Editor’s note: This story was originally published in Issue One of Life & Thyme.

——

I can’t remember how many times I’ve been here. Or how many times my bare feet have been jolted awake with each step on this pristine, cold, white marble. Or how many times I have been awestruck at seeing this golden vision in front of me, seemingly floating on water. I can’t remember how many times, but I can remember every detail, every sensory experience. And on this brisk December day, as the last shreds of morning fog linger over me, I will be adding to my memories of this heavenly place.

Literally meaning the “House of God,” the Harmandir Sahib—known to many as the Golden Temple—is the embodiment of human acceptance and tolerance. Located in the city of Amritsar, Punjab (founded in 1574 by the fourth Sikh guru, Guru Ram Das Ji), the holiest of Sikh shrines was completed in 1604 by Guru Arjan Dev Ji, the fifth Sikh guru. Four doorways—one for each direction—lead into the gurdwara (place of worship), welcoming all regardless of religion, caste or creed. Sikhism was founded by Guru Nanak Dev Ji—the first of ten Sikh gurus—in the Punjab region of northern India. Strongly rejecting the notion of caste, the world’s fifth largest religion places sharing, community, inclusiveness, and oneness at the core of its values. One can witness these tenets in full effect at the Harmandir Sahib.

The spiritual presence, tranquility, and beauty of the Golden Temple are what most visitors remember. However, there are extraordinary acts of humility taking place behind-the-scenes every day. Coined by many as the world’s largest free eatery, the mass scale of food production, cleanliness, and efficiency found inside the Golden Temple’s kitchen is mindboggling. Langar (a common kitchen where food is served inside of a gurdwara) was initiated by Guru Nanak Dev Ji, and then implemented by Guru Amar Das Ji—the third Sikh guru—as an institution designed to uphold the equality between all people. All gurdwaras serve langar and anyone can eat for free. But the enormity of the Golden Temple langar is unparalleled.

Standing inside the main work area, I take in all that is happening around me. Huge swaths of garlic lay on the floor, blending into the white marble. Pea pods are camouflaged on green carpet. Men, women, and children, all with heads covered and feet bare, are working with purpose, peeling garlic and plucking peas. Mammoth cauldrons, some topped up with lentils and vegetables and others waiting to be filled, statuesquely sit atop equally giant gas burners. In another area, men and women sit at individual stations, rolling out discs of dough to be cooked on a loh (large flat-top iron grill). Men are rapidly flipping roti (unleavened Indian flat bread), filling metal tub after metal tub. There’s also a roti-making machine that cuts, flattens, and cooks bread automatically in order to keep up with the sheer volume of daily consumption.

On average, one hundred thousand visitors partake of free, hot, vegetarian meals daily at the Golden Temple. Double that number on special occasions and holidays. What does a grocery list look like to feed that many people? Here’s a breakdown: ten thousand kilograms wheat flour, twenty-five hundred kilograms lentils, one thousand kilograms rice, five thousand litres milk, one thousand kilograms sugar, five hundred kilograms pure ghee, and one hundred gas cylinders are used daily. These essentials are both contributed by devotees and paid with donations received from visitors. The Harmandir Sahib kitchen runs around the clock, and relies on the hundreds of employees and anonymous sevadar (volunteers who selflessly work without looking for any payment, reward, or recognition) to prepare the meals. People of any religion can volunteer, and some have been humbly giving their time every day for years.

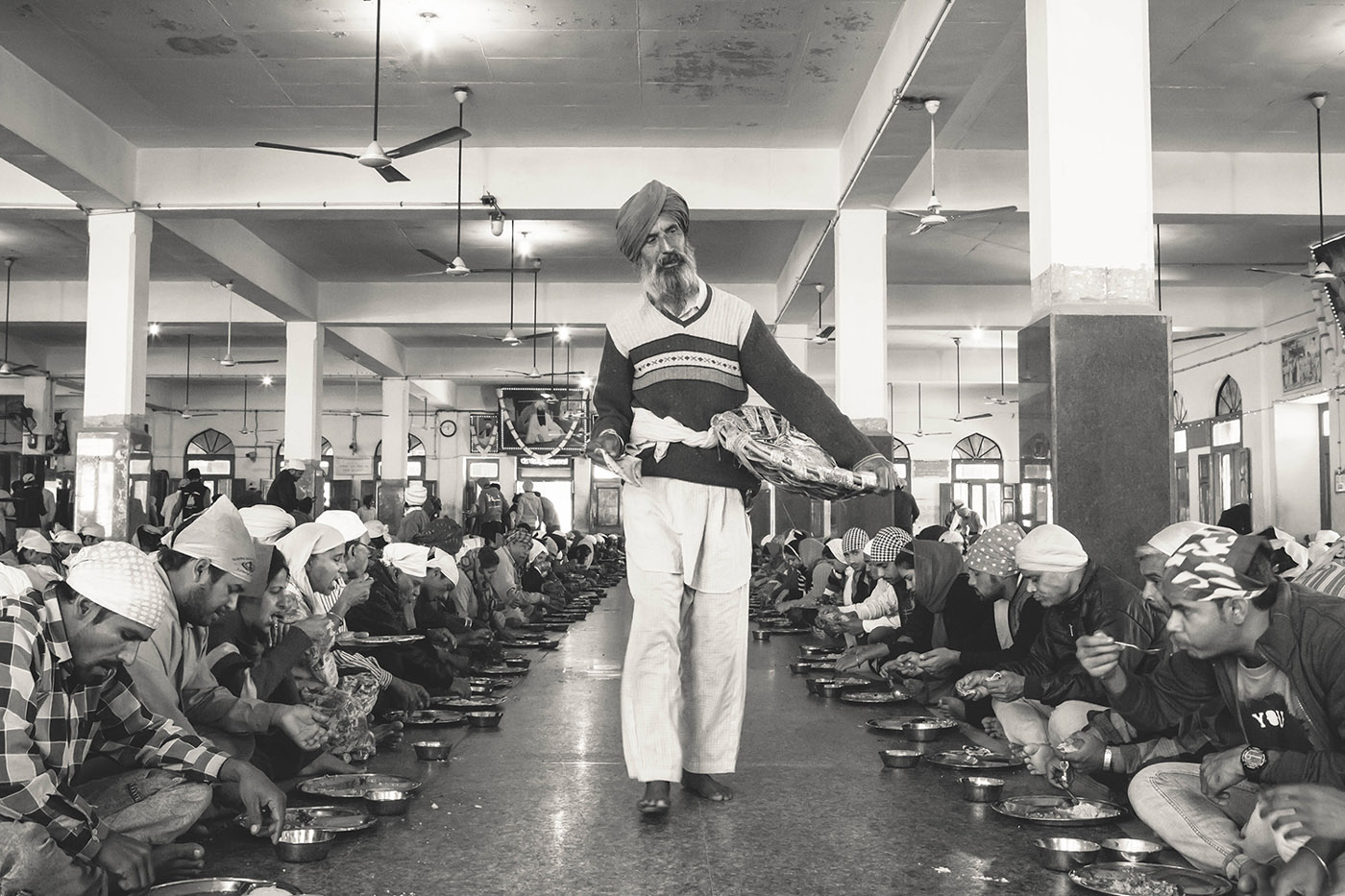

I follow a sevadar into one of the large communal eating rooms. Everyone sits on the floor in neat rows, legs crossed, on the same plane. No matter your social status or occupation, wealth or lack thereof, ideology or ethnicity, here, all of humanity dines as equals. Food is served multiple times by volunteers, and there is no restriction on how much one can eat. Vand Ke Chakna (sharing the fruits of one’s labor—be it wealth, food, etc.—with others in the community before considering oneself) is one of the three main pillars in the Sikh faith.

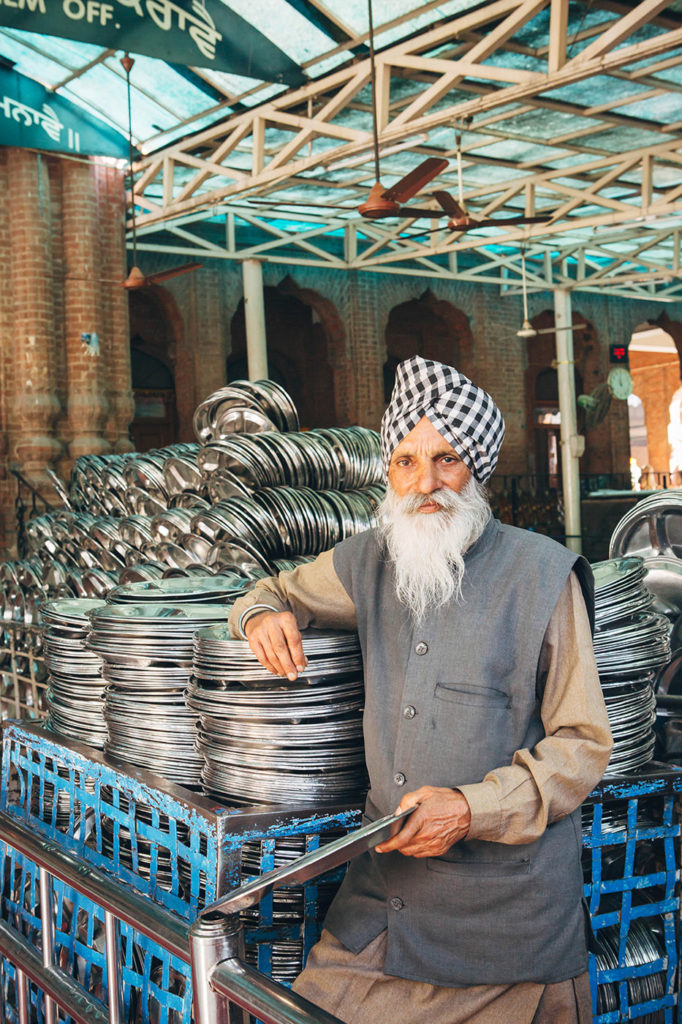

After guests finish eating, I follow them outside where they are greeted by a human chain: men standing side-by-side, passing dirty plates from the first person to the last. The items are emptied of any leftover contents before entering the washing stations. The clank, clank, clank of stainless steel plates, bowls, and spoons pounds into my ears. It is a symphony in its own right. Every dish and utensil is washed through five different stations by volunteers. The cycle repeats as clean plates, bowls, and spoons are stacked and stored, ready to be handed out to the next wave of incoming guests.

This visit to the Harmandir Sahib reminded me of man’s great capacity for compassion. In our daily lives, it’s very easy to forget the good in this world where “Love Thy Neighbor” seems more wishful thinking than reality. But everything I witnessed this December day reaffirmed my faith in humanity, humility, and service. These vivid memories will stay with me, no matter how many times I visit again.

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.