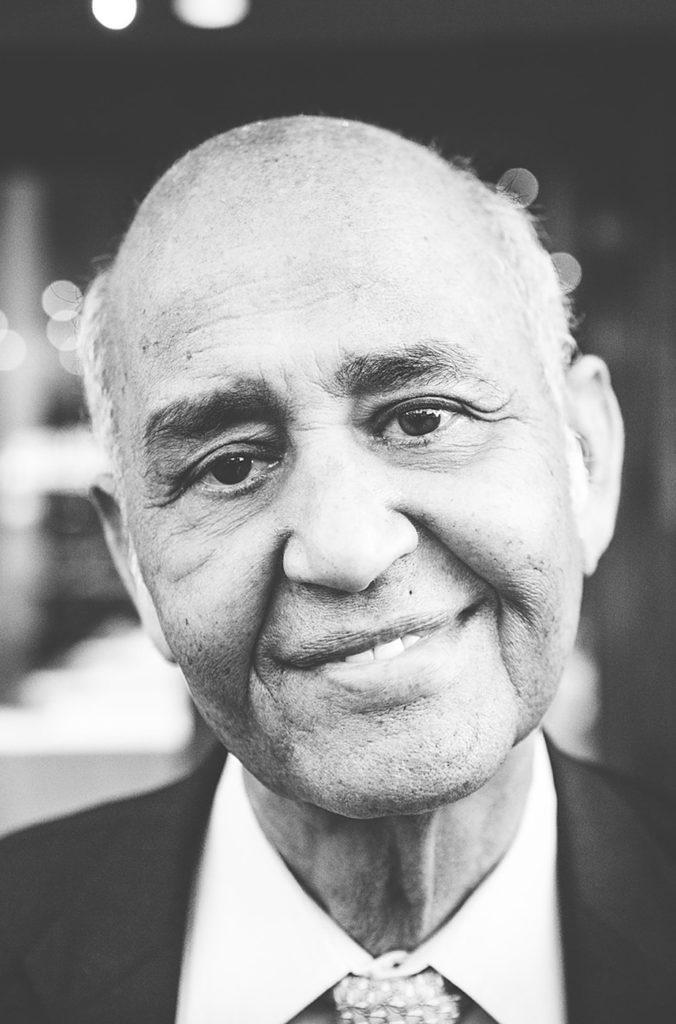

The Afghan-born San Diego restaurateur sitting across from me has a vivid image of his homeland in his mind. As a wiry man of 75 years, he carries himself with the air of a diplomat, tempered by a rare, modest humility. He remembers a country rich in culture and natural beauty, a resourceful people marked by kindness and hospitality, and a stable government ruled by a monarchy—a place he once called home.

Ziaullah Nasery was born into a highly esteemed family in Kabul, Afghanistan, his father a physician and his uncle a general commander of the nation’s military. An ambitious young man, he joined the military after high school and then worked in law enforcement throughout Germany and Austria, including INTERPOL. After several years abroad, he returned to his native land as the head of the DEA, a position that proved only temporary as the 40-year monarchy was suddenly overthrown in 1973 by a Soviet-backed coup. Nasery was imprisoned along with the educated elite for being anti-communist and released months later on house arrest. He seized the opportunity and escaped with his wife and children to Pakistan, then India, and finally Germany.

His wife Angela was also from a prestigious family. Her father worked closely with the king and her uncle was chief justice. When she and Nasery wed, both the kings of Iran and Afghanistan were present, with the Afghan princess drawing their ceremonial henna tattoos. It was her cousin, the Afghan Ambassador to the United States, who sponsored them to emigrate to the U.S. in 1982. “We came as immigrants,” Nasery states, noting the technicality, “but we are all refugees—all of us.”

While on the East Coast, Nasery applied to the FBI. With years of experience, a list of degrees, and fluency in five languages—he was labeled overqualified. Left with little in the way of options, and a dislike for the harsh winters, he and his wife took a whirlwind trip around the U.S. to find the best place to settle their family of four. They chose what Nasery refers to as “the greatest city in the greatest country in the world”—San Diego, California. Although they had been acculturated to the West through their years in Europe, it was a struggle to adapt to American customs, societal norms and dress. Having come from a conservative Muslim nation, they were visually assaulted by the scantily clad masses—something Nasery has never gotten used to. Frustrations continued to mount as he searched for work, and even more so when his friends suggested he open a restaurant, of all things.

Cooking had never been more than a hobby for Nasery, although he had become quite adept at it. It was during his first stint in Germany that he realized his appreciation for his own country’s cuisine. “My grandmother was always cooking excellent food,” he says with a smile. “I was used to that kind of gourmet, homemade food. When I went to Germany, I didn’t like it.” Following his first year abroad, he made a trip home and spent the entire month in his family’s kitchen. Having done all he could to learn the essentials, as well as the crucial art of Afghan rice, he spent the subsequent years in his own small kitchen perfecting it all.

Despite his initial reluctance, Nasery opened Khyber Pass in 1984 as the first Afghan restaurant in Southern California. When he speaks of the restaurant’s opening, his tone lacks the usual sense of pride in such an accomplishment. Although years of success trail closely behind, having started with a hole-in-the-wall taco shop turned Afghan food, to his current establishment in Hillcrest, there is still disappointment in his eyes. The restaurant was not a dream realized, but the manifestation of an educated Afghan’s struggle in a country that would not recognize his achievements. It represents years of 16-hour workdays, the labor so grueling he was often too tired to return home. The symbol of the lifestyle that was a far cry from the one he’d lived in Afghanistan. “My father was a physician,” he explains. “We had a big house… people working for us, cooking for us, a gardener, a driver, et cetera. When I was with the enforcement agency, I had four to five bodyguards, a driver and so on.”

“Then all of a sudden there is this big change, to come as a refugee to this nation, and start from scratch,” he continues. “It’s not easy, it’s not easy at all.”

When he speaks of the American people, however, his face brightens. He attributes the comfortable life he’s been able to build for his family, to the welcoming spirit of Americans, and to his loyal patrons. In the early days, when Nasery was doing all of the cooking and his wife working the front of the house, a customer asked to see the kitchen. Upon entering the shabby space equipped with just two small burners, he immediately wrote Nasery a check for a dishwasher. Although initially insulted by the gesture, his wife convinced him that it was meant as a gift. In 2000, he moved to his current location in Hillcrest since business had been struggling on Convoy Street due to the changing demographics of the area. “One customer gave me a very large check to buy this restaurant,” he recalls with profound gratitude. “A Jewish family that knows I am Muslim.”

The restaurant opened its doors and was met with immediate success—a line wrapping around the block every evening. There was no way Nasery could have predicted the events that would take place just one year later on September 11. Pointing to the empty chairs beside him, he recounts one incident. “There was a couple sitting there, and I was with them. Channel 8 was here, and one guy passing by yelled at my customers saying, ‘Shame on you for eating in this place—look at what happened!’” The customers responded in defense of Nasery, and that was the end of it. Besides a handful of vile phone calls, there were no other issues. In the end, he was deeply touched by the overwhelming support from the surrounding community. “I thought for sure we were done and would have to close down,” he confesses. “But the greatest month of business was after 9/11. The people in this area are so intelligent and sophisticated, they supported us and told others that we were those who had escaped our country, who had come here homeless, that it was not our fault, and we were not involved in these things.”

A plate is passed between us, disrupting our eye contact, and I’m drawn back to the present. I blink with eyes wide as I realize I’ve neglected the generous spread before me. Gesturing with his hands Nasery urges me, “Please, eat, eat. Afghan food does not taste good cold.” The disparate dishes crowding the table seem like a strange compilation of food from across the globe. There appears to be kabobs set atop Indian naan, kormas paired with Middle Eastern rice, Greek salad, and Asian dumplings topped with peas and a drizzle of yogurt. Sensing my confusion, Nasery shoots me a wide grin and says, “We have a variety of food.” A variety that seems haphazard without a proper introduction to Afghanistan’s history.

The mountainous country rests on a plot of land along the historic Silk Road, a meeting place for diverse peoples traveling from all over Asia, the Middle East, and Europe. Its coveted location is evidenced by numerous invasions throughout history by the likes of Alexander the Great and Genghis Khan, as well as the British, Persians, and Arabs, among others. And when the Soviets took over Central and Northern Asia, Afghanistan was consequently flooded with retreating Uzbeks, Tajiks and Turkmens. All of these peoples and nations have played an integral role in shaping the country’s cuisine as we know it today.

The crowning glory of an Afghan meal is basmati rice—with more variations than one could imagine. It’s similar to what you would find in the Middle East, spiced with saffron, turmeric and coriander, but its flavors are more potent and aromatic, and it’s often adorned with nuts and fruit. With such attention to complex rice dishes, their kormas are subtler, as if in efforts to keep from overwhelming the senses. Less rich than in India and only moderately spicy, they serve as an addition to the rice, often made with beef or lamb kofta (meatballs), and even kidney beans. Pastas like ashak and mantu are akin to dumplings, an obvious influence from Central Asia, and served with spiced meat which can be attributed to Persia. I mix and match mouth-watering bites of it all, amazed at how the flavors from such differing nations could be so masterfully blended and balanced into one cohesive meal. The people of this land have taken a history of war and upheaval, and created a beautiful mosaic—Afghan cuisine.

“We have seen every part of life. What is dark, what is bright, what is good, what is bad—everything.”

——

Nasery not only labored with all of his might to stand on his own, but he’s supported countless others in doing so too. “This country was built by refugees,” he declares, “and is so successful because of the immigrants and refugees who come here.” The majority of his staff is Afghan, with most having been with him 10 to 20 years. His current head chef, Qais Farmuly, is from Kabul, and was formally trained there before coming to the U.S. Nasery is still present in the restaurant most days of the week, throwing an apron on over a suit and tie—which he wears every day. But it is Farmuly who has been carrying more of the load the last couple years.

As we stand at the bar just outside the kitchen, close enough for Farmuly to run in and check on things as needed, he recalls his memorable first encounter with Nasery. The interview was set for 4 p.m. sharp and when he arrived, Nasery immediately directed him to the kitchen to help cook for the impending dinner rush. Despite much protest at being completely unprepared for such a task, Nasery persisted—gentle, yet unrelenting—and Farmuly was by his side moments later. “I’ve been here ever since,” he says with a chuckle.

While Farmuly is thankful for the opportunity to do what he loves, there is this beautiful reciprocity between the two, as Nasery feels incredibly grateful for him as well. “Without him, I would be dead,” Nasery confesses. “Without him, this restaurant would be closed. If he left today, tomorrow it would be closed, honest to God.”

With his country’s turbulent history at the forefront of his mind, Nasery reflects on his own arduous journey. “We are lucky,” he asserts. “We have seen every part of life. What is dark, what is bright, what is good, what is bad—everything.” He intimates some of the struggles of his friends who battled depression upon emigrating to the U.S., having lost everything. “I told them, ‘This is the reality today; what it was, is gone. There is no kingdom, there is no king, there is no power. We are all refugees, we are just ordinary people here… we should work hard to stand again.’”

——

Our ongoing column, Roots by L&T Contributors Nicole Bravo and Lauren di Matteo, explore lesser-known stories of those who take a traditional approach to food to honor their heritage or to rediscover those useful, time-tested methods. These stories hone in on the lineage, history and perpetuation of cultural customs—or even the clashing of those values with the fast-paced life much of the world embraces today.

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.