For the first few days, my primary agenda is trying to identify if what I’m smelling is jasmine or honeysuckle. Wafts of a crisp, honeyed perfume tumble out of nowhere, around corners and down alleyways, like silent phantoms able to clear stone walls in one leap.

It’s fitting, really, that there’s such an intoxicating scent in the air. Bassano del Grappa is a town that definitely caters to spirits—but this is no spooky haunting; it’s a hallowed one.

An hour northwest of Venice by train, straddling the Brenta River as it spills from the Venetian Prealps, Bassano sits in a kind of humble fame. It’s just far enough from Italy’s well-trod tourist track that most wouldn’t think to come here. Still more wouldn’t think to come here for a drink, not if the grappa headlining local menus was anything like what they’re remembering (permanent memories of a colorless, lighter fluid-like substance have a way of sobering even the most committed drinker).

But this isn’t a story about what most people do. Few good stories are. This is a story about grappa and why, if you fancy yourself a wine-lover, cocktail-lover, or imbiber of anything divine, you owe it to your glass to give grappa a(nother) go. As long as it’s grappa from Bassano.

What is grappa, exactly? Originally called graspa, the Venetian word for “bunches of grapes,” grappa first emerged as a simple peasants’ drink; farmers resourcefully two-timed wine, fermenting and distilling the leftover grape pomace after pressing the juice. While it’s hard to say who made grappa first, it’s safe to say who has made it the longest. For that, I’m exactly where I need to be: overlooking the Brenta on Bassano’s Ponte Vecchio, steps away from the bar at the Grapperia Nardini.

NARDINI

B.lo Nardini has been making grappa in Bassano since 1779. That’s when founder Bartolo Nardini bought an inn on the east side of the river and started serving grappa at the bar attached. The bar’s convenient location—the last stone doorway before crossing the bridge—made it an easy stop, especially for barge drivers carrying timber logs destined for Venice. Today the inn portion has been renovated and the distilling takes place off site, but the bar itself remains exactly the same. That’s why I’m outside it.

Not that the inside is nothing to see. The bar’s three rooms evoke a strong sense of hearth, sandwiching you between tiled floors and wood-beamed ceilings, with simple white walls lined with grappa bottles and copper cisterns. Antique gilded frescoes even panel the front counter. When my drink is set there, a deep crimson-colored concoction finished with a lemon peel, my hand looks out of place, like it reached into a painting in which it doesn’t belong.

I take my glass and head outside—because I really, really want to belong—and clustered on the bridge, with their own red drinks in hand, are the Bassanese. It’s aperitivo time and there’s no better ambiance for it than right here, right now (locals always know best; these particular locals have gathered here for over two hundred years). I sip my drink. It tastes like a negroni but more grounded and sparkly, just sweet enough on the finish that you go back for more sips. It’s a mezzoemezzo, Nardini’s own creation that uses equal parts of its rosso and rabarbaro liqueurs topped with cold soda water, perfect for settling whatever you’ve eaten that day to make room to eat more. I finish my drink, many sips in short succession. I’m hungry for more Nardini.

On to the grappa, I decide. It’s the reason I’m here. The thing to know about Nardini’s grappa is that, while it may inherently be the same acquavite di vinaccia you’d find elsewhere in Italy, Nardini is obsessive over its distillation. They were among the first to introduce steam distilling and employ a double-distillation of the heart cut to remove any remote trace of oil. Although the pomace used in today’s grappa no longer includes woody grape stems, the wood found in grape seeds can still produce these oils; they’re thought to be the cause of stomach aches when consumed in lesser alcohols.

It’s a difference you can taste even in Nardini’s most straight-forward product, the clear Aquavite aged for one year in stainless steel. As you brace yourself for the impact of fifty percent (also available in forty percent and sixty percent) alcohol, you’re instead kissed with a sweetness comprised of eighty percent red and twenty percent white grape, tasting the pomace in all its fullness. In fact, it’s in drinking this that you realize what alcohol is supposed to be: a concentration of what’s no longer there. Subtle hints at a former life—and one that definitely gets better with age.

Moving up the ranks from Nardini’s Riserva (barrel-aged three to five years) to its fifteenth year, to even a rare fifty-plus year grappa that’s too strong to sell at market, the alcohol content is but an afterthought. Instead, you’re tasting the marriage of Slavonic oak and grape. Sugar notes added by time. The quiet potency of what should have been wine waste but was granted a reprieve. A second chance.

I, for one, want seconds.

THE BOLLE

But there’s more to see and more to drink. So I pace myself.

Nardini’s impressive history has remained family-owned and operated for seven generations; the sense of stewardship and commitment to Bassano is evident. The Palladio-designed Ponte Vecchio is both a centerpiece of the town and the Nardini label, but as the family prides itself on preserving (albeit fermenting and distilling) its past, it’s not clinging so tightly that it can’t envision the future.

It’s why in 2004 on its 225th anniversary, Nardini unveiled the Bolle. Housing their research lab and a mixed use public events space, the Bolle is located on the current distillery’s grounds about a ten-minute drive from the bridge. It’s a dramatic structure: two circular glass orbs suspended over a shallow pool of water. They’re connected by a glass stairway that descends seven meters deep, revealing angular cement walls and red furniture appearing to glow. A mix of skylights, floor lights and overhead spot lighting is to thank for keeping the feel, very Bond villain-esque, impossibly spacious and calm.

Designed by another famed architect, Massimiliano Fuksas, the Bolle is meant to reflect the alchemy of grappa—the two orbs as two fresh drops coming off the still, while the building’s many diagonal lines mimic distillation’s evaporation. But the structure actually goes beyond that. The Bolle isn’t just Nardini’s way of securing architectural relevance 225 years from now, it’s a demonstration of a cross-generational synergy that’s becoming rarer to find. Yes, business thrives on progress and evolution, but there’s a way to achieve a global presence without retiring the history that got you there. Age respects tradition just as much as it seeks innovation.

Nardini proves, from bridge to Bolle, you don’t have to forsake craft to embrace change. Once you achieve the right blend of both, you’ll have something perpetually delicious.

There’s someone else I go and see about this.

CAPOVILLA

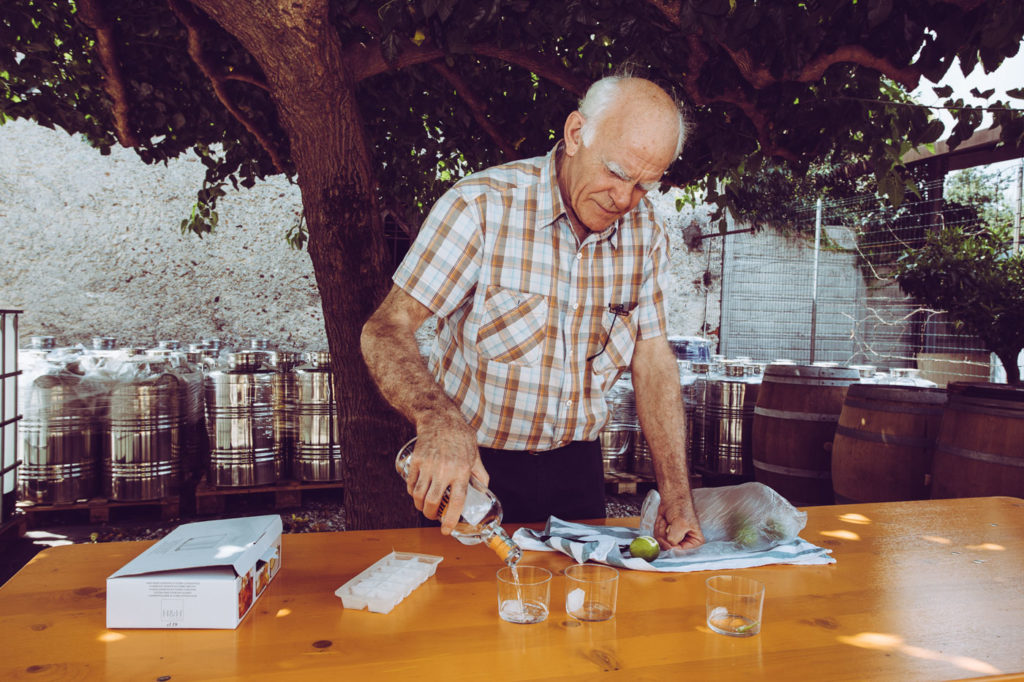

His is a restored farmhouse on the outskirts of Bassano. It’s quiet here, with maybe an occasional rooster or cat scuttling across your path. There isn’t a welcome center or even a welcome sign. On the day I visit, I’m greeted by pallets of shiny steel vats in the courtyard.

He’s the new guy. Vittorio “Gianni” Capovilla doesn’t come from a long line of distillers. His labels don’t date back to the Revolutionary War. He’s only been doing this for a mere thirty years, since the time his passion for distilling eclipsed a career selling wine-making machinery.

In addition to making rum on a Caribbean island, Capovilla makes grappa. Here. More specifically, he makes fruit distillates, grape pomace is just one of over forty varieties ranging from apricot to cherry, pear to apple. Everything he can, he grows on his property. Sensing when the fruit is ripe, he ferments it naturally with its own native yeasts before distilling and leaving to rest in either wood or stainless steel—for four years. Just prior to bottling, he cold filters the distillate through a machine of his own design to collect any remaining methanol and cuts it down with water.

The final product is striking.

His grappas, of which I try several, all use clean organic grapes primarily from northern Italy. The glass isn’t even to my lips before I’m smelling it—a traminer from Bolzano—and it’s down just as fast. Not because I shoot it, but because the liquid is so velvety smooth my mouth can’t hold onto it, even at forty-one percent alcohol.

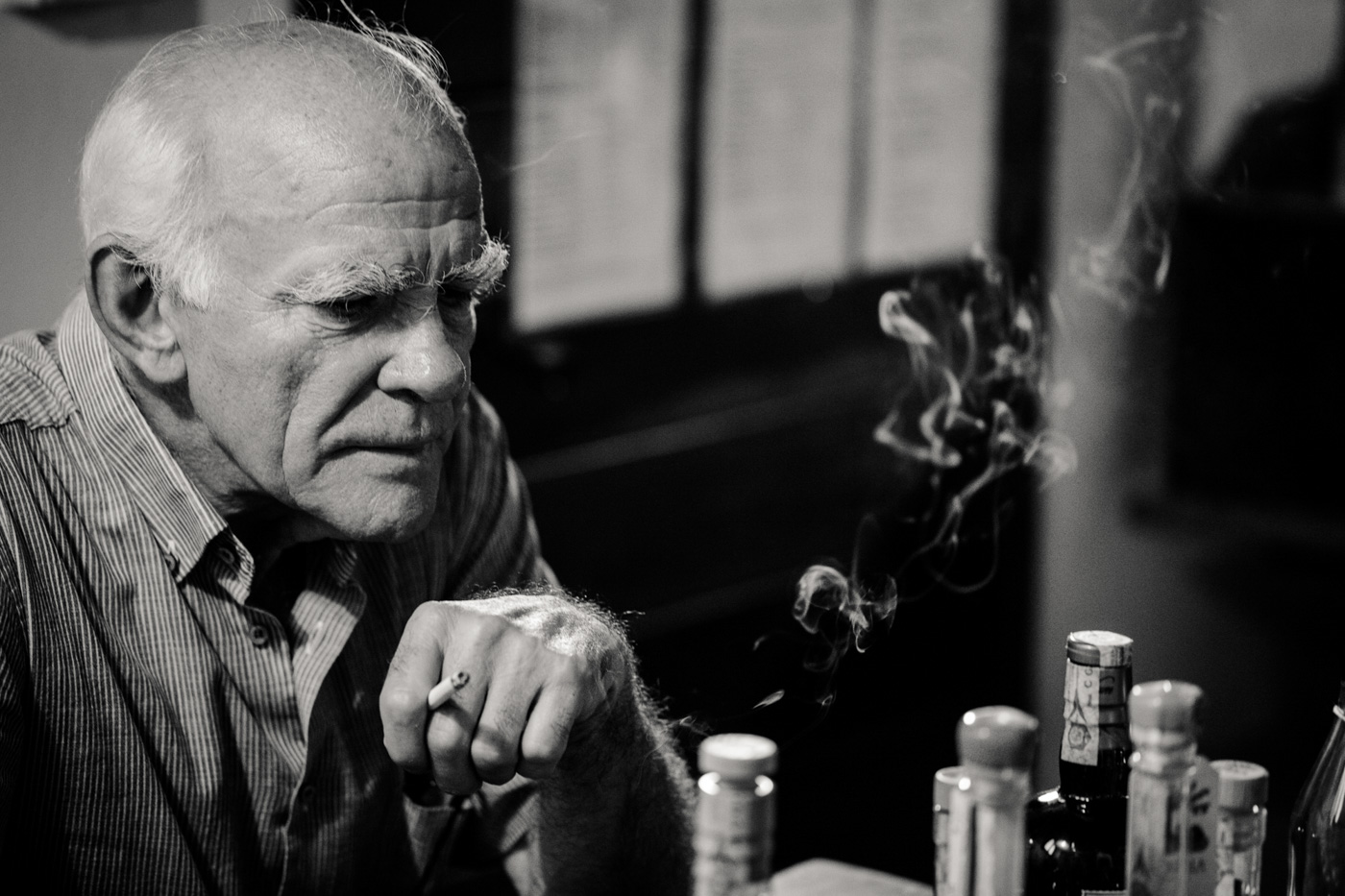

Leading me from fermentation room to distillation floor feels akin to being welcomed into Capovilla’s private home, granting meaning to every coil as a collector would to his well-chosen art. In the courtyard he opens up a vat, warm from the sun, and dips in a finger. He motions for me to do the same. It’s a white raspberry appetizer, liquefied into pure essence on the tip of my index.

In the bottling room he explains how every distillate has its own color of wax. Each bottle is hand-filled, hand-tied, hand-dipped and finished with a handwritten label (for reference, he produces forty to fifty thousand bottles a year). My shock at this, shockingly, almost doesn’t seem to register. Why do it any other way? Why strategize or industrialize when the process brings such joy as it is?

I get the sense that’s what he’d tell me, if I spoke better Italian and he spoke more English. The truth of it hangs in the air regardless, mixed with his cigarette smoke.

It’s a radically different spirit here—that’s my eventual takeaway. It’s progress of a different kind, one that’s ahead because, simply, it isn’t looking there. The focus is on making something excellent and in its excellence the passion secures its future. I say it about Capovilla, but also about Nardini and Bassano too.

Surprisingly, Bassano del Grappa wasn’t named after the drink, but in homage to soldiers who fought and died on Monte Grappa during WWI. I find that even more suitable—to honor life. What better way than with an eau de vie.

——

Author’s Note: Astute Bassano visitors and grappa fans will note there is third distillery absent from this piece, Poli. Operating in Bassano since 1898, Poli certainly adds to the level of remarkable aged grappas available in town. Due to an unexpected scheduling conflict at the distillery, I was not able to visit and interview in the timeframe required. Even still, their Cleopatra Amarone Oro is worth an honorable mention. And a taste.

Our comments section is for members only.

Join today to gain exclusive access.