From the ![]() Sweets Issue

Sweets Issue

Buttermilk rusks—the hard, dry, slightly sweet, twice-baked South African biscuits (cookies to Americans)—are supreme dunkers. To me, dipping a rusk into a mug of hot tea is a weekend morning, I’m-not-gonna-leave-this-bed-for-a-while ritual. And like all good rituals, this one calls for mindfulness. Losing focus leads to over-dunking, and the ensuing finger-scalding efforts to fish out an overly softened piece of rusk flotsam.

A rusk is worth this sacrifice. And while I’m dipping mine, so are thousands of other South Africans, all partaking in this messy shared national ritual.

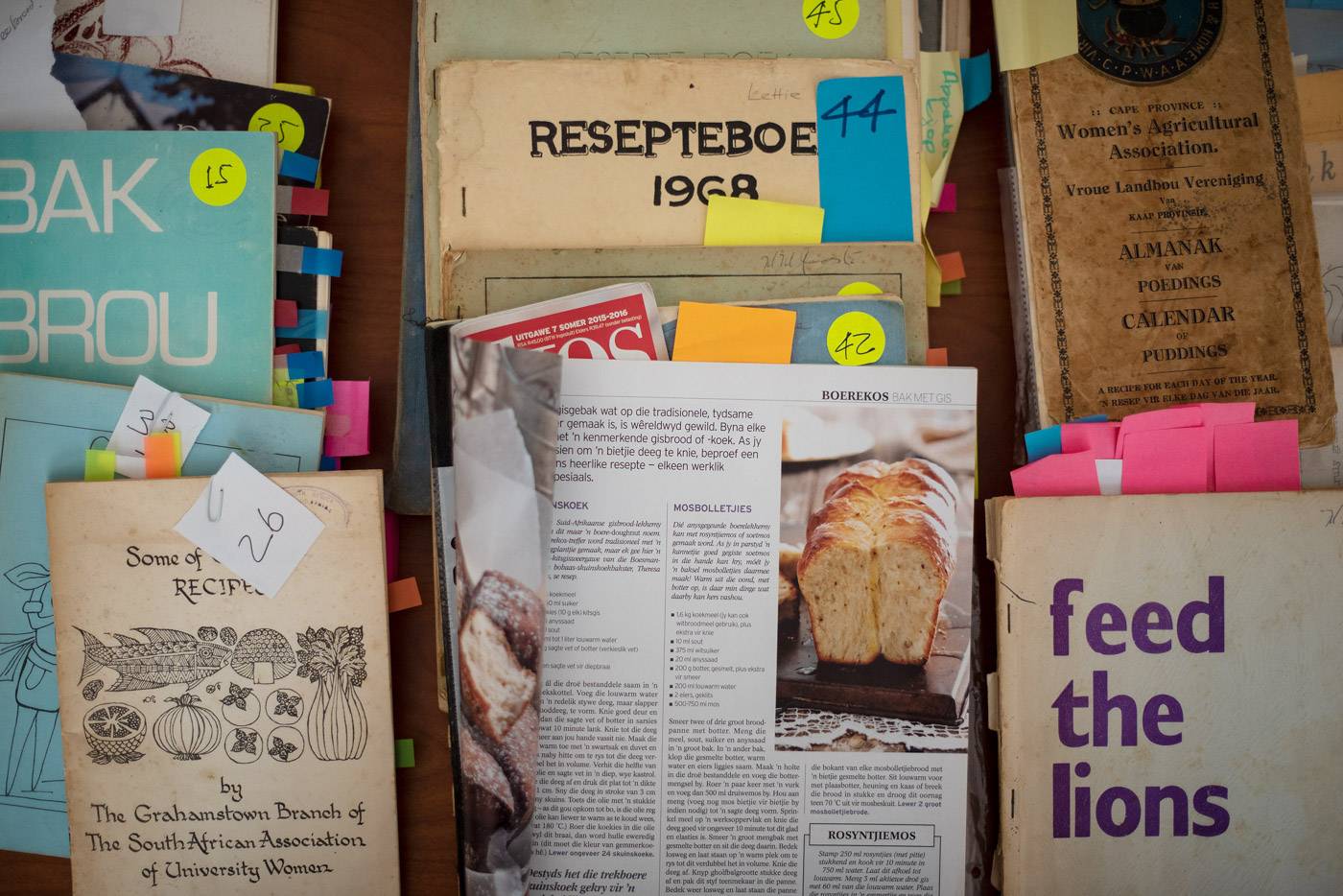

“The mission of a rusk is to be dipped,” says Errieda du Toit, a well-known South African writer and researcher currently working on a text about community cookbooks. Out of the ten national dishes she’s selected for her book, karringmelk (buttermilk) rusks are number one. Rusks could be compared to biscotti, but they are, in fact, only distant cousins.

The family of rusks has evolved from early Cape settlement staple to Afrikaans coffee-mate to today’s iconic national bake, and has brought my photographer colleague Claire and I to du Toit’s suburban Cape Town home—this and a rusk master class with Daleen van der Merwe, a retired cookbook and food magazine editor and instructor.

Van der Merwe starts each morning with a homemade rusk. Her everyday rusk is what she calls a “health buttermilk rusk,” the ubiquitous rusk that most South Africans eat today. “It’s been a practice on farms in the Cape to break the fast at day break with mosbeskuit and black coffee, dipping it into the coffee,” du Toit explains. “Similar to the French, with their croissant and coffee.”

South African rusks originated in the Cape Colony, settled by the Dutch East Indies Company as a way-station along the Spice Route in the mid-1600s. “The word beskuit [Afrikaans for biscuit] has its roots in the French biscuit de guerre—an extremely hard, close to inedible rusk of flour and water,” explains du Toit. The etymology reflects an admiration for French culture. “[Locals] took on the French word for rusk rather than their own ‘tweebak’ (literally, ‘twice-bake’). The Dutch brought the term biscuit and the skill to make them to the Cape. Biscuit became beschuit, and later beskuit.”

But the French brought the finesse. Specifically, French Huguenots, who brought winemaking to South Africa, and with it, grape must: the flavorful mash of juice, seeds and stems. Fermented must became the rising agent for rusks.

“The first rusks in the early days of the Cape settlement were made with hops, and the quality of the baking was considered excellent, especially when the settlers started growing their own wheat and became self-sufficient,” says du Toit. “Vast amounts of beskuit were made and bartered with the fleets. They liberated sailors from the terrible dry, hard biscuits they were used to.” Demand for Cape-made biscuits exploded, and a legacy was born.

Over the generations, the family of rusks continued to evolve. “The unsweetened boerbeskuit were made by taking some bread dough and adding to it ingredients like kaiings (pork crackling), raisins, fennel, and anise seeds,” says du Toit. “These weren’t made into balls like mosbeskuit, but rather marked into blocks with a buttered knife in a pan. When they came out of the oven, the pieces were broken off, put back in the dying embers of the oven, and left overnight to dry out,” says du Toit. “The biggest regret in my life was I never asked my mother to show me how she made boerbeskuit. If you’re twelve or twenty-one, what would make you think that one day you’d want to make this? By the time I wanted to taste them again, she’d stopped making them.”

Rusks remained an Afrikaans-only staple until the twentieth century. “After the second World War, many Afrikaners moved to cities, and beskuit migrated with them,” says du Toit. “Afrikaans food culture became part of city life, and Afrikaners began mixing with their English neighbors.” By then, karringmelk rusks had become the norm, with buttermilk always at hand on farms. With no overnight rise required, they were also quicker to make.

In 1939, the commercialization of rusks began when Ouma (Grandma) Greyvenstein from Molteno—a small Eastern Cape town—used a little start-up money from the local pastor to bake her beskuit on a larger scale. By 1941, she’d set up a small factory, which eventually became Ouma Rusks. Now part of a national food corporation, the brand is entrenched in national culture. Which is not to say home cooks don’t make rusks anymore. “Even in our busy lives, people feel they can still make time to make karringmelk beskuit,” says du Toit.

“In the family of rusks, the mosbeskuit and soetbeskuit are the upper echelon—the rusks with a university education,” says du Toit. She continues that their refinement, thanks to added sweetness, “gives them that little bit of luxury to temper the very harsh conditions on a farm—like having cake for breakfast.”

For our lesson, van der Merwe makes sweet rusks—or soetbeskuit—South Africa’s heritage rusk. These are the second generation of rusks: the children of the first mosbeskuit, made from a yeast-risen egg-enriched bread dough that got its rise from fermented grape must. She starts by making a sponge with active yeast, lukewarm water and milk, sugar and flour, and lovingly covers it with a baking cloth. It normally ferments for about an hour. In our case, with the 105˚F degree heat outside, it’s shorter.

She grates cold butter against a floured grater (so it won’t stick) into a mixture of cake and bread flour, then makes a well and pours in the bubbly well-fermented sponge, lemon juice and egg. “The art of making beskuit lies in very, very thorough kneading,” van der Merwe says, but her hands really tell the story. Minutes later, she points to du Toit’s countertop mixer with a smile; it cuts a few more minutes off the knead time. We cover the dough and leave it to rise for what should be six to eight hours (or overnight, preferably). Conveniently, she’s brought pre-risen dough for the next stage.

It’s quite the process, which is why few cooks still make these most traditional rusks, and those who do make them in enormous batches. Normally, van der Merwe bakes them only once a year for the December holidays. It’s no surprise that few bakers today attempt soetbeskuit. What would be considered a major cooking project today was once a regular activity on farms, where on the weekly bakdag (baking day), rusks and other breads were baked in huge quantities.

Another knead, another rise, and then the delightful pinching off of cute little dough balls (bolletjie) with buttered hands, which are then packed closely together and brushed with more butter in a greased bread pan, tilted up at an angle so the bolletjie will snuggle up as they rise again before their first bake.

Our conversation stops when van der Merwe pulls the billowing loaf of soetbeskuit out of the oven to brush the top with a sugar glaze. We wait a few minutes and she turns the bolletjie-crowned loaf out of the pan. It’s pure baking drama. We begin pulling the bolletjies apart into rusks, with the characteristic “feathers,” or flakes, of the warm bread stretching as we slather a few hunks with soft butter.

These are the rusks I adore. Mine are usually store-bought, but they are simple to make; you just need time—hours in fact. A mixture of butter, buttermilk, flour, sugar, and your choice of additions is patted into a baking pan, scored with a knife, and baked. Rusks are broken into fingers and dried again in the oven. “A rusk is like a chameleon that can become anything,” du Toit says as we discuss the possible additions: muesli, bran, seeds, raisins, coconut. I like mine crammed with additions. Maybe that’s just the American in me.

Recipe

Daleen van der Merwe’s Buttermilk Rusks

Yields 60 rusks

Ingredients:

- 1 lb. butter, melted

- 2 cups buttermilk

- 2 eggs, beaten

- 2 lb. plain or bran-rich self-rising flour

- 3 tablespoons baking powder

- 1 ½ cups soft brown sugar

- 1 ½ cups muesli

- 1 cup oats

- ½ cup sunflower or pumpkin seeds

- ½ cup almond flakes

- Generous pinch of salt

These are the rusks I dream of. While quicker to make than traditional soetbeskuit, you should bake these on a day when you’re home for the long haul, as the second bake (when the rusks dry out) takes at least four hours. To this basic recipe, you can add seeds and nuts of your choice, coconut, extra bran, raisins, or other chopped dried fruit.

Method:

Preheat the oven to 350˚F. Grease two 9” by 12” oven roasting pans.

Let the melted butter cool down slightly, then add the buttermilk and eggs and beat together.

Mix dry ingredients well and add the butter mixture. Stir with a wooden spoon to mix well.

Scoop the mixture into the roasting pans. Press the dough into the pans evenly. With a knife, score the surface of the dough in each pan into 20 fingers.

Bake for 30 to 40 minutes, or until golden brown. Cool in the pans for about 10 minutes before turning out onto a cooling rack. When cooled completely, cut into fingers (using the marked lines as a guide).

Arrange on baking sheets and dry out in the oven at 190˚F to 210˚F (90 to 100 °C). Use a large spoon to prop the oven door open slightly. This allows the moisture to evaporate and will speed up the drying process. If dried this way, the rusks should take about four hours.

Store rusks in airtight containers.

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.