My fascination with cookbooks began when my mom gave me a copy of Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse Cookbook: Favorite Recipes from Mickey and His Friends when I was six years old. Through food, I would get closer to my favorite characters. Tinker Bell’s Spaghetti Sauce? I loved spaghetti too! Cinderella’s Grilled Cheese Sandwich? Yes, please! Bambi’s Garden Salad, Pluto’s Hot Dogs, and Mickey’s Sugar Cookies were a few of my other favorites. (Unbeknownst to me at the time, Peter Pan’s Pasta and Caterpillar’s Corn on the Cob are quite possibly where I learned my love of alliteration.)

Although I graduated from Mickey long ago, it was at that young age when my voracious appetite for cookbooks—and for reading in general—began. But it wasn’t until many years later that I started to make the connection between food and history. Most recently, I’ve spent countless hours perusing the Huntington Library’s collection of rare cookbooks to gain a deeper understanding of history. Through the language of food, cookbooks give us insight into a culture and a time period that bring us way beyond a recipe, ingredient or trend; they add personal insight—“personal” because we each have our own relationship with food.

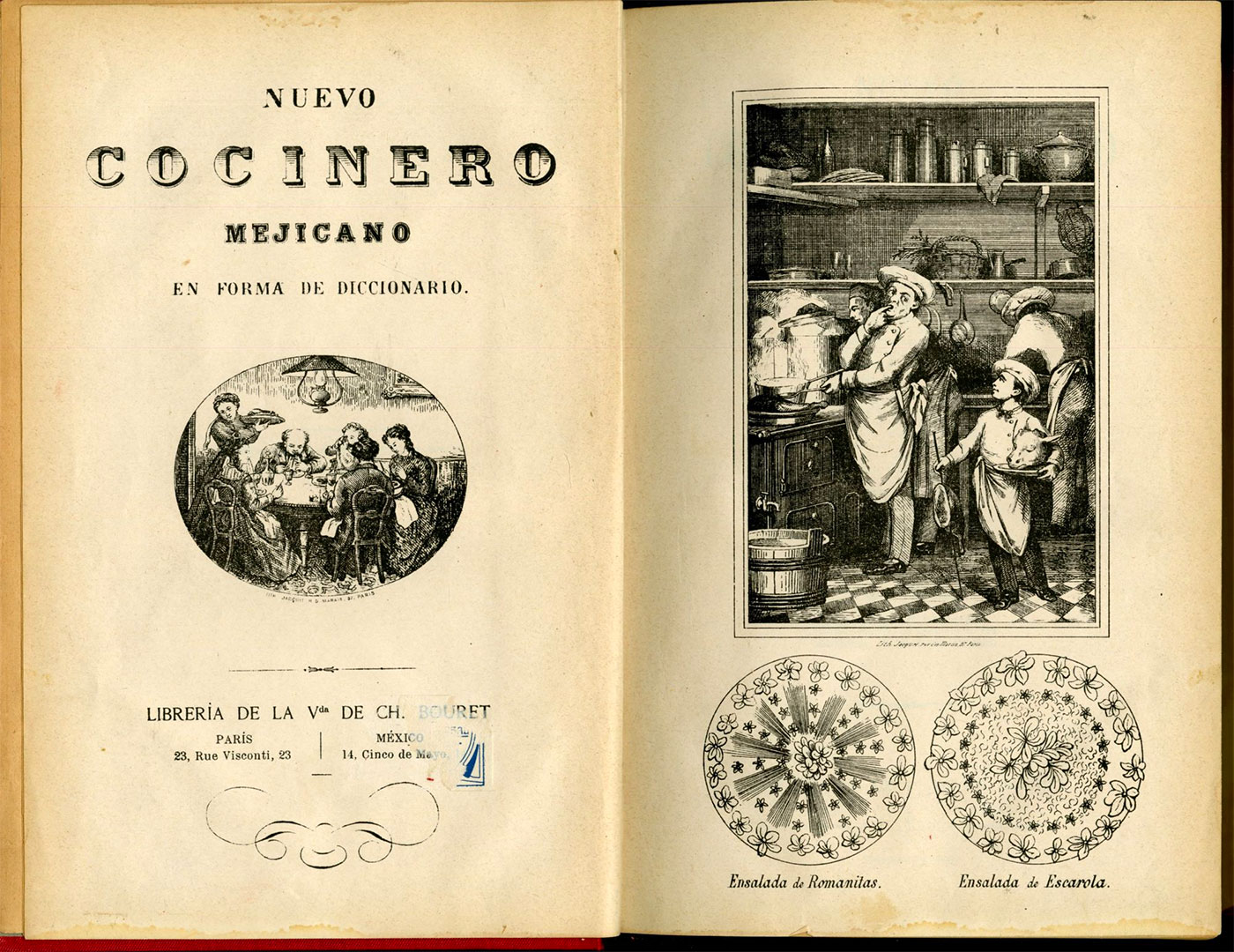

One such cookbook, and the subject of my most recent obsession, is Mexico’s first, El Cocinero Mexicano (The Mexican Cook), published in 1831. Yes, the first Mexican cookbook doesn’t appear until the nineteenth century. Crazy to think, given the fact that the roots of Mexican food go back way beyond modernity. The reason for this involves colonialism, politics and identity.

Here’s a smidgen of history.

There is evidence that maize (corn), the life force of the Americas, has been domesticated in Mexico for over ten thousand years. The Aztecs grew over 760 species of squash. Dozens of bean varieties added protein to their diets. Mexico is also responsible for introducing the world to chocolate, which was cultivated as a spicy and frothy drink for Mayan and Aztec nobility, as well as the delectable vanilla, avocados (gasp goes the hipster nibbling on her avocado toast), tomatoes (hard to imagine Italian food without them), and chiles (Thai food without heat would seem lacking), to name only a few.

Then came the Spanish conquest (1519-1521), which changed everything. At the time of the conquest, the Aztec Empire was at its height. Its military and economic power extended from the Pacific Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico and Guatemala. Emperor Montezuma (1466-1520) ruled from the capital of Tenochtitlan (today, downtown Mexico City)—one of the largest cities in the world, with several hundred thousand people and another million or so in the surrounding cities.

No cookbooks were written during pre-colonial and colonial times, but culinary observations were documented in the diaries of missionaries post conquest. The most notable of these is Historia General de las Cosas de Nueva España (General History of the Things of New Spain), more commonly known as the Florentine Codex, by Fray Bernardino de Sahagún (1499-1590). Regarded as the father of ethnography and one of the first culinary historians, he began collecting material on the Aztecs from native informants and recording their culture in Spanish, Nahuatl (the Aztec language) and Latin. The anonymous men who wrote and illustrated the codex incorporated themselves into a newly globalized world, all without losing their own cultural identity. Along with entries on science, religion, philosophy and natural history, they give us exhaustive lists illustrating food and dining habits in sixteenth century Mexico. They mention eating crab tamales in green chile sauce, and lobster with tomato sauce.

In sixteenth century Mexico, for the first time in history, ingredients from throughout the world met, in essence creating the original fusion cuisine. European settlers introduced livestock, rice, wheat, exotic fruits, sugar and other ingredients, herbs and spices as well as cooking techniques that had already made their way to Spain under Moorish rule (711-1492). These early settlers preferred European foods, particularly wheat bread and meat, but they acquired a taste for many indigenous foods, including beans, chiles and chocolate. This cultural mixture is so complex that at times it is hard to tell exactly where particular traditions originated (I was surprised to learn that cilantro is native to the Mediterranean, mangoes and bananas are from India, and limes come from East Asia).

Between that early clash of cultures and the time when El Cocinero Mexicano (The Mexican Cook) was published, the native people were forcibly converted to Christianity and became second-class citizens in their own country. Food became a divider of classes. Corn, which for millennia had been thought of as a life force with many religious connotations, was considered inferior to wheat, the body of Christ. Bread became an “uptown” food; tortillas were for society’s lower echelon. Avocados were considered the “poor man’s butter” and not something consumed by gente decente (decent people). There was a perception that the more European you were, the closer to the top of the social and racial hierarchy you belonged. New World ingredients gained higher ground when combined with or prepared like those from the Old World. Mexican food was becoming a mestizo mash-up of sorts.

By 1821, Mexico had gained its independence from Spain and the first wave of French immigrants arrived in the country with new recipes and techniques promoting a wave of la comida afrancesada, or French-style cooking. Mexico began to spread its wings and assert itself as a country with an identity of its own—an identity with three centuries of cultural mixing.

Then—boom—a decade after Mexican Independence appears El Cocinero Mexicano, the book that set the tone for Mexico’s national cuisine and that would become the most influential Mexican cookbook of the nineteenth century. Published by Mariano Galván Rivera, the anonymous author quotes Alexander Dumas’ Dictionary of Cuisine importance of stocks as a foundation of cooking but surprisingly makes little mention of tamales, enchiladas or quesadillas. The recipe for tortilla in the book is not the corn variety but the Spanish potato omelette. You do see twenty different recipes for mole (the Nahuatl word for sauce is mole, and when you think about it, texturally speaking, it is a creamy sauce akin to many of the French sauces). Many recipes of The Mexican Cook apply French techniques to the preparation of Mexican ingredients. The native squash blossoms, huitlacoche (corn fungus) and avocados took beautifully to French style soups, crepes and mousses. A new national cuisine was born which blended indigenous, Spanish, and French ingredients, traditions,and techniques. How’s that for authentic?

Given Mexico’s long and complex history, the formation of Mexican culture has largely been viewed in European terms. Reading between the lines of The Mexican Cook, we understand the culture and the attitude of the Mexican elites toward their own culture. A missing enchilada recipe doesn’t necessarily mean they weren’t eaten, it’s just that native servants wouldn’t need instructions for making them.

The cookbook was reprinted a dozen times throughout the nineteenth century. Frida Kahlo, who was born during the wake of the Mexican Revolution of 1910, owned a copy. This Eurocentric view eventually reversed itself and nationalistic pride emerged post Revolution. That said, up until relatively recently, upscale food in Mexico was European, and Mexican food in the U.S. was seen as either a weird Tex-Mex hybrid cuisine, or cheap immigrant food consumed standing next to a truck.

Luckily this is changing and Mexican food has become exalted to the status it deserves. Chefs around the world, from Enrique Olvera of Pujol in Mexico City and Cosme in New York City to Gabriela Cámara of Cala in San Francisco and Carlos Salgado of Taco María in Costa Mesa are sharing its complexity with the world and building bridges between time, people, countries and communities while they’re at it.

Anne Willan so simply and eloquently says, cookbooks can lead us to “the world beyond the hearth.” Sitting in front of a plate of Mickey’s Sugar Cookies, I wholeheartedly agree.

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.