Puerto Rico — August 20, 2020

Puerto Rico’s Struggle for Agricultural Sovereignty

Despite decades of policies discouraging Puerto Ricans from farming their lands, local farmers and activists lead the move to reclaim local agriculture in the face of crisis.

By Paola Nagovitch

Photography by Carlos Corral

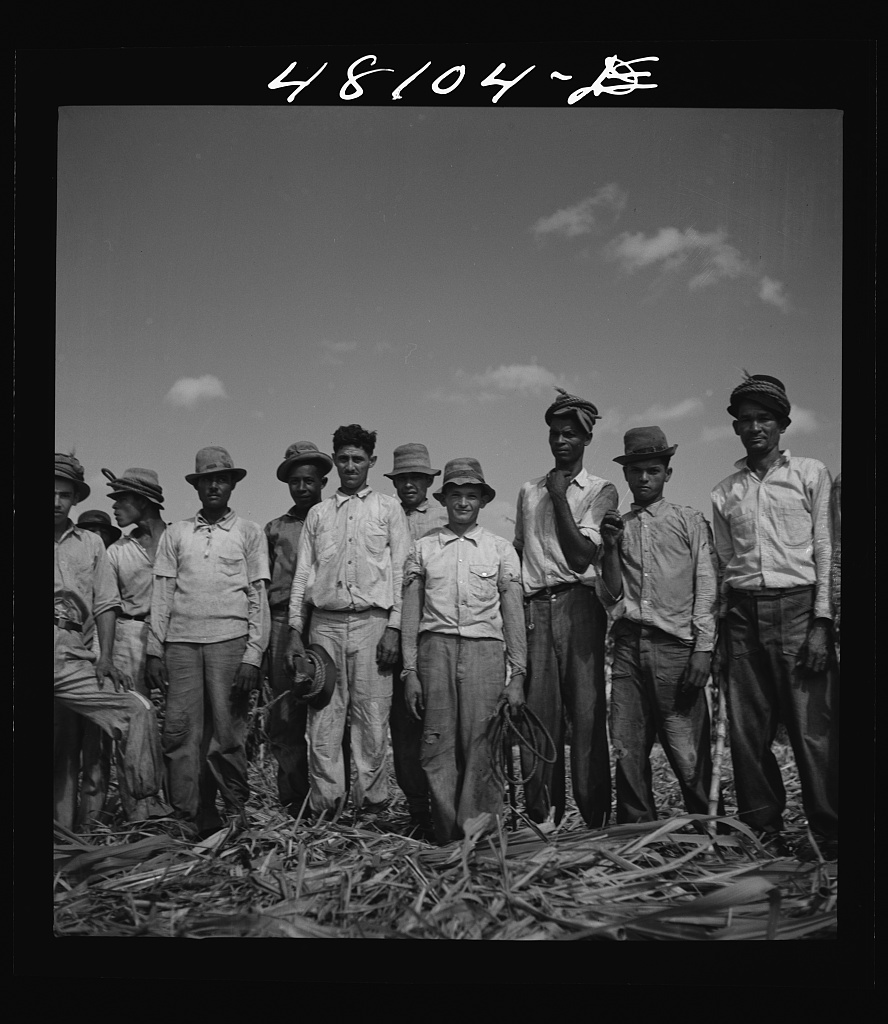

Those of us who grew up in Puerto Rico were raised with the image of the hard-working and humble el jíbaro puertorriqueño—the farmers who have worked the island’s countryside since the nineteenth century. But where are those jíbaros now? And, most importantly, how can we look to their traditions as a way toward a more sustainable, agriculturally sovereign Puerto Rico?

The puzzle as to why Puerto Rico imports over eighty percent of the food it consumes lies in its current relationship with the United States. The island’s hesitation––and inability––to grow its own food is both a symptom of colonialism and a consequence of decades of policies discouraging the island from doing so.

David Rivera is one of the few farmers in Puerto Rico who specializes in growing pana, or breadfruit. Beyond his pana business, he is also the island’s primary turmeric producer. Through this speciality, the farmer based out of southwest Puerto Rico has carved out a relatively stable career as a local producer. Most of us on the island either fry pana into tostones or mash it to prepare mofongo, both of which are staple Puerto Rican dishes. Yet, despite produce such as pana being such a crucial part of Puerto Rican diet, Rivera estimates less than five percent of the food sold in supermarkets across the island is grown locally. “And that’s a bold estimate,” he adds.

But that wasn’t always the case. The difficulty Puerto Rican farmers face nowadays when they try to sell local produce didn’t become a reality until the island fell under Uncle Sam’s dominion. Although Puerto Rico was first colonized by the Spanish in the eighteenth century, most of what was consumed on the island under Spanish rule was produced locally. By the late 1890s, and right before the onset of the Spanish-American War, consumption of local produce on the island topped eighty-five percent, according to Rivera, who adds that what was imported at the time served merely to compliment what was grown locally.

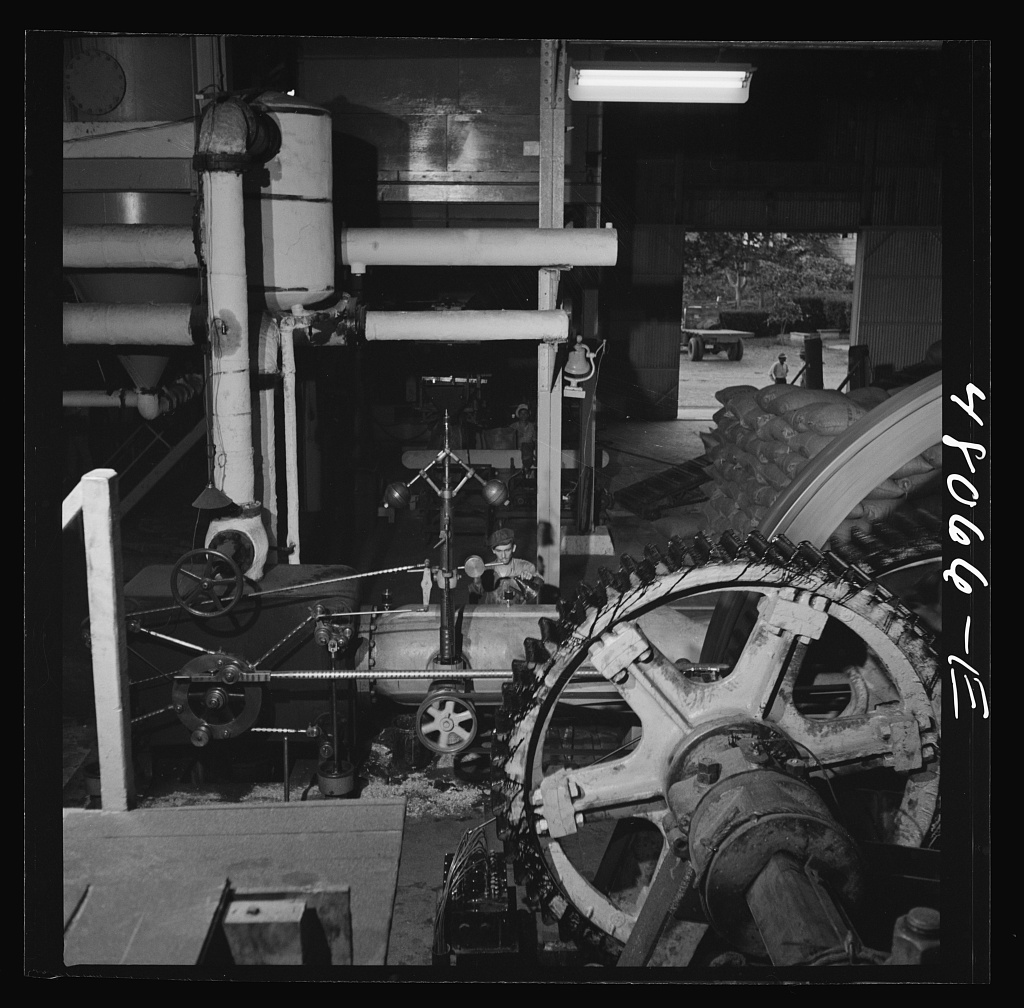

As sugar industries began to collapse across the Caribbean in the late nineteenth century, Puerto Rico emerged as a primary sugar producer in the region; and by 1890, the United States became the island’s loyal consumer. Upwards of sixty percent of Puerto Rican sugar exports were going to the United States by then, compared to around thirty percent going to Spain, which, at the time, controlled Puerto Rico. But the fate of the island’s thriving agricultural sector and sugar success story was sealed on July 25, 1898, when the United States landed in the southern shores of Guánica, Puerto Rico.

For Rivera, the United States was the primary force behind the abandonment of the island’s agricultural sector––a shift that still impacts his work, pushing him to invest in new strategies to thrive as a local producer. “I have the same problems as every other farmer in this country,” Rivera acknowledges. “But I am doing well as a farmer. Why? Because I am a pioneer.” Rivera has dedicated his career to trying new things with agriculture to guarantee himself a spot in the local market.

But Rivera also attributes his success to the culture he has cultivated on his farms. For the last fifteen to twenty years, he’s had the same group of people work on his lands. “These are people who have dedicated all their lives to agriculture,” he says, noting it’s hard to find that type of commitment and love for the land.

Back in the early twentieth century, the opposite was true. The United States understood the island’s potential for agricultural growth and invested in it. Upon arrival, “the United States fostered an economy in Puerto Rico based on three things: sugar cane, tobacco and coffee,” says Rivera. As a result, the island experienced a farming and development boom. Prosperous years followed and cash flowed as sugar production soon overtook the other two crops.

But in the 1930s, the sugar high came to a crashing halt, and it took the island’s farming business with it.

Cue Operation Bootstrap, a series of policies that began in the late 1940s sponsored by the island’s first elected governor, Luis Muñoz Marín, and backed by Congress in the mainland. The island’s legislature, in which Marín served as a senator from the Popular Democratic Party (PPD) before being elected to govern in 1949, passed the Industrial Incentives Act of 1947––officially launching Operación Manos a la Obra. The Act, which granted private companies a ten-year exemption on an array of taxes in order to incentivize them to set up shop on the island, was just the first step that solidified Puerto Rico’s shift away from agriculture to industrialization.

By the time the U.S. territory adopted its current political status of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico in 1952, an exodus was already taking place within the island as campesinos migrated away from the countryside. El jíbaro puertorriqueño were forced to abandon their lands and cram into urban centers in search of employment. In 1956, the total income generated by the manufacturing sector overtook that of the agricultural sector for the first time in the island’s history––a milestone that has not been overturned.

“In any part of the world where a country has abandoned its agricultural sector in exchange for industrialization––the country is doomed,” says Rivera. “When a country abandons its agriculture, it enslaves itself to countries that produce food. It’s that simple.”

On April 30 of this year, Giovanni Roberto led a protest in the island’s capital against the government’s handling of the Covid-19 pandemic. The protest, called Caravana por la Vida (Caravan for Life), ended with the local activist being arrested. Outrage flooded social media after a video showed Roberto being slammed against a car and taken away in handcuffs.

Hours later, Roberto was heard singing from his jail cell that all he wanted was to feed the poor: “Yo lo que quiero es comida pa’ los pobres.” Roberto was released from jail that night after a judge found no cause for his arrest.

The April caravan wasn’t Roberto’s first run-in with the authorities. Roberto has been an active leader in his community for at least a decade, from leading university strikes to working against rising food insecurity as conditions on the island continue to worsen. Puerto Rico is currently suffering from a crippling debt topping $74 billion and thirteen-year-old economic recession dating back to the financial crisis of 2008.

At the onset of the global financial crisis, unemployment in Puerto Rico hovered at around ten percent. Between 2010 and 2012, that rate spiked to seventeen percent, compared to the United States’ rate of nine percent. As a result, by 2012, the number of Puerto Ricans living in the mainland U.S. far surpassed the island’s entire population.

Despite the mass exodus and a tightening economic crisis, those who stayed behind succeeded in temporarily reviving the island’s neglected agricultural sector. Farm income grew by twenty-five percent between 2012 and 2014––totaling more than $900 million and creating over seven thousand jobs, according to data from the governor’s office. Alongside this farming boom, Comedores Sociales de Puerto Rico (Community Kitchens of Puerto Rico) emerged in 2013 as a local food distribution group with Roberto as its spokesman. The organization became an activism-centered initiative to address hunger on the island.

Unfortunately, those gains were short-lived. Hurricane Maria struck Puerto Rico in September 2017, destroying the island’s electrical grid, killing thousands, and wiping eighty percent of the island’s crops. But if you’ve heard anything about la isla del encanto, it’s that we’re a resilient people. Post-Maria Puerto Rico was no exception, and a local food revolution started to take hold once again after food scarcity as a result of the storm laid bare the dangers of relying on imports and not growing enough local food.

Recalling an “accelerated” spike in food insecurity since Maria, Roberto explains, “hunger has not returned to the point that it was before 2017. And now with Covid––this is a disaster.”

Covid-19 docked in Puerto Rico in early March after two cruise passengers and a local man tested positive. Governor Wanda Vázquez immediately placed the island on a stringent lockdown, instituting a curfew that has now been in place for more even still as cases top twenty-eight thousand with more than three hundred and fifty deaths. Just like that, the island is once again facing a new crisis coupled with the island’s colonial status, its economic crisis, and the local government’s mismanagement.

Still, the move to reclaim Puerto Rico’s agriculture and jíbaro practices continues to emerge out of the necessity, in the face of disasters and emergencies, to sustain ourselves and survive. The Organización Boricuá de Agricultura Ecológica, an internationally-renowned farming and activism organization on the island that promotes food sovereignty and environmental conservation, has spent the last thirty years working to identify, nurture, and support the jíbaro who live within every Puerto Rican, says the organization’s general coordinator Jésus Vázquez.

“That identity exists within all of us,” says Vázquez when I asked him whether the jíbaro identity was still present in Puerto Rico. “That is who we are.”

Both Organización Boricuá and Comedores Sociales are working toward a healthy and sustainable Puerto Rico built on the values of our jíbaros. Recognizing the importance of local produce, Comedores Sociales even hopes to launch their own agricultural project in the near future as the organization continues to expand to address the island’s hunger.

But farmers across the island need institutional help. Puerto Rican farmers no longer receive a subsidy since the government scrapped the law in 2018 after being in effect for more than thirty years. The subsidy was replaced by an incentive based on production––a system that the legislature is now considering reverting after it proved insufficient. To make matters worse, an investigation by Puerto Rico’s Center for Investigative Journalism found that as of May of this year, the island only had 5,439 acres of public land available for leasing and farming; 2,544 of which couldn’t be rented because of their condition.

“Producing food under our historical context is hacer patria,” says Vázquez, evoking a common phrase on the island and the Puerto Rican diaspora that relates to protecting, defending and helping the homeland. “But there’s a need for greater support, and for that there’s a need for greater political will.”

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.