’s populated with beech trees only grown on the Iberian Peninsula due to its specific microclimate and volcanic soil. Olot is more humid than any other town in the region—trapping moisture in between its mountains—and is the subject of a popular Catalan saying, Si no plou a Olot, no plou enlloc (If it’s not raining in Olot, it’s not raining anywhere). It seems cuina volcànica refers to much more than a cooking philosophy; it’s an attempt to harness the magic of La Garrotxa and coax it into something more tangible.

Fajol, or buckwheat, is an ingredient native to the area that has captured Puigdevall’s heart. “It was very popular before the civil war,” she tells me, referring to the Spanish Civil War. “But after the war, not as much. Nobody really eats it anymore, so I’m trying to bring it back.”

On the menu, fajol takes many shapes. Puigdevall’s cooking employs modern techniques—she studied at Ferran Adrià’s school for chefs at nearby elBulli—so each dish is a fresh spin on a classic Catalan dish and uses traditional Catalan ingredients. The grain first shows up during the amuse-bouche course, served in the masia’s grassy backyard while diners lounge on a stone wall. With cava to accompany, the wait staff sets down a slate with two small bites: the first is a cured pork sausage covered by a paper-thin layering of buckwheat. The second is a hot, soft pork sausage covered in a buckwheat dough; it is the most sophisticated take on the pig-in-a-blanket a diner could imagine.

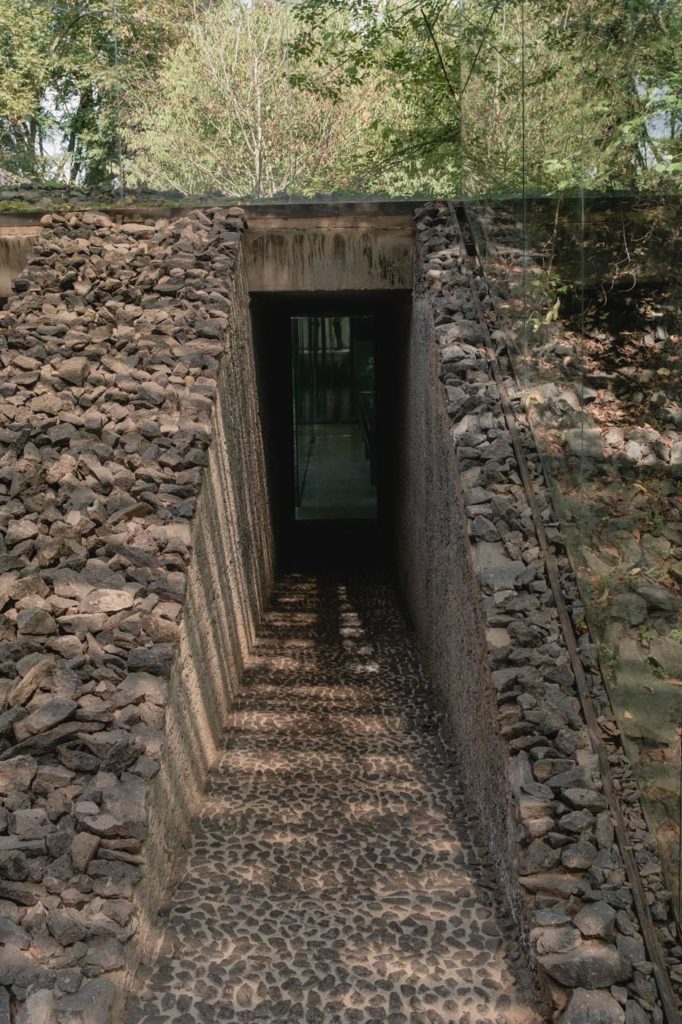

Afterwards, guests are led through a long, railroad-style room decked in gold metal and into a black, sleek and sparse dining room. Puigdevall and her team designed the futuristic metal tables and chairs. They also designed the restaurant, along with the five-room hotel by the same name operated by her family on the top floor of the masia. The whole operation won a Pritzker Prize—a prestigious international award that celebrates the best in architecture and design—in 2017.

The dining room tables look out onto the garden where Puigdevall’s chickens, ducks and other animals graze while diners progress through various courses. Two menus are on offer. The first is a fully vegetarian proposal made solely of ingredients from the Les Cols gardens. The second is a seasonal menu that offers the diner a few meat courses. For both iterations, the meal is as local as it gets.

Fajol returns to the menu in the form of a single long noodle coiled in a smoked vegetable broth. It’s a simple dish, and it is deceptively delicious and intense. Other menu highlights include a frozen goat cheese yogurt with anchovy and basil oil; a shockingly simple and perfectly sweet beet purée with crème fraîche; local bolets, a type of mushroom, laden with pork fat; and Santa Pau beans, served with nothing but a bit of pork broth in a plain white bowl.

I first visited Les Cols three years ago, and the memory of the experience lingers. This follow-up meal crystallizes exactly why. The food is simple, sublime and represents its origin, making for an emotional experience. My husband’s ancestral home is in Olot, and after we dine at Les Cols we would make the trip back to my mother-in-law’s home, where I’m a foreigner—looking to connect with a family with whom I don’t fully share a language. Having experienced Puigdevall’s food and understanding its intensely local roots, it gives me greater insight into the word I have become a part of by marriage.

I suspect Puigdevall knows the intensity of that feeling of seeking connection as well—perhaps it’s why she stays with her family, her restaurant, and the house in which she was born. Outside her world, things are rapidly changing. Catalonia is in the middle of a fierce struggle for independence, the effects of Spain’s lingering financial crisis continue to divide the country, and the very borders of the European Union threaten to disappear. But within the boundaries of La Garrotxa, the volcanic soil will continue to produce savory Santa Pau beans, tangy La Garrotxa cheese, perfectly acidic tomatoes, and slightly sweet buckwheat. And for as long as she’s able, Puigdevall will be there, making exquisite use of what her region has given to her.

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.