April 9, 2019

The Parsi Sweet Tooth

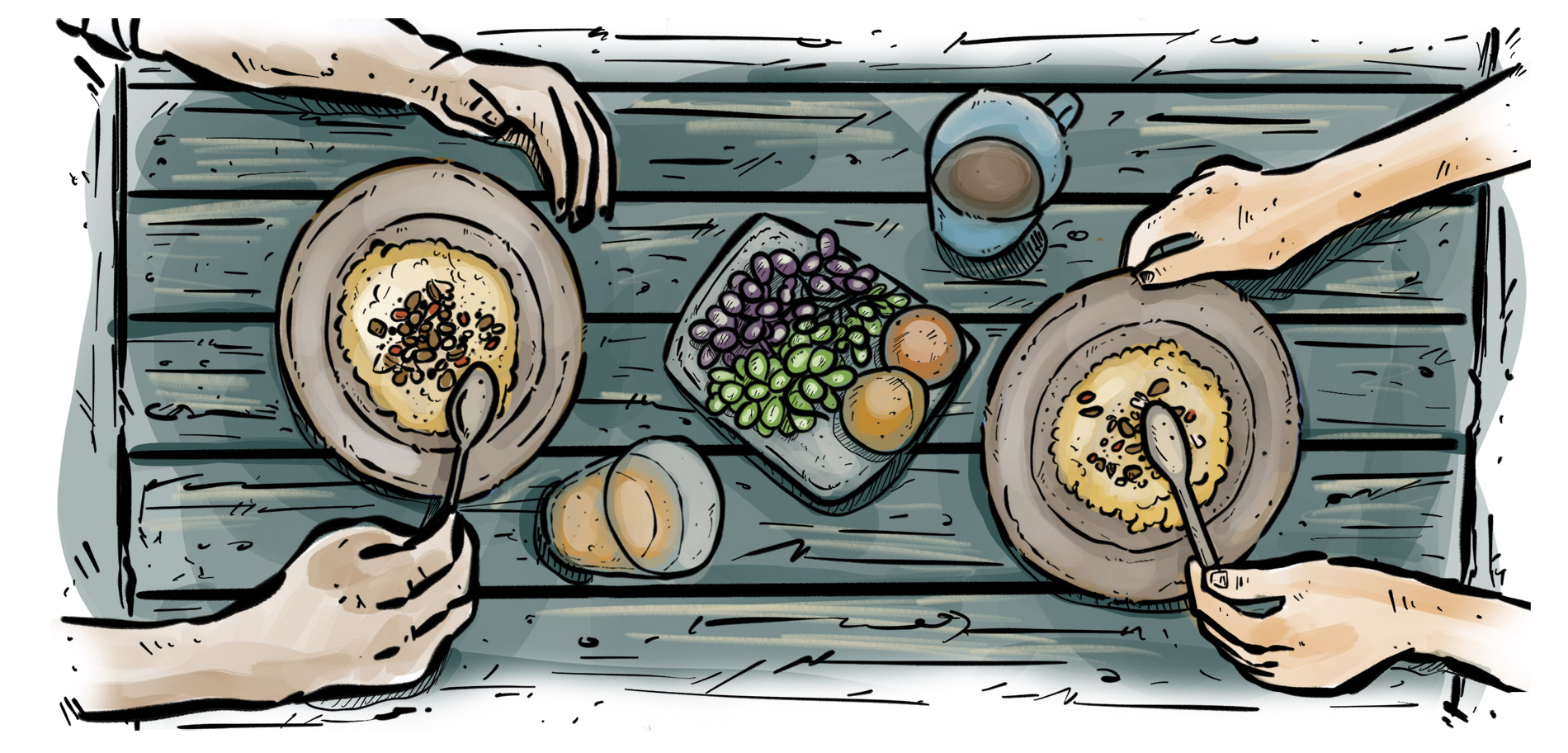

The Parsi sweet tooth has yielded countless dishes—both original and reworkings—including this recipe for ravo, a sweetened pudding.

Words by Meher Mirza

Illustration by Cesar Diaz

Many years ago, my elderly uncle was invited to a grand party, overflowing with friends and family and food. There were mutton patties and sandwiches, fried chicken wrapped in a lacy batter, semolina crisps, sweets shaped into the form of fish, kulfi and cake, a very sticky fudge called chikat halvo, and plenty of the fortifying draughts of Bacchus. My uncle, a jocular man of venerable age, was invited by the organisers to open the event with a brief speech. Silence fell. Preparing to deliver the discourse in his usual jolly, ringing voice, he clambered ponderously onto the stage, opened his mouth to speak and found that his false teeth were gummed together by the sticky halvo he had just eaten. As the audience waited with bated breath, inspiration struck. Swivelling his eyes round the gathering, he grandly blessed the audience with his hands, then slunk offstage after his wordless benediction.

My uncle was resourceful, yes, but more pertinent to this story, he was also a Parsi (a community known for their bon vivants). Before I continue, I’ll explain who they are. In the seventh century, the Persians (of Zoroastrian origin) were driven out of Iran by Arab invaders. At this time, the Muslim conquerors imposed their religion upon their subjects and the few who dared to disobey could resort only to flight. A small group furled across the ocean in storm-tossed boats, until they found refuge in the western Indian state of Gujarat. They came to be known as Parsis, fanning out into Mumbai and Kolkata, where they contributed immensely to the tapestry of India’s cultural and economic landscape.

Naturally, Parsi food is also born of crossed borders. Its taproots are found in pre-Muslim Iran (a predilection for dried fruits and nuts, rose water, pomegranate, saffron, and love of sweet-and-sour meat dishes), but it is equally beholden to Indian cooking. Parsi cooking has much in common with Gujarati flavors, but equally owes its fealty to Konkan, Goa, British food, even the Dutch thanks to their pre-British settlements in Gujarat.

Parsi Puddings from Here and There

Many of our homemade celebratory sweets are born from quotidian ingredients—milk, butter, sugar, yogurt (curd), rice. What shifts their timbre to decadent are the Indian and Iranian extras—rose water, slivered almonds, raisins fried in butter, and sweet, tingly cinnamon.

So we have vermicelli simmered with butter, sugar, milk, rose water and nutmeg, transformed into a silky cream called sev; semolina boiled with creamy milk, sugared water, vanilla and butter into the porridge-like ravo; a wobble of homemade curd sweetened with sugar; rice puddings, cooked in full-cream milk and ghee, are lit by cinnamon, cardamom, rose water, with a lattice of raisins and almonds over the top. We make these on birthdays, for weddings, or new year (Navroze) mornings to fuel for a long day of celebration.

A popular Parsi wedding sweet is the kulfi, served as tiny discs, each folded into its individual wrapping paper. Its origins are said to date back to the Mughal emperors, who may have brought the iced treat to India from Kabul and Samarkand. Eminent Indian food historian, K.T. Achaya writes in A Historical Dictionary of Indian Food, “its preparation is described in the Ain-i-Akbari (A.D. 1590) as freezing a mass of khoa containing chopped pistachio nuts and the essence of kesar (saffron), in a metal cone, sealed with a plaster of wheat dough, a method followed to this day.”

Like kulfi, a welter of Parsi favorites share their ancestry with India’s many communities. The Muslim malai na khaja, for one, are cream pastries baptized in a sugared syrup, then lifted out quickly to hold their crispness. The baglu, my grandmother’s favorite, comes to us from the Gujarati city of Surat; it is “made of layers of puff pastry so light they resemble the soft down of the cygnet, which is called baglu,” writes Parsi food writer and chef Bhicoo Manekshaw. The flaky mahim no halvo (a semolina sweetmeat, named after a suburb of Mumbai) and the chikat halvo are the very same sticky sweet that was offered to my resourceful uncle. And then there is the Gujarati sutarfeni, a sort of candyfloss made from rice flour, and jalebi.

Colonialism and the Parsi Pudding

The Parsis, always a precariously miniscule community (we represent approximately one sixth of one percent of the total Indian population), found it expedient to negotiate with the dominant discourse of the time—colonialism—in part by “modernizing” their lifestyle, of which food was a dominant entity.

In true Parsi style, this involved hybridizing every dish we pilfered. The British, for instance, brought with them sweet, milky, eggy puddings. But the Parsis pilloried these traditional baked custards, freeing the pudding from its lackluster confines. Manekshaw writes about the Parsi custer that “is copied from the traditional baked custard and has put the original dish to shame with its richness and flavour.” Our rococo version, cooked with eggs, cream, and full-fat milk boiled down to its depths, is spangled with nutmeg, cardamom, rose water and charoli nuts. This dense custard, bearing almost no resemblance to its venerable ancestor, is the lagan nu custer (the translation is “the wedding custard”), and is always served as a square hunk at wedding receptions.

Similarly, my ancestors pinched soufflés, milk and water jellies fashioned in traditional molds and caramel custard. Not all renditions were successful, however. I remember a distant relative who insisted on feeding me custard with a shiver of skin (the kind that crusts over hot tea) running through it every time I visited.

Plain Parsi Puddings

And then there are some dishes that are quite our own.

Perhaps our most idiosyncratic sweetmeat is the vasanu (think Italian panforte) made from a roster of ingredients as long as my arm, including the resin of a tree, dried water chestnuts, lotus roots, and dill seeds. Preparing the dish is rather tortuous. Each winter, my grandmother gathered her sisters for the process of soaking, peeling, chopping and frying fistfuls of ingredients. All of which were then stirred, re-fried in ghee, and poured into a bath of bubbling sugar syrup, and stirred again for hours until it all collapsed into a fudge. This was a warming dish, and a brief breakfast salvation from the jowls of winter. Admittedly, life in Mumbai is entirely innocent of bitter cold, but in Gujarat, where the dish likely originated, temperatures have been known to sink to forty degrees Fahrenheit.

But there are others that thankfully call for fewer ingredients. Similarly, Indian larder ingredients such as gram flour, rice flour, eggs, pumpkin, and even dill and bottle gourd, are recast in starring roles, to create lush fudgy dishes such as eeda pak (made from twenty-five egg yolks), larvo (a conical sweet fashioned from sweetened gram flour, usually offered to women who have stretched seven months into their pregnancy), mawa ni boi, a fish-shaped sweet (Parsis believe fish brings extraordinary luck, abundance and fecundity), doughnut-y bhakras, kumas cake, pancake-like chaapats, and popatjee (fermented, deep-fried spheres of dough plunged into sugar syrup before serving).

This is also the malido, a musky sweetmeat, luxuriant in its use of sugar, eggs and ghee—a consecrated food (a sort of holy wafer for the Parsis perhaps). Like the vasanu, it required daunting amounts of effort to make. Rotis had to be rolled and tossed, shredded into tiny pieces, then pounded to a powder. The powder was then folded into the sugar syrup, with eggs and ghee, and stirred and stirred. The entire family was co-opted into the seemingly-endless stirring that the preparation of the dish entailed. But all the effort was worth it. My mother and her brothers recall my grandmother making a silken, sunshine-hued malido, aromatic and pliant as putty.

Nowadays—unlike in my grandmother’s era—fewer and fewer people want to spend time over a hot stove, and with the decline of large, joint families (especially in cities), there are fewer hands to pitch in. As a result, homemade versions of these sweets are on the wane. But not in our house, where the tradition still waxes strong. Here’s an easy recipe from our kitchen.

Recipe

Ravo

Ingredients:

- 2 pints milk

- 4 tbsp. sugar

- 4 tbsp. butter (room temperature)

- 2 tbsp. semolina

- 2 tbsp. cream

- ½ tsp. vanilla essence

- 1 tbsp. rose water (optional)

- Raisins and almonds to serve

Method:

Finely slice the almonds together with the raisins; lightly fry in butter. Set aside.

Boil milk, then add sugar, stirring constantly until it has melted into milk. Next, stir in butter. When that is completely incorporated, sprinkle the semolina over the surface and stir well. Keep stirring until the mixture thickens. Pour in cream, vanilla and (optional) rose water, then remove from fire. Cool slightly and pour into a glass serving bowl. Sprinkle on top with fried raisins and almonds.

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.