The Journey

Family vacations. The yearly pilgrimage we take with our loved ones to escape our morning commute/deadline-driven/bored-kids-on-summer-break/daily lives. It’s a time for exploration and learning—not only of new places, but of ourselves and our acceptance and understanding of new cultures (and of fellow family members).

Traveling with small kids for a week-long trip can break even the most patient of parents. Multiple runs to big box retailers, the need to accumulate a remedy for every possible ailment or an outfit for every possible weather pattern—it can drive any reasonably sane mom nuts. Murphy’s Law will prevail if you leave the Benadryl or Neosporin or extra packet of hand wipes at home—the only defense is acute preparation. By the time we are boarding our flight with happy, empty-bladdered, freshly-diapered, well-fed kids (and meticulously-packed suitcases), I feel like I couldn’t have timed this departure any better. And then the overhead speakers crackle and our pilot’s voice booms through my eardrums. Our flight to Kaua‘i has been delayed. Not once, but three times for a total of three and a half hours on an active runway. What was that again about Murphy’s Law?

The audible excitement of touching down in Hawai‘i sounded more like a collective sigh of relief from every parent on our flight. The fact that we couldn’t see much of anything on Kaua‘i during our midnight drive from Lihue airport to the resort on the north shore added to the muted response of completing our maiden voyage to this Pacific island. I’m the first out of our family to crack open my eyes the next morning. Slivers of morning light pierced through the room’s blackout curtains, the vision before me catches my breath. Sharp, grey peaks—so close they looked almost like theater props—cut into the vivid blue firmament. Palm trees backlit by the glorious Hawaiian sun swayed in the offshore breeze. Sunlight twinkled like diamonds on the Pacific’s surface, each wave a crisp white against an azure backdrop where sea blends into sky. I exhale. Yes. The chaos of travel was definitely worth it.

The Island Ethos

We slip into Hawaiian-mode almost immediately. The pace of life is consciously slower on the northern-most Hawaiian island; it feels like an endless summer on Kaua‘i. Cell phones spent more time indoors, laptops stayed powered off, watches didn’t matter much, and flip-flops were acceptable everywhere. There’s an expectation of tourists to obey this unspoken rule of slow living.

The Garden Isle, as Kaua‘i is known, is the oldest—six million years old—and most untouched of all the Hawaiian islands. Nature rules here, and her subjects are in constant admiration of her beauty. With an area of 562 square miles, the island has three shores accessible by car—north, east and south—which are dotted with sandy beaches, small towns, and surfers. The western seaboard is home to a naval test facility, as well as the stunning mountains of the Nā Pali coast, which can only be approached by helicopters, boats, or on foot via hiking trails. The inner part of the island, from west to east, is where you’ll find the magnificent, iron-rich Waimea Canyon—the Grand Canyon of the Pacific, as Mark Twain once dubbed it—and Mount Wai‘ale‘ale, the watershed of Kau‘i and fountainhead of all seven major rivers of the island. Blanketed in thick clouds on most days, Mount Wai‘ale‘ale is one of the wettest spots on Earth. The sheer lushness of Kau‘i makes you want to either grow something or consume something off a tree. So I immediately set out to do just that.

The Market

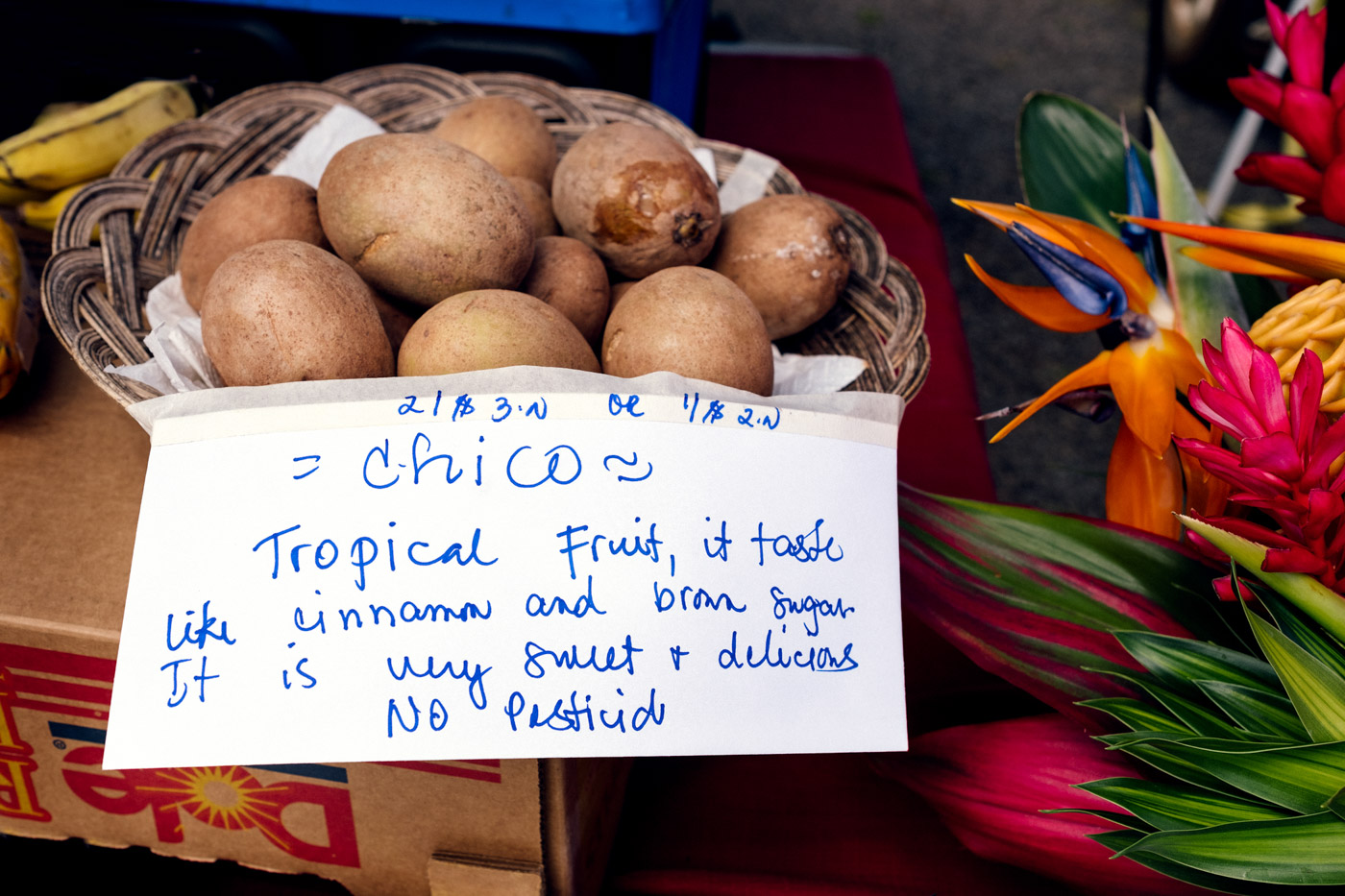

This impressive backdrop of mountains and prolific vegetation sets the stage for farmers and businesses to greet locals and tourists at the Saturday morning market in Hanalei—by far the prettiest I’ve ever visited. My first stop was to a young man with young coconuts. With deft machete skills, he lopped off shards of flesh, revealing a neat little hole in which he placed a straw. Refreshing beverage in hand, I made my way to each stall, taking in (and buying) all sorts of nature’s candy: pineapple, guava, papaya, mango, chico, cherimoya and star fruit, to name a few. Some local establishments were dishing out treats such as dark chocolate-covered bananas and Nutella-filled wontons. Locally-raised pork was topped with fried eggs and avocado for delicious breakfast sandwiches. There’s a warmth to this tight-knit community, a medley of native growers and transplant entrepreneurs from the mainland.

And behind the market, with an unobstructed view of the mountains, was a paddy of taro. Known as kalo in Hawaiian, taro is a root vegetable and the primary ingredient in poi, a staple in Hawaiian food that is eaten with salted fish and meat. Made by mashing the cooked plant stem and adding water, this pale purple starch dish can be consumed immediately for a sweeter, delicate flavor, or left for a few days to ferment naturally which creates a more sour taste. But to native Hawaiians, taro’s significance goes much deeper than simply an ingredient for a side dish. They believe the plant to be sacred; it is the embodiment of Hāloa, the original ancestor of the Hawaiian people. So when a bowl of poi was offered at meal time, it was believed the spirit of Hāloa was also present.

Natural Reverence

Poi is the first of many examples I encounter of how, in order to get a real understanding of Hawaiian food and culture—and why preserving it is so important to natives—the region’s history and beliefs must also be acknowledged.

Early Hawaiians were a polytheistic and animistic people. They believed in many deities and spirits, some of whom were personified in plants, animals, the earth, waves and sky. The only “religion” during ancient times was a respect and oneness with all things in nature—that in itself was pono, or righteous. There was no concept of a “Supreme Being” or “Creator God,” as that would indicate a separation between humanity and divinity, as is prevalent in Western thought. Prayer was an essential part of early Hawaiian life, whether it was directed to one of the four major gods—Kāne (the god of the sky and creation), Kū (the god of war and male pursuits), Lono (the god of peace, rain and fertility), and Kanaloa (the god of the ocean)—or to lesser deities.

Although many settlers came from Marquesas, Samoa, Tonga, Easter Island and greater Polynesia, it is believed the significant influx of Tahitian settlers brought these beliefs, as well as the system of taboos known as kapu, which imposed a series of restrictions on daily life. The separation of men and women during mealtimes, forbidding women to eat pig, coconut or banana because of their male symbolism, restrictions on gathering and preparing food, and the use of different ovens to cook the food for males and females, are some examples of these prohibitions on early Hawaiian people. The kapu system was overthrown in 1819 by King Kamehameha II, who, at a great lū‘au, sat next to his father’s second wife, an intentional and public violation of the rule forbidding men and women to sit together during meals.

This display destroyed the old religion, but left a void amongst the Hawaiian people. Some abandoned the old gods, while others still worshiped them secretly. When Christian missionaries arrived in 1820 and became integrated in Hawaiian life, many natives converted to Christianity, including the royal family. Although the ancient Hawaiian religion—viewed as paganism—was outlawed and its practices and rituals forbidden, traditions survived in hiding and by practice in rural communities.

Lūʻau

And thankfully they did. Hula, one such outlawed practice, can be observed today throughout Hawai‘i. It is unique to the Hawaiian islands, some legends even specifically suggest its origination on Kaua‘i. Performed by both women and men, hula is a complex art form that utilizes a variety of hand motions to convey the words in songs and chants. These beautiful, fluid dances are commonly performed at a lū‘au, a traditional Hawaiian feast.

But before the entertainment comes the food. Kālua pig, cooked in an underground oven called an imu, is the star attraction. A fire is ignited inside a pit that also contains rocks, which will cook the food—some even placed inside the pig to ensure even cooking. Once they’ve reached maximum heat, the stones are leveled and covered with vegetation—pounded banana tree stumps, banana leaves, and ti leaves—in order to create steam. Multiple layers of green vegetation surround the pig; a material is then placed on top of the entire imu and covered with dirt. After several hours, the cooked meat is unearthed and shredded for the feast.

Other traditional lū‘au foods include chilled lomi-lomi salmon—a dish prepared by massaging the raw, salted, diced fish with fresh tomoatoes and sweet Maui onions—chicken long rice, squid, poke, and Hawaiian sweet potato. For dessert, haupia is a traditional offering. Technically considered a pudding, this lightly sweetened specialty is made from coconut milk, pia (Polynesian arrowroot), or cornstarch and sugar, and cut into block form for service.

A Multi-Cultural Evolution

Today, Hawaiian cuisine has been greatly affected by the many cultures that have immigrated here. You can taste the influence that Japanese, Chinese, Korean, Filipino and Portuguese migrants have had on the islands’ food. Traditional poke seasoning—like scallions, chili peppers, and soy sauce—has been heavily influenced by Asian cuisines. Shave ice, a very popular frozen dessert in Hawai‘i, was brought to the islands by Japanese plantation workers. History shows us example after example of how cultures have adapted. For me, the idea of being from a specific place has shifted—as I’m sure it has for many people who are drawn to new environments, away from the towns in which they were born. The more we travel and explore, the more we appreciate civilizations for what they are.

Ua mau ke ea o ka ʻāina i ka pono is the Hawai‘i state motto—meaning, “The life of the land is perpetuated in righteousness.” The word aloha, though used to say hello and goodbye, actually means love, peace and compassion. It is a guideline on how to live, how to influence others with the love that flows outwards from you. The chaos and noise of the modern world will rumble on. The stress and anxiety and the bombardment on our inner peace will continue. But we can combat that by being mindful. By slowing down and living in the moment, appreciating the small wonders of our world. And by staying connected with our true selves and the planet that has given us so much.

Aloha.

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.