The Tortoise and the Hare, Aesop’s classic fable, is one many of us know by heart. It’s a cautionary tale of the brazen speedster and the quietly determined—a lesson in the best path to take, the way promised to win in the end.

As nostalgic as it is, and however mildly it may temper the morals of children, there’s a thread of Aesop’s tale woven in many modern industries; ironically, in a way that reveals its leaders aren’t always keen on emulating the winning turtle. Instead, today we see many rabbit-esque companies chasing bigger profit margins, better bottom lines, erasing any semblance of a finish line, and leaving disastrous humanitarian conditions in their wake.

We’ve already seen it with food. After years of deforestation, drive-thru meals and corporations lining grocery shelves, we’re connecting the dots. Cattle-ranching is leveling the rainforest. Obesity is rising at unprecedented levels. Cardiovascular disease is our leading killer, and it’s projected that nearly 50 percent of Americans have or will develop insulin-resistant Type II diabetes in their lifetime (at a cost of $322 billion a year). Because of these diet-related (and, sure, financially-related) implications, many of us sit down to the table differently now. Documentaries like Super Size Me, Farmageddon and Cooked have started a conversation on what we eat, how we eat, and where we buy our food. “Farm-to-table” isn’t the culinary subset it once was; the slow food movement is edging mainstream because our health and planet depend on it.

So the tortoise is back in the game.

Or is it?

While we don’t eat our clothes, maybe it would be helpful if we did. Maybe then we’d be quicker to connect those dots related to an even larger consumption problem, one beyond organic meats and veggies. If we’ve learned anything from the value of slower, more sustainable food, it’s that slower, more sustainable fashion is the next conversation waiting to be brought to the table. And it can’t wait for space much longer.

“I couldn’t understand why an industry that is forward-thinking and innovative in so many ways could be lagging behind in basic human rights and climate issues,” says Cora Hilts, co-founder of online sustainable fashion retailer Rêve En Vert. “I saw fashion as an opportunity, as a medium for change.”

Change we desperately need.

What most of us might not realize is there’s a system in place we’re not supposed to see. I didn’t see it, or really care about it, for a long time. In fact, considering that “fast fashion” has only been a phenomenon for the last two decades, and I’m now 31, I’ve no doubt contributed directly to its success. As a teenager, my room was littered with bright yellow shopping bags; in college, I happily bought cheap outfits on a whim. All the while I thought it couldn’t possibly be that bad. There was no way I was really contributing to a global crisis.

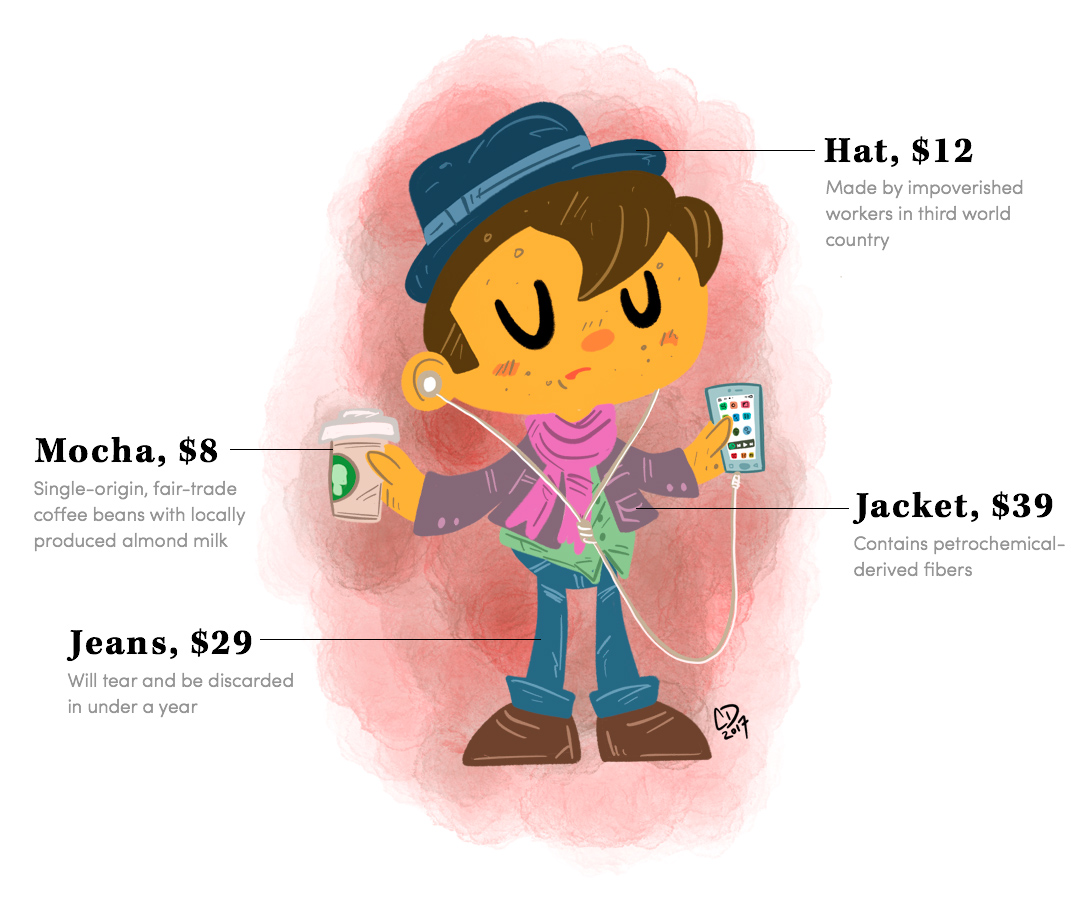

But as it turns out, a global crisis is exactly what we have. Since the late ‘90s we’ve consumed almost 400 percent more clothing, around 80 billion new pieces every year. In America, our purchases result in 11 billion tons of yearly textile waste alone, 60 percent of which is made with petrochemical-derived fibers that will take 20 or more years to decompose, leaving one to wonder what sort of soil will be left behind once they do?

As the dots come into focus, it’s clear why fashion is the world’s second highest polluting industry after oil. With repeat purchasing patterns, many of us have just been playing the role it’s been assumed we’d play, but the blame isn’t solely on us. The larger burden rests with those rabbit-like machines, companies that see profit in under-regulated countries, spinning cheap fabric while leaking volatile compounds into the water supply. For example, since becoming home to several textile firms—where runway-copied designs are produced and shipped out by container to malls around the globe—Indonesia’s Upper Citarum River is now indistinguishable from a landfill, yet 35 million still use it to drink and bathe. This is the system, meant to stay hidden behind the latest racks before we have time to notice.

Although there are people who notice. People like Hilts, and she isn’t alone.

“We don’t think it’s necessarily a lack of empathy on the consumer’s part;” says Parker Clay founder Ian Bentley, “it’s on us to show the world what it looks like to be a part of the bigger story.”

Parker Clay, which employs farmers and artisans in Ethiopia to create high-quality, ethically-sourced leather goods, is one of a growing number of companies considered “slow fashion,” the enlightenment—if I may be so bold as to call it that—that happens when a company chooses to invent solutions versus merely fuel a need to consume. In the same way slow food has caught on, because we’re realizing we don’t eat in a vacuum and our meals have either positive or negative consequences, the same is true of our closets. Like food, clothing is a non-negotiable; it follows that we should increasingly think about how and from where we’re buying ours.

Today’s wave of purposeful fashion is geared toward the modern dresser. “This stigma that is often associated with ethical brands is what we are focused on changing with Nisolo,” says Zoe Cleary, Nisolo’s co-founder. “We hope that when consumers actually take a look at our product offerings and branding, that they will agree that our products can compete with many of the large scale brands. The reality is that scaling of ethical brands is what is required to make an impact on the fashion industry and scale starts with people believing in the product.”

One visit to Nisolo’s Nashville showroom immediately discredits the notion that “conscious” can’t also be beautiful. Velvet-soft leather slides, mules and Chukkas pop in neutral shades against clean white walls. It’s calm, simple, but also striking. These are products meant to go with anything, yet last through changing styles and seasons. More than believing in a good product, a shopper here can easily believe that this is the future of fashion—it has to be, because it’s creating futures that depend on it.

“To date, Nisolo has created 147 sustainable jobs in developing countries where stable employment and a steady income are hard to come by,” explains Patrick Woodyard, Nisolo’s co-founder. “More than half of our producers in Peru had never previously worked in the formal economy. Through working with us, producers have experienced an annual income increase of 140 percent, and women have felt the impact of a stable income to a greater extent, reporting an annual income increase of 173 percent!”

He continues, “Whereas the majority of our producers left school before they intended to due to financial reasons, 100 percent of our producers’ children are in school. Thirteen percent of them are studying at university, and all of them will be first time university graduates in their families.”

It’s the same with Parker Clay, where community is central to commerce. Employment opportunities are scarce for young women in Ethiopia, and many are exploited in prostitution or domestic service as a result.

“We love talking about Zewditu, one of the first women to join our team,” says Bentley, who explains how Zewditu was facing the same grim job prospects. “This is when she came into the Parker Clay story, where we offered her a job after training to sew. She has been an incredible part of our team and when you ask her what she dreams of, she talks about getting married and having kids and family of her own. She says this with the biggest smile on her face, and frankly, this is why we do what we do. We measure our success through stories like these.”

And these stories are where we catch a glimmer—the hope—that maybe the future can be different, that maybe the gap of disparity in the wake of fast-fashion won’t get wider, but instead circle back to where consumer demand solves the world’s needs. If fast-food giants like McDonald’s can now claim they source sustainable beef and chicken without antibiotics, maybe it’s not a stretch to think big box stores could follow suit. What will it take?

“Consumers. Consumers need to take their time with shopping, learn about brands, find out where products, materials, and labor are coming from, tell others about great sustainable companies they have found, and do research about where their money is going,” Bentley says.

Hilts agrees. That’s why she started Rêve En Vert, to make it easy for consumers to feel good about where their money goes and at the same time, find products they love readily available online. “We never want REV customers to sacrifice style for ethics, but we equally want them to be able to learn why and how to buy more consciously,” she explains. “Success for us is when someone is able to purchase an item they love for its look just as much as it’s story.”

As great as this sounds, there’s one last barrier to slow fashion: price. Its cost on the backend is clear, paid out through cheap material, poor working conditions, and environmental disregard. But what about on the front end? How is someone on a budget realistically going to afford a $200 ethically-made sweater when a $40 one at the mall will do in the moment?

Isn’t slow fashion, sort of, extravagant?

“One consistent complaint I hear about sustainable businesses are the prices. Yes, they are more expensive, but you get what you pay for. The $10 shirt you find at the mall won’t last more than several wears,” says Hanna Baror-Padilla, founder of Los Angeles-based Sotela. She started her dress line to provide wardrobe staples that can adapt to a woman’s body, without the need for a customer to buy multiple items.

And with that, she hits the fulcrum of fast-fashion: It thrives on its ability to keep us in lack. Think of it this way: There’s no denying bad food tastes good. Oil, salt and sugar are magic ingredients to make a less-than-nourishing meal still taste delicious—and keep us addicted so that we keep coming back for more. The same premise exists in the form of flashy advertising and shoddy workmanship. Fast-fashion needs you to believe you and your closet aren’t full. Why have one, really good sweater that’s made with quality materials when you can have five or six sweaters, but on the cheap?

In an industry primed to make us feel dissatisfied, slow fashion actually does the opposite. It might challenge us to spend more but in doing so, to also buy less. When we do that, we can starve off the instant gratification of a quick purchase, instead saving and reconnecting with our money so the money we do spend equally serves us (and the world) right back.

Slow fashion, ultimately, is a matter of the heart. It’s a matter of sensing the value we have and how it can be used to bring about real change. As Hilts points out, “I think empowerment is the top reason for people to shop sustainably. At a time when the world is feeling a bit chaotic, the ability for people to vote with their wallets is so powerful. Every purchase we make is a vote for the sort of business we want to see, and whether this is shopping at a local farmer’s market or buying ethically-made fashion, we as individuals have the ability to influence markets.”

If we return to Aesop once more, then we see how napping Hare woke up because he heard the crowds cheering for Tortoise as he crossed the finish line first. We may not be in the race, but that doesn’t mean we lack the power to change its course.

——

References:

1. “The Hare & the Tortoise.” Library of Congress Aesop Fables. N.p., n.d. Web. 25 Feb. 2017.

2. Glatter, MD Robert. “Half Of Adults In The U.S. Have Diabetes Or Pre-Diabetes, Study Finds.” Forbes. Forbes Magazine, 09 Sept. 2015. Web. 25 Feb. 2017.

3. EcoWatch. “Fast Fashion is the Second Dirtiest Industry in the World…” Eco Watch, 17 Aug. 2015. Web. 25 Feb. 2017.

4. “Environmental Impact | The True Cost | Learn More.” The True Cost. N.p., n.d. Web. 25 Feb. 2017.

5. “Fast Fashion.” Ethical Marketing and the New Consumer (2015): 215-27. Web. 25 Feb. 2017.

6. “The Environmental Scourge of Indonesia’s Textile Boom.” Undark. N.p., n.d. Web. 26 Feb. 2017.

7. “Polluting Paradise.” Poisoning Paradise. N.p., n.d. Web. 26 Feb. 2017.

8. “Synthetic Fabrics Made From Fossil Fuels Are Worse Than You Think: Fiber Watch.” EcoSalon. N.p., 13 May 2014. Web. 25 Feb. 2017.

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.